I was scheduled for my private pilot checkride and everything was set. The paperwork was in order, my instructor had signed everything he needed to sign and the cleanest plane on the line had been reserved. I got myself to the airport two hours early just in case, via the most circuitous means imaginable, beginning with a New Jersey Transit bus through the Lincoln Tunnel and ending with a sprint across four lanes of high-speed traffic and a mile-long walk along an unpaved, mole-tunneled, grassy shoulder to the Caldwell, N.J., airport. A journey of 15 miles as the crow flies takes the better part of two hours. Who said air travel was expedient?

I was scheduled for my private pilot checkride and everything was set. The paperwork was in order, my instructor had signed everything he needed to sign and the cleanest plane on the line had been reserved. I got myself to the airport two hours early just in case, via the most circuitous means imaginable, beginning with a New Jersey Transit bus through the Lincoln Tunnel and ending with a sprint across four lanes of high-speed traffic and a mile-long walk along an unpaved, mole-tunneled, grassy shoulder to the Caldwell, N.J., airport. A journey of 15 miles as the crow flies takes the better part of two hours. Who said air travel was expedient?

Shouldn’t I Have Done This The Night Before?

Nevertheless, I’m early, I’m ready and I’m thinking about shooting a few takeoffs and landings to calm my nerves before departing for Somerset Airport to meet my fate and the designated executioner (DE), err, examiner. But first, I need to check the logbooks for the aircraft I have scheduled. Everything is looking good, but wait: don’t transponders need to be checked every 24 months? If I can’t show the DE that the entry was made, then I can’t prove the plane is airworthy and then I can’t do the checkride and — ohmigod — I need to find the previous logbook. Where the heck is it and where is the A&P? He’s gotta help me find it … and shouldn’t I have done this the night before?

Nevertheless, I’m early, I’m ready and I’m thinking about shooting a few takeoffs and landings to calm my nerves before departing for Somerset Airport to meet my fate and the designated executioner (DE), err, examiner. But first, I need to check the logbooks for the aircraft I have scheduled. Everything is looking good, but wait: don’t transponders need to be checked every 24 months? If I can’t show the DE that the entry was made, then I can’t prove the plane is airworthy and then I can’t do the checkride and — ohmigod — I need to find the previous logbook. Where the heck is it and where is the A&P? He’s gotta help me find it … and shouldn’t I have done this the night before?

No problem; I’ve still got an hour before I need to leave.

Two hours later, I’m preflighting another plane, one with proper paperwork, and freaking out.

I Should Have Punted

I hastily depart, and arrive for my PPL checkride almost exactly two hours late. What’s that expression about first impressions? Nerves shot, I convince the DE that he really wants to go through with this and that I’m ready. How embarrassing would it be to show up at work tomorrow, everyone asking me how it went? I’d to have to explain how I couldn’t take the test because I couldn’t even get the paperwork straightened out. No, I want to do this right now. Hindsight being 20-20, I now know I should have punted and come back to fight another day.

Thankfully, the oral exam goes well; I’d been cramming for it. With that out of the way, it’s on to the practical test.

Thankfully, the oral exam goes well; I’d been cramming for it. With that out of the way, it’s on to the practical test.

Preflight complete and additional questions answered, we take off. Of course, the DE drops his pen during the takeoff, obviously a thinly-veiled ploy to "distract" me. I take it in stride and keep flying the airplane, then — at a safe altitude — I help locate the pen, feeling like Captain Al Haynes for about two seconds and then riddled with fear once again. I’m afraid the DE is still annoyed with me for being late and — ohmigod — I can’t deal with failing this test. What happens then? I’ll have to take the test over! Isn’t there a pink slip or something — I mean, how embarrassing is that?

As these thoughts are scurrying through what’s left of my mind, here comes and there goes my planned cruise altitude; caught that one just in time. So far I’ve managed to keep the aircraft skating a razor’s edge between the boundaries of the PTS, but there’s more to come. My nerves can’t take too much more of this.

So Far, So Good…

We fly the initial leg of the planned cross-country, eventually breaking it off for maneuvers and hood work. Somewhere in the back of my head I know that I have performed everything to this point within limits, and can confidently stride into the office tomorrow wearing the white scarf and aviator goggles I have purchased for the occasion. Again my nerves settle, if only briefly. Simulated-instrument tasks completed, I remove the view-limiting device and I now realize the man next to me is either some kind of genius or simply a madman; after spending the last 10 minutes in one turn after another, staring at nothing but whirling dials and digits, and still queasy from the unusual attitude recoveries, he says, "Take me to the nearest airport."

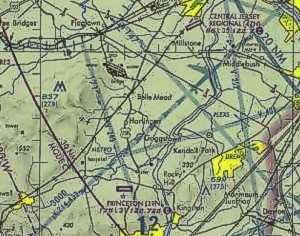

I begin to attempt to quantify just how much of an idiot I am for arranging a flight test with this man, to be conducted in an area different from my local practice area. Short of anything more specific than "3,500 feet above New Jersey," I have no idea where we are, but my training has at least given me a decent aptitude for VOR use. I tune, identify and quickly fix my position. I locate the Princeton, N.J., airport; "There’s Princeton Airport," I say, not at all convincingly. "Okay, take me there and show me a short-field landing," intones the genius/madman in the right seat.

Now, I’ve always hated short-field landings, and I’m still sweating bullets from all of the preceding events, but I comply with his wishes because, after all, he’s running this show. We’re a bit high, having just been doing airwork, so I do some 360-degree spirals to lose altitude (at this point you should get out your New York Sectional if you have one).

Here’s another thing I’ve always hated: letting the runway get out of sight once you have acquired it. But alas, I’m too high, and must descend. So, about five miles north of Princeton, I reduce power and commence a series of descending spirals. Eventually, we arrive at an altitude suitable for entry into the traffic pattern and I frantically scan the horizon for the airport. Recognizing what appears to be a runway, I head for it like a moth to a porch light. I look at my kneeboard, scouring the info I had written down at 5:00 a.m. that morning, review the CTAF frequency and the pattern altitude and, for some reason, I note that there are car rentals available here. Announcing my approach, pattern entry and lining up on downwind, I hear no complaints; no one else is in the pattern. Glancing at the runway threshold, I see the number 25. Hmmm, that’s odd. My kneeboard says Princeton’s runway is aligned 10-28, not 7-25.

Here’s another thing I’ve always hated: letting the runway get out of sight once you have acquired it. But alas, I’m too high, and must descend. So, about five miles north of Princeton, I reduce power and commence a series of descending spirals. Eventually, we arrive at an altitude suitable for entry into the traffic pattern and I frantically scan the horizon for the airport. Recognizing what appears to be a runway, I head for it like a moth to a porch light. I look at my kneeboard, scouring the info I had written down at 5:00 a.m. that morning, review the CTAF frequency and the pattern altitude and, for some reason, I note that there are car rentals available here. Announcing my approach, pattern entry and lining up on downwind, I hear no complaints; no one else is in the pattern. Glancing at the runway threshold, I see the number 25. Hmmm, that’s odd. My kneeboard says Princeton’s runway is aligned 10-28, not 7-25.

Huh?

Again looking abeam the threshold, the runway number still stubbornly appears to be composed of the numerals 2 and 5. I conclude I must have written the number down wrong during my preflight planning. A glance to my right shows a perfectly content DE, arms folded across his chest; he seems to be having a good time.

I continue the approach. Turning base, I call on the CTAF. Turning final, I call again. I execute a lousy short-field landing and turn off at the second taxiway (the runway distance used should indicate just how bad it was). I perform my after-landing checklist because one of the items on the PTS is how well you use checklists — no worries there, I do that quite well.

Of course, I used the checklist because I can’t remember a thing at this point and my nerves are shot. I think I just blew the checkride because that was the first thing I really didn’t do within the PTS and — ohmigod — how can I tell anyone I failed the test?

What Next?

I turn to the DE, who ominously still has his arms folded across his chest, and say, "Well, what do you want me to do next?"

He says, "Well, first off, I’d like you to tell me what airport we’re at."

With my heart now firmly planted in the pit of my stomach, I immediately know what I did wrong, and I want to get out of the plane, engine running, and lie down on the runway for the next arrival: I had just executed a lousy short-field landing at Central Jersey Regional Airport, 10 miles north of the airport at which I was supposed to land.

With my heart now firmly planted in the pit of my stomach, I immediately know what I did wrong, and I want to get out of the plane, engine running, and lie down on the runway for the next arrival: I had just executed a lousy short-field landing at Central Jersey Regional Airport, 10 miles north of the airport at which I was supposed to land.

Perhaps mercifully, the DE clears up any confusion and tells me that I have in fact failed my checkride. I want to go home; I could walk from here. It would only take a few hours at a good clip. He tells me to taxi to the departure end of the runway and show him a short-field takeoff. I comply, because I now figure I have nothing to lose. I nail the takeoff and proceed to fly the remaining tasks with aplomb, including those ground reference maneuvers that gave me fits all through my training. Isn’t it interesting how — with nothing to lose — I can perform the remaining tasks without a problem?

After landing back at Somerset, the DE writes out a nice letter to my instructor (who was taught by this same man to fly a few years back). It reads: "Rob did a fine job — other than landing at the wrong airport. Go easy on him."

That letter is still in my possession. I will never forget that day, that man or that sequence of events.

Aftermath

So, I failed. I did one of the dumbest things a pilot can do. But I selected the day of my PPL checkride to have that lapse in judgment, and I feel it’s because I let peripheral concerns like passing and failing get in my head while I should have been flying the aircraft.

My retest was with the same guy. He felt that since the rest of the flight test went so well, I only needed to demonstrate "VFR nav proficiency."

Well, guess what? The visibility on the retest day was three miles in haze. You’d think I’d catch a break. My instructor had to fly with me to the DE’s airport, because the FBO wouldn’t let me take the plane out solo in those conditions. But with the DE as a passenger, I poked my way through the haze, correctly identified some landmarks and airports and managed an okay short-field landing to boot. At last I had secured the Private Pilot Certificate.

Lessons Learned

You would not believe the number of people who have done what I did, sometimes mistaking large, tower-controlled fields for the small airport they were aiming for. You only find this out when you tell a pilot you have landed at the wrong airport before, that you are a member of the fraternity. I am a member, so I am privy to this exotic information. We do not wear jackets emblazoned with membership insignia, so it takes time to ferret out all the members at your local airport. Be patient, the stories are wildly entertaining.

Everyone has their list of lessons learned from the Private Pilot checkride. Here’s mine:

Everyone has their list of lessons learned from the Private Pilot checkride. Here’s mine:

Your DG should concur with the rest of the approach plan. I had in fact located Princeton airport that day, but after descending I desperately searched the horizon for a runway, any runway. Unfortunately for me, the first runway I spotted was five miles north of my position, not five miles south, where Princeton was waiting for me. Had I backed up what I saw out the window with a glance at the DG and the chart, I would have known to simply keep turning another 180 degrees.

Relax. Your CFI will not send you on your way to meet a Designated Examiner until he or she is confident you are more than ready to pass the test. Remember, especially at a Part 61 school, that the CFI has almost as much at stake as you do. Relax.

Trust your preflight planning, assuming you’ve done any. Had I trusted my kneeboard, I would have known on downwind I was not in the right place, and could have broken off the approach.

Local knowledge is a good thing; especially on a checkride, when you have a lot of other things on your mind such as how good you will look strolling in to the office the next day, wearing your white scarf and clutching your temporary airman’s certificate.

I own a GPS now and I’m surer than ever the airport I’m landing at is the one I’m supposed to be landing at.

Lastly, fly the aircraft! Do not let distractions enter your mind before or during your checkride. Nervousness is all well and good, but assuming you’re concentrating on the task at hand, that should all disappear when you yell "clear prop."

Take it from me, if you’re still thinking about white scarves and aviator goggles during the unusual-attitude recovery, your head is in the wrong place.