This was a trip I had been anticipating eagerly allyear. I’d been invited to give a seminar at the CaymanIslands’ International Aviation Week gathering, and would be flying myT310R from its west coast base to Key West Florida, then joining up with The Cayman Caravan to fly over the top of Cubaand into Grand Cayman.

This was a trip I had been anticipating eagerly allyear. I’d been invited to give a seminar at the CaymanIslands’ International Aviation Week gathering, and would be flying myT310R from its west coast base to Key West Florida, then joining up with The Cayman Caravan to fly over the top of Cubaand into Grand Cayman.

Whenever I make a coast-to-coast trip in the 310,I try to work as many productive stops into the itinerary as possible. Thistrip was no exception: I’d be spending a day in Phoenix, Arizona, for a businessmeeting on the way out, going to the Caymans for a week, spending a weekin Boca Raton, Florida, at AVweb headquarters, and then stopping atthe Cessna single-engine plant in Independence,Kansas, on the way back to California. It was an ambitious schedule, butdoable…if nothing went wrong.

Trip Preparations

In anticipation of the trip (which would involve around 30 hours of flyingtime), I’d elected to do an earlier-than-usual oil and filter change so thatno scheduled maintenance would be required during the trip. I also sent inan oil sample for SOAP analysis, and the report from Engine Oil Analysiscame back clean.

I’d also made a point of sending my ailing Stormscope in to BFGoodrich forrepair a month and a half before the trip, knowing that there were boundto be plenty of TRWs to circumnavigate in the Deep South in June. The blackboxes came back about two weeks before my departure (with a $500 repair bill).Unfortunately, upon reinstalling them in the airplane and strapping on atest set, it appeared that the Stormscope computer was just as sick as whenI’d sent it in. By a stroke of luck and ingenuity, Tom Rogers at AvionicsWest managed to come up with a loaner WX-10 computer module that I couldtake on the trip, while mine got shipped back to BFG with a nastygram.

I’d also made a point of sending my ailing Stormscope in to BFGoodrich forrepair a month and a half before the trip, knowing that there were boundto be plenty of TRWs to circumnavigate in the Deep South in June. The blackboxes came back about two weeks before my departure (with a $500 repair bill).Unfortunately, upon reinstalling them in the airplane and strapping on atest set, it appeared that the Stormscope computer was just as sick as whenI’d sent it in. By a stroke of luck and ingenuity, Tom Rogers at AvionicsWest managed to come up with a loaner WX-10 computer module that I couldtake on the trip, while mine got shipped back to BFG with a nastygram.

Off to a Flying Start

Departure Saturday finally arrived, and I launched on-schedule from SantaMaria. My first stop was Palomar Airport in Carlsbad, California, to pickup my friend Joe Godfrey who would be copilot on this trip. As a veteranof numerous solo transcontinental trips by lightplane, I can tell you thathaving a second pilot along makes the trip a lot more fun and a lot lessexhausting. So I invited Joe along to the Caymans, and he thought about itfor about four milliseconds before saying yes.

An experienced instrument pilot and owner of a beautiful Bellanca Super Viking,Joe would be accompanying me on the trip across the country, down to theCaymans and back to Florida…at which point he would be taking a commercialflight back while I did my business in Boca Raton. My return to the westcoast would have to be flown solo.

The plane performed flawlessly during the hour-long hop to Palomar, and Ieven shot an autopilot-coupled ILS approach through the overcast. Joe waswaiting for me. We loaded his luggage – even found room for his golf clubs- and launched IFR for Phoenix. I asked Joe if he’d like to take the leftseat for this leg, and this time he took only two milliseconds to say yes.

The flight to Phoenix was beautiful and uneventful, and we landed at SkyHarbor Airport just in time to make our dinner date with friends. CutterFlying Service had our rental car waiting planeside before the props cameto a stop.

I decided all the omens pointed to a perfect problem-free trip to the CaymanIslands and back. But then, I was never very good at reading omens.

Eastbound…

After a very productive Sunday in Phoenix, Joe and I headed for the airportearly Monday morning to launch for points east. We probably should have seenthe changing of the tea leaves when we found ourselves mired in citytraffic…our 15-minute drive to the airport wound up taking nearly an hour.

The Weather Channel and the DTN weather machine at Cutter seemed to agreethat we’d have smooth sailing across Arizona, New Mexico, and most of Texas.Things were forecast to start getting sticky in southeast Texas and Louisiana,however.

We needed to arrive in Key West no later than early afternoon on Tuesday.So we decided to file from Phoenix to Austin, Texas (a four-hour leg), andthen try (weather permitting) to fly one more short leg to some suitableR.O.N. in Louisiana, Alabama, or the Florida panhandle, thereby putting uswithin easy one-leg range of Key West by Monday night and letting us traversethe Florida thunderstorm belt in the early morning. It was a good plan.

The computer said we could trim nearly a half-hour off our flying time toAustin by climbing up to the Flight Levels, a prospect that excited Joe becausehe’d never flown that high in a piston aircraft. We filed for FL190. I decidedto fill all five tanks, even though the avgas was pricey at PHX, to giveus as many options as possible. This proved to be a good decision.

It was hot as Hades by the time we lifted off from PHX, tolerable by thetime we climbed through ten thousand, and chilly enough by the time we reachedFL190 that we had to flip on the cabin heater. The trip across AZ and NMwas smooth and spectacular, and by the time we crossed over El Paso it wasclear that we were making exceptionally good time. So good that we startedtalking about the possibility of pressing on past Austin.

Both Joe and I are lovers of Cajun food, and Joe’d received a tip that someof the best could be had at Lafayette, Louisiana. Our calculations showedthat at our present rate, we should be able to make it non-stop to Lafayettewith about 1+15 worth of fuel left over. We also calculated that Lafayettewas easily within one-leg striking distance of Key West. An R.O.N. at Lafayettesounded like a winner, so we advised Houston Center that we were amendingour destination to LFT.

As we got “east of the Pecos”, activity started to kick up on our Stormscope.Flight Watch advised that there was an area of rapidly-building convectiveactivity just northeast of Houston, but that so far it seemed to be southof our route. Scattered clouds beneath us thickened up to broken and thenovercast. As we passed north of Houston, we could see what looked like monstercumulus out the right window, and decided we were glad not to be any closerto it. (Later on the TV news, we learned this particular thunderstorm droppedgolfball-sized hail.)

Glitch Number One

The GPS said we were only a half-hour out from LFT,so we asked to start down from FL190. I flipped altitude-hold off and rolledthe autopilot pitch wheel forward to 1,000 FPM down. Not long after that,Joe heard something in his headset that sounded like me saying “OH SHOOT!!!”or words to that effect.

The GPS said we were only a half-hour out from LFT,so we asked to start down from FL190. I flipped altitude-hold off and rolledthe autopilot pitch wheel forward to 1,000 FPM down. Not long after that,Joe heard something in his headset that sounded like me saying “OH SHOOT!!!”or words to that effect.

“What’s wrong?” asked Joe, frantically scanning the unfamiliar twin Cessnainstrument panel.

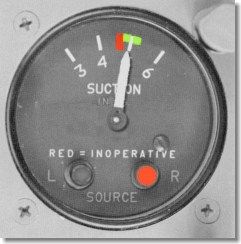

“See that little fluorescent orange button?” I replied, pointing to the vacuumgauge. “We’ve lost our right vacuum pump.” Visions of dollar-signs floodedmy brain, making it hard to concentrate on flying the airplane.

Technically, I explained to Joe, loss of a vacuum pump might conceivablybe considered a no-go item under FAR 91.213. Practically, I didn’t feel greatabout flying to the Caymans with only one pump.

Once on the ground at Lafayette, I checked my wristwatch: 6:30 pm CDT. Toolate to find any maintenance personnel here, but still business hours backon the west coast. We decided to phone Chief Aircraft in Oregon or San-ValDiscount in California and see if we could get them to overnight a replacementpump to our hotel in Key West, where it’d hopefully be waiting for us whenwe arrived the next day. That way, we could stay on schedule for the CaymanCaravan but still have the pump fixed before our flight to the Caymans. Soundedlike a plan. But we’d have to act fast.

The first order of business was to determine the correct part number of thefailed vacuum pump. I was pretty sure that it was an Airborne 442-CWbut what if I was wrong and it was a 441-CC?

Lesson #1: Bring your maintenance logs and your parts and service manualsalong on any long trip.

Lacking any documentation, Joe and I decided to decowl the right engine onthe ramp and have a quick look at the failed pump. Sure enough, the partnumber tag was legible, it was a 442-CW (an eight-year-old RAPCO rebuilt),and it was definitely dead: I could see the sheared coupling when Joe rotatedthe prop.

Next, we needed the phone number for Chief or San-Val. Surely someone atthe FBO has a copy of Trade-A-Plane somewhere? Nope!

Joe tried calling directory assistance at 1-800-555-1212 to get the numbers.The operator insisted that there was no listing for Chief Aircraft in GrantsPass, Oregon! Joe did get a number for San-Val, however.

Lesson #2: Always carry a copy of Trade-A-Plane (or a little blackbook of key phone numbers) on any long trip.

We called San-Val. They didn’t have a 442-CW pump in stock, but they didhave a 400-series pump repair kit consisting of a new hub, new vanes anda new coupler for $135. Could they overnight it to Key West? Yes, if theyhurried. Do it!

Satisfied that we’d done all we could do for the moment, Joe and I talkedthe nice folks at Paul Fournet Air Service into lending us their courtesycar for the night and giving us directions to the best Cajun restaurant inLafayette, where we gorged ourselves with gumbo, alligator fritters, anda variety of other bayou delicacies that I can’t remember how to spell, allthe while being entertained with live Cajun music. It was enough to makeus forget the $2.50/gallon price for 100LL!

After dinner, we checked into the Holiday Inn Express adjacent to the airport,and I fell dead asleep within minutes. Great food will do that to you.

Off To Key West…

I awoke early Tuesday morning, tuned in The Weather Channel, fired up mynotebook computer, and started planning the morning’s flight to Key West.

There was bad news and good news. The bad news was that Florida was awashin thunderstorms already, some of which looked like they might be too denselypacked to pick through. The good news was that Louisiana was the jumping-offpoint for an overwater Jet Route over the Gulf of Mexico that could takeus to Key West while remaining clear of most of the convective activity,and would shave 45 minutes off the flying time as a bonus. We’d even havetailwinds if we flew up high. Sounded like a plan. I filed J58 and J41 atFL190.

The flight to Key West was textbook perfect, except for that fluorescentorange ball that kept staring at me from the vacuum gauge. The engines ransmooth as silk despite the overwater routing, and the dual moving-map GPSswe were carrying made navigation a breeze. On one occasion, we asked to deviatenorth around a little build-up and Center approved it with the proviso thatwe remain within 4 NM of the J58 centerline. GPS made this easy.

The overwater route kept us relatively clear of the weather until the last20 minutes of the flight. Key West weather was good, but there was a lotof TRW activity to the north and east. We heard many EYW-bound flights fromthe Florida mainland giving up and landing short of the destination. Ouroverwater approach didn’t look too bad, and we picked our way through usingthe Stormscope, encountering some moderate rain during our descent from FL190but no real turbulence.

We landed at Key West around 1:30 pm EDT, secured the aircraft, caught ashuttle bus to our hotel and checked in at the front desk. Had an overnightexpress package arrived for us from California? Yesssss!!!!! Don’t you justlove it when a plan comes together?

Vacuum Pump Surgery

I pulled out my pocket knife and cut open the little package from San-Valright on the spot. The good news was that it appeared to contain a 400-seriespump repair kit, as ordered. The bad news was that the kit did not containeither an accessory pad gasket or a band gasket, so if we damaged eithergasket while removing and disassembling the failed pump, the game would belost.

Joe and I hopped a shuttle bus back to the airport with the pump kit in-hand.By now it was 3:00 pm. We decowled the right engine and surveyed the little travelling toolkit that I always carry in theleft wing locker of the 310. We decided that the only critical tool we weremissing was a 7/16″ offset wrench, needed to loosen and tighten the fournuts that secure the vacuum pump to the engine accessory pad. Joe turnedon his charm and managed to sweet-talk one of the local A&Ps into lendingus a 7/16″ Snap-On offset wrench for a few minutes.

Lesson #3: Always carry a good collection of tools with you, and be preparedto grovel for what you need but don’t have. (I’m adding a 7/16″ offset wrenchto my kit.)

The vacuum and pressure hoses came off easily (remarkable after 8 years ofbaking) and the pump came cleanly off the accessory pad, leaving the padgasket totally intact and undamaged on the engine. All that clean livingwas finally paying off!

We took the pump, the repair kit and a few tools up to a little kitchen areaabove the FBO and managed to remove the back cover of the pump without cuttingthe band gasket. The graphite hub had fractured into a half-dozen pieces,and the vanes had exploded into a couple of dozen more pieces. Classiccatastrophic dry vacuum pump failure. After 8 years and nearly 1,000 hoursof service, I figured that RAPCO rebuilt pump was fully depreciated.

After making careful notes of the order in which the parts came out of thepump and which direction the rotor was oriented, I dumped all the graphitefragments into the trash can and cleaned up the pump cavity as well as possible,using air and paper towels. (I didn’t dare use solvent since liquids aredeath on dry vacuum pumps.) Joe and I then installed the new hub and vanesfrom the repair kit, reassembled the other pump parts, and carefully reinstalledthe band gasket and back cover.

My pocket knife turned out to be the optimal tool for extracting the shearedcoupler from the front of the pump. The new coupler from the repair kit thenwent in easily. The pump passed the rotate-by-hand test and was ready toreinstall on the engine.

Reinstallation turned out to be the most difficult part, because gettingthe 7/16″ nuts threaded onto the attach studs in the confines of the pumppockets turns out to be tricky. After dropping several nuts and wasting agood deal of time searching for them, Joe and I improvised a nut starterby wrapping a flat screwdriver blade with duct tape (sticky side out) andmanaged to get all the nuts threaded in place.

The pump passed the rotate-the-prop-by-hand test, then theturn-over-the-engine-with-the-starter test. So we cowled up the right engineand I started it. Lo and behold, the repaired pump produced the requisite5 in. hg. of vacuum on the gauge and the gyros erected. Success!

The entire remove-repair-reinstall process took only about an hour, and Iwas a happy camper. I’d always heard bad things about do-it-yourself vacuumpump repair kits, but decided that if the repaired pump lasted just fourhours (to the Caymans and back to Florida), I’d be happy. Anything more wouldbe gravy.

Back at the hotel in Key West, we joined our fellow Cayman Caravaners fordinner and got our briefing for the over-Cuba flight to Grand Cayman in themorning.

Hello, Havana Center…

Wednesday morning, we were back at the Key West airport for our flight toGrand Cayman. The Cayman Caravan is organized to launch groups of four aircraftevery 15 minutes. Our group included a Navajo, a Commanche, an Arrow andourselves (the lone Cessna in a Piper-dominated group). We launched on scheduleat 10:00 a.m. EDT, picked up our IFR clearance from Navy Key West Departure,were handed off to Miami Center, and cleared direct TADPO, flight-plannedroute, maintain 12,000′.

Trimmed and leaned for cruise, autopilot engaged, altitude hold and nav trackingon, dual GPSs mapping our progress toward Cuba. Miami handed us off to HavanaCenter, whose English was surprisingly good. (Somehow, Joe and I were expectingthe Cuban controller to sound like Ricky Ricardo saying, “Lucy, jou’ve gota lot of ‘splainin’ to do!”)

Glitch Number Two

About the same time we spotted the Cuban mainlandin the distance, Joe and I also noticed that we were starting to divergefrom our course line on both GPS moving maps. It didn’t take long to figureout what was wrong: the attitude gyro had spilled about 30 degrees from thehorizontal, and the autopilot was trying to fly the tumbled gyro.

About the same time we spotted the Cuban mainlandin the distance, Joe and I also noticed that we were starting to divergefrom our course line on both GPS moving maps. It didn’t take long to figureout what was wrong: the attitude gyro had spilled about 30 degrees from thehorizontal, and the autopilot was trying to fly the tumbled gyro.

Vacuum failure? No, the vacuum gauge was still in the green and both orangebuttons were pulled in, indicating that both pumps were functioning fine.And the HSI (which uses a vacuum-driven heading gyro) was also working justfine. Looked like a failed attitude gyro. Oh, great!

I disengaged the autopilot and started hand-flying the aircraft, turningback to intercept the airway. Flying over Cuba seemed like the wrong placeto get too far off course. I found the tilted horizon incredibly distractingand finally covered it up with a Post-It Note.

Meantime, I started assessing the seriousness of the problem. The weatherto the Caymans was supposed to be good VFR, so no problem continuing theflight. Odds were that the return trip to Key West would also be VFR. Butthen Joe was scheduled to jump ship at Miami and I’d be flying the rest ofthe way to the west coast solo. Was I prepared to tackle that without attitudeindicator or autopilot? No, I didn’t think so. I resolved to have the AIlooked at during the week I’d be spending in Boca Raton.

I periodically peeked at the AI under the Post-It Note as the flight progressedto see how it was doing. It managed to correct from a 30º tilt to a15º tilt but that seemed to be about the best it could manage. I coveredit back up and continued to hand-fly the airplane.

After a bit less than two hours, we arrived at Grand Cayman, which miraculouslypopped up in the middle of the Caribbean right where the GPSs said it wouldbe. (Lucky thing, too…if we missed it, the next land on that course wasVenzuela!) As I turned short final, I noticed that the attitude indicatorwas finally perfectly aligned with the natural horizon. Big help!

The ensuing week in the Cayman Islands was absolutely fabulous, but thatstory will have to wait for another article. Suffice it to say that themalfunctioning gyro didn’t come up in conversation even once during Caymansweek.

Welcome to Florida…

The week passed much too quickly, and Tuesday morning we were out at theairplane ready to depart for the mainland. Our plan was to fly back to KeyWest to clear U.S. customs and return our rented raft and lifejackets, thenfly to Miami International to drop Joe at his airline connection, and finallyhop over to Boca Raton where I’d be spending the next week on business.

It was Joe’s leg to fly, with me handling nav and comm duties. On takeofffrom Grand Cayman, the attitude indicator initially appeared to be malfunctioning(no surprise there), but shortly thereafter it erected properly and seemedto be behaving. Joe elected to hand-fly the airplane anyway, rather thantrust the suspect gyro by engaging the autopilot. We left the instrumentuncovered and it continued to stay aligned.

We breezed through customs at Key West (they seem to like the Caravan folks)and launched for Miami with me in the left seat. Again, the attitude gyroseemed to be well-behaved (and our field-repaired vacuum pump was still hangingin there, too), so I tried the autopilot and it behaved perfectly as well.

We landed at MIA and Joe sped off in the Signature shuttle van to catch hisairline flight. I reluctantly purchased 40 gallons of $3.00/gallon avgasrather than pay Signature’s $35.00 ramp fee (grrr!), and departed with aVFR clearance moments before a big thunderstorm reached the airport. Welcometo Florida! Fifteen minutes later, I was on the ground at Boca Raton. Onceagain, the attitude gyro appeared to work flawlessly.

Fix It…or Ignore It?

That evening, I debated with myself whether or not to pull the gyro and sendit to the instrument shop. It had worked fine from Grand Cayman to Key Westto Miami to Boca Raton. But somehow I didn’t trust it anymore, and Murphy’sLaw dictated that the next time it failed would be at the most inopportunemoment possible. In the end, I decided to yank the instrument, which I didthe next morning (without even having to borrow any tools) and courieredit off to the J. D. Chapdelaine instrument shop at Fort Lauderdale Executive.

That turned out to be a good decision. JDC’s technician reported that hecouldn’t get the AI to spin up at all when he applied 2.5″ of vacuum, andthat it would just barely spin with a full 5″ of vacuum. The gyro spindlebearings were definitely in very bad shape. I thought back and realized thatthis instrument had last been overhauled about 8 years ago, just prior tothe time the right vacuum pump was last replaced! So those spindle bearingswere fully depreciated, too.

Lesson #4: When making a fix-or-ignore decision on-the-road, go with yourgut feelings. They’re usually right.

The shop had a yellow-tagged AI of the same kind on the shelf for $360 exchange,and I said I’d take it. It arrived by courier and I installed it in the airplaneWednesday over lunchtime.

Glitch Number Three

Thursday I was scheduled to attend a tradeshow at Cocoa Beach withAVweb publisher Carl Marbach andanother associate, followed by a VIP tour of the Kennedy Space Flight Centerat Cape Canaveral. This involved a one-hour flight from Boca Raton to MerritIsland, a perfect shakedown cruise for the new attitude gyro.

The flight to Merrit Island was lovely and the AI and autopilot behavedperfectly. But a new glitch appeared: the right EGT needle barely registeredon takeoff, although the engine was obviously running just fine. For therest of the flight, the right EGT was completely dead.

Three equipment failures in one trip! This set a new all-time record formy 310, which had always been incredibly reliable. I decided that mynormally-hangared airplane was trying to get back at me for leaving it outsidein the humidity and rain. I also decided that the EGT gauge wasn’t a seriousenough problem to worry about, and decided to let it go until I got backhome to California.

Lesson #5: Don’t sweat the small stuff.

By the time we were done with our Cape Canaveral tour, there was a monsterthunderstorm and spectacular lightning show over the Cape. We called a cabto take us back to Merrit Island airport, not knowing whether or not we’dbe able to get out. Surprisingly, when we arrived at the airport, the weatherwas sunny…but with big storms visible in several directions. A look atthe DTN weather machine made it clear that the weather was in a line alongthe east coast of Florida, and that we ought to have smooth sailing backto Boca Raton by heading inland a bit.

As we headed out to the airplane, Carl(who is a seasoned Florida pilot) said to me, “I think we better leavenow!” I nodded and started my walk-around. “I don’t think youunderstood what I meant,” Carl said with a parental scowl. “We better leavenow! No pre-flight, no run-up. NOW!“

We jumped in and fired up. As we were about to taxi onto the runway, unicomcalled to advise that Patrick AFB (8 miles southeast of Merrit Island) hadjust evacuated the control tower due to 70-knot winds! Welcome to Florida!

It still looked fine at Merrit Island, so we took off and turned east towardthe blue skies. ATC gave us our IFR clearance aloft and was extremely cooperativewith our requested weather deviations. The flight back to Boca Raton wasuneventful, except that the right EGT was still DOA.

And Yet Another Glitch

My week in Boca Raton came and went, and Tuesday morning I was out at theairport to launch for Independence, Kansas. I had managed to schedule a visitto the Cessna single-engine facility anda test-flight of the new 1997 Cessna 182S Skylanethat afternoon.

The runup at Boca Raton was fine, the vacuum pump was still working (amazing!),the attitude indicator erected properly, and all seemed right with the world.Until about 30 seconds after takeoff.

It was then that I engaged the autopilot in preparation for picking up myIFR clearance from Palm Beach Departure. Or at least I tried to engage theautopilot. But it wouldn’t engage! I checked the breakers but none were popped.I checked the electric trim and it was working. But I couldn’t get the autopilotto come on-line. No sign of life whatsoever.

Lesson #6: If you plan on using the autopilot, pre-flight it on the ground,dummy!

After a few moments of denial, I quickly decided that the autopilot was ano-go item for a coast-to-coast solo flight. Hand flying might have beenfine for Charles Lindbergh, but not for me. Call me a wuss, but I know mylimits. I turned around and landed at Boca. Hobbs meter time for the flight:0.1 hour.

I taxied over to the radio shop at Boca Raton and explained my predicamentto the shop manager. After verifying that the autopilot indeed would notengage and that there was no obvious cause, he suggested that I fly the airplaneto Fort Lauderdale Executive, where the avionics shop at Banyan Air Service had “the bestCessna 400B autopilot man in all of South Florida.” Sounded like a plan tome.

Fifteen minutes later, I touched down at FXE and got progressive taxiinstructions to Banyan‘s avionicsshop. They were expecting me, and I was quickly introduced to their autopilottech, Sam Amberson, who (I learned) had been named “Avionics Technician ofthe Year” by the FAA in 1996.

Sam quickly pulled the autopilot computer and control head from the airplaneand set them up on the bench. They worked fine. That meant that the problemwas in the airplane somewhere. My heart sank. This could turn out to be atroubleshooting nightmare. It was now noon, so I headed off to the airportgreasy spoon while Sam had his brown-bag lunch. By the time I got back fromlunch, Sam had the airplane in the hangar, the black boxes back in the airplane,and schematics spread out on the wing. At first, he suspected a problem withthe yoke disconnect switch, but that was quickly eliminated. Next, he suspecteda problem with the attitude gyro pickoff (I had mentioned that the gyro hadbeen changed out two hours earlier, but that the autopilot had worked fineduring the shakedown flight).

Sam pulled the glareshield and checked the autopilot-to-gyro cable. Suddenly,the autopilot started working. Sam determined that by wiggling the cable,he could make the problem appear and disappear almost at will. After somefurther pushing and prodding, Sam concluded that the connector on theautopilot-to-AI cable was intermittent. He had another connector in stock(a higher-quality one than the one in the airplane) and, using a propane-firedsoldering pencil, he installed the new connector and functionally checkedthe autopilot. It worked solidly now, despite all the cable- andconnector-wiggling Sam could manage. Sam pronounced the system healthy andbuttoned up the glareshield.

The tab: about $150, including parts, labor and tax. A bargain, I thought.A less-experienced technician might have taken days to find and fix thisintermittent. Sam’s the man!

Lesson #7: Sometimes, you get lucky.

By now, it was 3:00 pm EDT and convective activity was starting to explodethroughout the southeastern states. It didn’t take me long to conclude thatthe better part of valor would be to stay overnight at FXE and launch forKansas first thing in the morning. Banyan got me a crew rate at the Sheratonand I took a courtesy van over and checked in. I phoned my contact at Cessnato tell him I’d be delayed. “General aviation, you know,” I joked.

Four Glitches Are Enough!

I’m happy to report that the autopilot glitch was the last…for this trip,anyway. I made it non-stop from Fort Lauderdale to Independence in 5+20 withoutfurther incident. And I flew the new Skylane…boy,is it ever quiet! The next day, I hopped over to Wichita for a short meeting,then flew 2+45 to Albuquerque for fuel and lunch, and finally 3+45 to SantaMaria, California…home at last! The right EGT remained dead…I’ll dealwith it this week…but the vacuum pump hung in there (knock me over witha feather!) and everything else worked fine.

Thanks for riding along. Those long-distance solo flights get lonely.