Thomas W. Wathen was born October5, 1929, in Vincennes, Ind., across the Wabash River from O’Neal airport. Theairplane bug bit early. He built model airplanes, became a Civil Air PatrolCadet, and traded airplane rides for work around the airport. He graduated fromIndiana University in 1951 with a degree in Police Administration. He joined theAir Force, was stationed at Wright-Patterson AFB and the Pentagon, and served inthe Office of Special Investigation from ’52 to ’54, then became a programsecurity director at North American Aviation on the B-70 and X-15. After NorthAmerican he became the west coast security director of RCA, then the firstsecurity director of Mattel. In 1964 Tom began his own private security companywith California Plant Protection, which he expanded into a national company with20,000 employees. In 1987 he acquired the historic Pinkertonagency and expanded his business to eventually employ 50,000 people in 225offices around the world. He retired from Pinkerton in 1999.

Thomas W. Wathen was born October5, 1929, in Vincennes, Ind., across the Wabash River from O’Neal airport. Theairplane bug bit early. He built model airplanes, became a Civil Air PatrolCadet, and traded airplane rides for work around the airport. He graduated fromIndiana University in 1951 with a degree in Police Administration. He joined theAir Force, was stationed at Wright-Patterson AFB and the Pentagon, and served inthe Office of Special Investigation from ’52 to ’54, then became a programsecurity director at North American Aviation on the B-70 and X-15. After NorthAmerican he became the west coast security director of RCA, then the firstsecurity director of Mattel. In 1964 Tom began his own private security companywith California Plant Protection, which he expanded into a national company with20,000 employees. In 1987 he acquired the historic Pinkertonagency and expanded his business to eventually employ 50,000 people in 225offices around the world. He retired from Pinkerton in 1999.

Tom didn’t fly during his Air Force stint, but he got his private pilotcertificate in 1958 in Dayton in an Aeronca. Shortly thereafter he bought anErcoupe and restored it, which began a series of restoration projects including Piper’sfirst PT-1, the 1934 GrovesnorHouse DeHaviland Comet, the 1938 Keith Rider R-4 Schoenfeldt Firecracker,the 1946 Volmer Jensen VJ-21 powered glider, and a replica of RoscoeTurner‘s LT-14 Meteor nearing completion in Colorado Springs. During therestorations, Tom became familiar with FlaBobairport in Riverside, Calif., and rescued it from the hands of real estatedevelopers in 2000. FlaBob is one of five sites in the U.S. picked by the EAA tohost Air Academy day camps. In August 2001, 122 fourth-graders got anintroduction to airplane modeling and sheet-metal work, and capped the day withYoung Eagle rides. Tom was anxious to show off the recent improvements to theairport, but FlaBob’s annual fly-in, scheduled for September 22 and 23, wascancelled due to the ban on VFR flight. Earlier this year Tom went to Sun ‘n Funand heard that the remnants of Stoddard-Hamilton and Arlington AircraftDevelopers were still available from the bankruptcy courts, and onApril 16 he wrote a check and got into the airplane business. He hiredMikael Via as president of the New Glasair company and recentlyannounced a policy to help Glasair and GlaStar builders who had made deposits toSHAI and AADI. Tom has logged about 3,500 hours in a variety of aircraft,served two years on an Aviation Safety Commission in the late ’80s, and wasappointed to the President’s Council of the EAA in 1987. Tom is also a lifemember of the National Institute of IntellectualProperty Law Institute.

You’ve spent your lifetime around military and private security and servedon a previous Aviation Safety Committee. How should airport security change as aresult of the tragedies on September 11th?

The commission existed from 1987 to 1989, and it was started at the behest ofsome white-knuckled Congresspersons. There had been some accidents that,frankly, I don’t even remember anymore, but they were accidents due to weatherand mechanical failures, not hijacking and criminal activity. I was appointedbecause I had a security background and an aviation background, but the thrustof our investigation had more to do with safety than security. I had justacquired the Pinkerton agency, so I was busy merging two companies, but Iattended every meeting of the committee. We did touch on airport security, butit wasn’t the focus of the commission. There were only two other pilots on thecommission, and one of them was [Cessna CEO] Russ Meyer.

Why did the commission dissolve?

We submitted our report and, typically, nothing much was done about it. I dothink it was worthwhile. It was certainly worthwhile for me, because as acommission member I got to ride in the jumpseat of a lot of airliners, and got alot of information and input from the pilots about safety and lots of othertopics — like the age 60 rule, for instance.

Should airport security be federalized?

I hope not. That isn’t necessary. They just need to specify tighter securityrequirements and be willing to pay for it. People will have to be paid more, andbe trained better, but that’s doable without federalizing it. Northrup was thefirst of the defense contractors to contract with private security, and evenGeneral Motors got rid of its security division. It’s not their core business. Ihope it isn’t federalized. Once you federalize it, it never goes away.

Let’s go back to the beginning. Tell us about growing up and how youdiscovered aviation.

I was born and raised in Vincennes, Indiana which is right on the Illinoisborder. Just across the river from Vincennes was a grass field called O’Nealairport, which is still there. The little Catholic school I went to was almostdirectly across the river from the airport, and I was one of those kids whobuilt model airplanes and when I got old enough — 12 or so — I rode my bicycleover to the airport to watch the airplanes. I pumped gas, washed planes andswept hangars, and they would put me on the floor to help stitch ribs. Most ofthe planes were Aeronca Champs and Piper Cubs — it was a small-town airport.

I could identify all the airplanes, and I was pretty good at drafting anddrawing airplanes. My grandmother taught me how to embroider, and I embroidereda set of curtains, pillowcases and a sheet with red, white and blue B-17s onthem.

It was great fun, until my mother found out that I was actually going flying.She put a temporary stop to that, but not to my interest in aviation andairplanes. I was a Boy Scout — just about everybody was in those days — and Ijoined the Civil Air Patrol Cadets after they built George Field, which is nowthe Lawrenceville/Vincennes Airport. George was an Air Training Command base andthey had a lot of AT-10s, Waco gliders and C-47s to tow the gliders. They hadsome terrible accidents with the tow ropes snapping and taking out a flyingsurface or a windscreen.

Who taught you how to fly?

I don’t remember my first instructor, he was one of the local instructors atO’Neal. But my logbook indicates a 30-minute flight in an Aeronca — probably aChamp. I was 15 or 16, but I didn’t get my certificate until I was 28 and hadgraduated college and was a security investigator for the Air Force atWright-Patterson. I bought an airplane before I knew how to fly. It was anAeronca L-3B. I had an instructor named Oscar Brabson who carried an old sockfilled with rags, forming a sort of blackjack, and he would sit behind me andteach me with that sock.

Was your goal to fly for the airlines?

| |

| Ed Marquart, Tom and Dave Davidson talk about the Marquart MA5 Charger. |

I never wanted to fly for a living. I liked airplanes more than I like flying.I’ve accumulated 3,500 hours, but that’s not very much when you spread it outover 43 years. I studied aeronautical engineering at Purdue for a year, but Iwas stymied by the math. Even long division and subtraction, much less algebraand calculus. So I wasn’t destined to be an aeronautical engineer.

Your degree was in police administration. What was your syllabus?

They taught us the rudimentary investigative techniques that were around inthose days, like fingerprint classification. It started as a training course forthe state police, and when they turned it into a degree program, I was one ofthe first five graduates of the program. In 1951 we were the only five guysoutside of California to have an education in criminology.

I couldn’t get a job as a police officer in the state of Indiana. I tried,but to my everlasting benefit, I couldn’t, and I got a job with the Air Force asa security investigator at Wright-Patterson AFB. My first boss was a fullColonel who had been called back to active duty during the Korean situation. Hewas made Provost Marshall at Wright-Patterson and he had been the Chief ofPolice in Sacramento.

I went early for my job interview at the Provost Marshall’s office — I wasat least an hour early — and in walks this big guy with eagles on his collar. Ihad been a Civil Air Patrol Cadet, so I knew what those eagles meant. I jumpedto my feet and he said "Good morning, son. Why are you here?" I said"Well, sir, I’m here for an interview as a security investigator." Hesaid "What makes you think you can do that job?" and I said"Well, sir, I just got a degree in police administration from IndianaUniversity." He said "Come into my office!" and two and a halfhours later he took me out to the guy I had missed the appointment with and toldhim to hire me.

What was Wright-Patterson like in the early ’50s?

It was fun and a very exciting place to be. Because I had a security pass Icould wander anywhere I wanted, so I took my brown paper bag and went over tothe flight line every day for lunch. I thought I had died and gone to heaven. Idid vulnerability surveys, which meant I would try to penetrate the securitythat we had set up. I found where people had written the combinations to theirsafes and opened them and gave back their documents the next morning. One day Istole three mail trucks.

In October of ’52 I was about to get drafted and sent to the Army, so Ienlisted in the Air Force. I went on active duty with the OSI — Office ofSpecial Investigations — became a second lieutenant, spent a year atWright-Patterson and two years at the Pentagon. I like to say I went overseasevery morning because I crossed the river from BollingAFB to the Pentagon.I helped to write the first manual for industrial security. My wife worked forthe Civil Air Patrol at Bolling.

In October of ’54 I was a civilian again and I went back to Wright-Pattersonto work for the Dayton Air Procurement District. We had "cognizance"over Air Force defense contractors over an eight-state area. That’s when Ibought the Aeronca and learned to fly, at New Carlisle airport outside Dayton.

I left the Air Force in ’58 and became the project security officer on theB-70 — which we were building at Plant 42 in Palmdale — and the X-15, and theF-108at North American Aircraft in El Segundo, California. The 108 was never built. Igot to know Bob Hoover, Scott Crossfield. I was in the desert for the firstflight of the X-15 and that was an exciting day.

When did you start restoring airplanes?

| |

| Tom and Ray Stits, founder of Poly Fiber |

Right about that time, in the late ’50s, when I was at North American. I broughtan Ercoupe out from Ohio — no radios, but that was easy in those days — whichI based at Torrance, which was convenient because I lived in Manhattan Beach.

I started buying derelict Ercoupes that I’d find at little airports with theweeds growing up through them, and I’d cart them home, fix them up and sellthem. I still think that Fred Weick’s design was way advanced for its time —compared to the Champ and the Cub — because of all the innovative features.Even the new Citations are using the trailing-link gear that Weick popularized.

I started building replicas and restoring antiques in the late ’70s. My firstwas the Piper PT1, which I found in Ron Ruprecht’s hangar at Whiteman. It was aone-off and was Piper’s first low-wing, retractable-gear airplane. I hired a NewZealander named Ian Benny to help me restore it. Ian was a whiz at welding, andwoodwork and painting, and quite a character. I donated it to EAA in ’81 andit’s now at the Piper Museumundergoing another restoration.

The second airplane I found in Monroe, Louisiana. It was also a one-off, theVJ-21 motor glider. Ron and I flew there and talked to the guy that owned it.Our first problem was we found 40 pounds of mud daubber nests in the airplane.Ian Benny flew there and it took us about a week to take it apart and put itback together, then Ian flew it back to California. That airplane hangs at the Wingsof History museum in San Martin. The DeHaviland Comet project took severalyears, and it’s in beautiful condition except the engines had to be redone —again. We found the engines at EAA at Pioneer Airport, and I traded PaulPoberezny two rebuilt engines for his two older engines. His engines had thedrilled crankshaft which would allow for a controllable-pitch prop. We wantedthat in order to make the replica historically correct.

We’ve just completed the LT-14 Meteor. It’s a full-scale replica of theairplane that Roscoe Turner flew to win the ’38 and ’39 National Air Races. BillTurner has been working on it for four and a half years. DaveMorss is going to fly it.

Dave also flies the Comet, but General Pat Halloran has the most time in it.It’s a tricky airplane to fly. Robin Reid — Amelia’s son — is a Captain withNorthwest and he and General Halloran can both fly it pretty well. The Comet isalso at the Wings of History museum waiting for the engines to come back fromEngland. They do great work, but they’re sure expensive.

We’ve got one more replica nearing completion in Colorado Springs. That’s theSchoenfeldt Firecracker that was originally known as the Keith Rider R-4 thatTony Le Vier flew. We’re not planning to race it, but we will fly it at Reno andOshkosh.

Speaking of Oshkosh, when did you get involved with EAA?

When I first went to work at North American a friend told me about a magazinecalled "The Experimenter." I joined right away. I wasn’t really activein a particular chapter, but I enjoyed the magazine. I met Paul on my first tripto Oshkosh, and when I donated the Piper they invited me to join the President’sCouncil, and I’ve been on it ever since. I’ve always been excited about the AirAcademy and I helped raise funds for it, and we’ve had three of those academiesat FlaBob, and it’s the first time that the training has been held anywhere butOshkosh. We can have them year-round, and not just once in the summer like theone in Oshkosh.

We don’t have a beautiful lodge Jim Raybuilt for EAA at Oshkosh, but we are having great fun with the kids.

How did you wind up owning FlaBob airport?

| |

| The Vickers Vimy visits FlaBob on its jumbled journey to AirVenture 2001. |

I got interested in FlaBob when I contracted with Bill Turner to build theDeHaviland Comet about ten years ago. I was still running my own business andwhat spare cash I had was going into the Comet. After my company got bought out,I formed a foundation whose primary purpose was education in science, math andtechnology — using aviation as the medium — and it seemed logical to put theFoundation at FlaBob. I was living in France at the time, but my son Doug and myfriend and attorney John Lyon went out to visit the airport. They were told theywere too late to buy it — it had already been sold to some developers. Theywanted to keep it as an airport but nobody had come along to buy it. My sonasked "Do you have a contract?" and they didn’t. He asked "Do youhave a down payment?" and they didn’t. So he took out his checkbook andwrote a check that I covered. That’s how close we came to losing FlaBob.

We’ve paved the areas that were gravel and chewed up props, and we’ve thrownaway a lot of junk. We’ve torn down three buildings and we’re tearing down sixmore. It’s a lot cleaner and neater, and the restaurant is great.

And how did you wind up acquiring what was left of Stoddard-Hamilton andArlington Aircraft?

I’ve always been an admirer of the Glasair. I had met Bob Herendeen andwatched his airshows, and then I heard that Stoddard-Hamilton was in bankruptcyand somebody had made an offer and it was a done deal. Then I heard that onefell through but there was another offer and that was a done deal. Then I heardthat one fell through, too. I had expressed some interest in it to some friends,but it looked like it was too late.

I went to the Masters Golf Tournament — Pinkerton provides the security forit every year — and got bored there because my heart was down at Sun ‘N Fun, soI left early and went to Lakeland. That’s where I heard that the latest deal hadfallen through. I came home Friday — Good Friday — and called John Lyon andasked him to look into it. We discovered there was going to be a court hearingon the Monday after Easter, so on Easter Sunday my son, John, and my wife and Iflew to Seattle. We met most of the morning with an attorney in Seattle draftinga contract and getting a cashier’s check, and we walked into the court,presented our offer, and it was accepted. The whole deal took three minutes.

We started doing due diligence on the company and we quickly learned about ayoung attorney named Mikael Via. He had been attempting to assist the creditors— especially the builders, because he was a builder himself — to find a buyerfor the company. John and I met with him about a week later and after athree-hour meeting we decided he was the guy we wanted to run the company. Hehad a thriving law practice, but he saw the Glasair opportunity as a labor oflove, so after a talk with his family he decided to do it. He’s doing a greatjob and they’re making parts and shipping parts already.

Stoddard-Hamilton had done most of the work under subcontract, and most of itin the state of Washington. After a lot of discussions, we were able to acquireArlington Aircraft Company, and fold it into the New Glasair company. It hasonly been four months, but we’ve made a lot of progress. We were received wellat Oshkosh and got eight GlaStar orders, but no orders for Glasairs — not yet.

On July 23rd we announced a new policy for airplanes that builders had madedeposits on. We didn’t think that we could expect builders to support us unlessthey were able to consider buying a new airplane or some new parts. It wasn’tjust altruism or good public relations, it was a conscious business decision totry and be fair to people that had lost so much money. The previous people wereusing deposits on new orders to fund the parts for previous orders, because theywere sorely undercapitalized.

Every order we take will be escrowed. If you send in money you’ll get it backif we don’t deliver.

Tell us about the Pinkerton company.

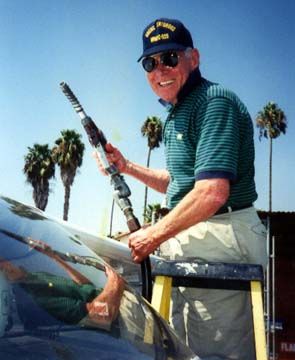

| |

| Self-serve avgas. |

Pinkerton is a venerable company, started in 1850 by Alan Pinkerton, who wasChicago’s first detective. He also founded and led the first U.S. SecretService. The company got its notoriety from its work on the railroads and trainrobbers, then it evolved into a very sophisticated organization specializing ininvestigative work. During the last 50 years the company shifted its focus frominvestigations to security guarding. The company had always been family-owned,but after the passing of the last male Pinkerton, the company went into publichands, and one of the earliest and biggest shareholders was Warren Buffett. Heultimately arranged to sell the company to American Brands. When they took over,they wanted it to become even larger, and they put it in the hands of somemarketing people whose goal was market share, at the expense of running aprofitable business. I was one of their competitors, so I knew they weren’tmaking any money. American Brands was a consumer products company and had noidea how to run a service company.

In September, 1987 I was at a security convention and read in the Wall StreetJournal that they were selling the company, and I bought it at an auction. Ipaid way too much for it, and I was already 57 years old, but we combined itwith my business and made it work. We closed 120 offices but we were able tosave everybody’s job, except for those in New York City. We offered them achance to move to sunny California, but only six out of 120 of them accepted theoffer.

Did your companies handle airport security?

The airport security business — the screening of passengers and baggage —was among the lowest-paid of all the available security work. When thosecontracts would go out for bids, they would be awarded to the lowest bidder.That has probably changed over the years, but I used to brag about not havingairport security or government work. Government work was usually set aside forminority-owned companies.

How much did we save by using the lowest bidder? How much higher was thebid to "do it right" and give us a reliable and efficient screeningsystem?

It wasn’t more than 15-20%, in my opinion. Keep in mind, however, thatplastic knives STILL won’t be found by passenger screening without a full bodysearch. Federalizing this function won’t be more efficient — only more costly.

I’m being critical of these low-paying companies, but private security did apretty good job for the last 20 years or so until September 11th. Despite itsmany flaws, it was sufficient to keep the "ordinary" bad guy fromhijacking an airplane.

You’re a life member of the National Intellectual Property Law Institute.What issues do you deal with there?

"NIPLI," as it’s called, wasformed in Washington, and they’re the people who were able to get theIntellectual Property and Industrial Espionage bill passed in 1996. There arestatues now that protect your property and criminalize its theft, and that wasas a result of NIPLI.

What’s next on your restoration/replica list?

I’m working on a replica of Rene Caudron’s M460. It’s a long, sleek narrowracer. The M360 is a fixed-gear design, and the 460 is a retractable.Michel Detroyat raced it in the ’30s and beat just about everything he ranagainst. I haven’t carved a stick or put pen to paper yet. We don’t have anymodels, but we do have the specifications, and there’s a similar airplane at themuseum at Le Bourget. Our replica will have tobe engineered like the Comet and Meteor replicas.