Eleanor Watterud Wagner was born November29, 1914, in Glasgow, Mont. Growing up in North Dakota, she and her brother spent much oftheir spare time at local airports and began a scrapbook of aviation photos and newsclips. When Eleanor was 14, the family moved from the midwest to Long Beach, Calif. Therethey found a mecca for private fliers at Daugherty Field, which is now Long Beach Airport.In 1941, she went to work for TWA in Communications and Reservation Control.

Eleanor Watterud Wagner was born November29, 1914, in Glasgow, Mont. Growing up in North Dakota, she and her brother spent much oftheir spare time at local airports and began a scrapbook of aviation photos and newsclips. When Eleanor was 14, the family moved from the midwest to Long Beach, Calif. Therethey found a mecca for private fliers at Daugherty Field, which is now Long Beach Airport.In 1941, she went to work for TWA in Communications and Reservation Control.

She learned to fly in 1943 to join the WASPs (Womens Airforce Service Pilots). The WASPprogram was cancelled just before her class was to graduate in 1944. After the war sheworked for TWA, ran flight schools in San Francisco and Palm Springs, and was America’sonly one-woman airport operator at Thermal, Calif., in the 50s. Later she relocated toL.A. and edited General Aviation News. Recent health challenges have prevented her fromenjoying the thrills and comeraderie of old friends in aviation. But she flies withfriends as often as possible and still loves aviation photography.

How did your interest in flying begin?

As early as 1927, I became interested in flying. My brother and I were fascinated withairplanes and the early barnstormers we had seen flying from the pastures and takingpeople for rides over the towns and countrysides. Then in May of that year, when I was 12years old, Lindbergh made headlines flying solo across the Atlantic in his single-engineRyan Brougham. Then came Amelia Earhart who became my mentor — I followed her aviationcareer until her untimely death in July of 1937, and I still keep track of all the newsconcerning the many theories people have as to her disappearance. My brother and I begancollecting photos, clippings, mementos and stories about Earhart and Lindbergh plus manyof the popular fliers of that era.

We built model airplanes of balsa wood and tissue paper covered with dope, and flewthem with rubber band motors. In old cigar boxes, we built crystal-set radios withheadphones. We lived in Portland, Ore., at that time but moved to Long Beach,Calif., in 1929. It was there that I should have learned to fly, but finances and thedepression of the 1930s didn’t allow us any extra money, only barely enough for ourimmediate needs. I did learn to fly later on. It was in 1943, at Sky Haven airport in LasVegas, Nev. That is now Hughes North Las Vegas airport, and had been bought by HowardHughes in the mid-’50s when he invested so heavily in properties there. The flight schoolwas owned by Howard "Dutch" Darrin, who had been a World War II pilot and became awell-known automobile designer. There were several young women flying Piper Cubs at theflight school earning enough flying time to qualify for entrance into the WASP program.For us young girls it proved to be a star-studded, exciting time in our lives.

Was Long Beach an active aviation community?

Yes, very active. It turned out to be one of the most exciting times in my earlyaviation life, and made me want more than anything to learn to fly as soon as I could. AtDaugherty Field, which is now Long Beach Municipal Airport, we often visited a flight schoolowned by Gladys O’Donnell and her husband. She was a Ninety-Nine member when AmeliaEarhart founded the national organization of women pilots on November 2, 1929. Members hadto be licensed pilots — there were 99 charter members, hence the name, which has neverchanged even though it is now an international organization with over 7,000 members.

O’Donnell was famous as a daring young race pilot, especially for her closed-coursepylon expertise. She thrilled the crowds wherever she went, but the annual Cleveland AirRaces drew the biggest crowds. That event began in 1928 and featured men and women pilotsfrom all over the U.S. and Europe in most of the events. Clifford W. Henderson founded theCleveland race and when he retired, after flying the India/Burma hump in World War II, hediscovered his own "Smartest Address on the American Desert." He developed andfounded what is today Palm Desert, Calif., near Palm Springs in the Coachella Valley.

The Long Beach airport was managed by Earl Daugherty and his wife Kay. The "airportbums" of those days were Art Goebel, Buddy Rogers and Mary Pickford, the 13 BlackCats stunt team, members of the Early Birds of Aviation, the local members of theNinety-Nines, Pancho Barnes, Bobbi Trout, Martin Jensen, Wally and Otto Timm and manyother early aviators of the era.

Who are the Early Birds of Aviation?

It’s an organization open to men and women pilots who soloed prior to December 16, 1916— the only living Early Bird died in 1998; he was 99 years old. I’m treasurer of theEarly Birds, and about 250 of us are trying to keep the organization alive — we may joinwith another organization to do that. As far as I know, there were three women EarlyBirds. I personally knew Matilda Moisant who, with her brother, operated a flight schoolin the midwest about the time the Wright Brothers were building their early trainers.There were 598 original Early Birds.

How did you get interested in the WASPs?

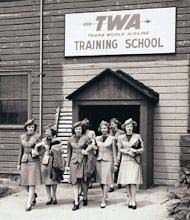

I was working at Occidental Life in downtown L.A. and insurance wasn’t theleast bit interesting to me. At lunch, I’d take walks along airline row around theBiltmore Hotel. All of the airlines had offices along 6th Street. One day I got up enoughcourage to walk into the Transcontinental and Western Airlines — which became TWA —office and ask for a job. I thought maybe I’d be a stewardess (as they were known then),but in those days you had to be a nurse to qualify. So I started studying first aid. Thenthey dropped the nurse requirement, but put in an age requirement. By that time I was pastthe age limit.

I was working at Occidental Life in downtown L.A. and insurance wasn’t theleast bit interesting to me. At lunch, I’d take walks along airline row around theBiltmore Hotel. All of the airlines had offices along 6th Street. One day I got up enoughcourage to walk into the Transcontinental and Western Airlines — which became TWA —office and ask for a job. I thought maybe I’d be a stewardess (as they were known then),but in those days you had to be a nurse to qualify. So I started studying first aid. Thenthey dropped the nurse requirement, but put in an age requirement. By that time I was pastthe age limit.

So I was teaching Red Cross First Aid and I heard about different organizations forwomen going into the war effort. First it was the WACs, the Women’s Air Corps, and Ienlisted in the first 400. Just as I was due to take my physical and get my entry papers,I heard about the WASPs. Jackie Cochran had started something called the Women’s Army AirForce to help the war effort by ferrying aircraft from the manufacturers to bases, andfrom one base to another. That’s when I decided to learn to fly and get 35 hours I neededto qualify. Because of the war, and the blackouts in Los Angeles, we couldn’t fly on thecoast. So I got the money together, went to Las Vegas, and soloed in 1943 in a Cub. Bythat time they had changed the name to the Women’sAirforce Service Pilots … the WASPs.

TWA gave me leave of absence to get the training, then I returned to work and waitedfor my call to start training in Sweetwater, Texas. I had been accepted but the wait wasnearly a year. The cancellation of the WASP program was a blow to all the women inDecember of 1944. As a result my class was not allowed to continue training so we didn’tgraduate. I felt fortunate that out of 25,000 applicants, I was one of the 1,800 that gotaccepted. Jackie Cochran and General "Hap" Arnold sent us letters expressingregrets — other than that, we got nothing.

How was the war different for female pilots?

Well, we didn’t have seniority or titles. No Colonels or Lieutenants, just pilots. TheWASPs got civil service pay, not military pay, and flew as Army Air Corps pilots with noinsurance. WASPs ferried airplanes within the U.S. and Canada, towed targets, flew VIPs tovarious bases, flew single and multiengine aircraft from base to base, factory to bases ofoverseas departure points. The flying experiences were invaluable and many WASPs went onto active military careers and other aviation ventures. They meet annually and havequarterly regional meetings. I attend our Southern California WASP Region III meetings asa "friend" of the WASPs. I’m not a military expert and my field is largelygeneral aviation, so I can’t speak for the WASPs.

After the war you went back to TWA?

During the war years, the airline changed its name to TransWorld Airlines because oftheir expansion to Europe. I went back to TWA to their new Public Relations office in SanFrancisco. In those days they called PR the news bureau. We were taught to handlepassengers with much individual care and there was no such thing as overselling a flight.Every seat had to be accounted for with a passenger’s name and waiting lists were almostunheard of. Service was different then. For instance, we’d wake the passengers in themorning. Call their hotel and remind them that they had a flight later that day. Then we’dsend a limo for them, because for a while nobody knew how to find Lockheed Air Terminal.If the passenger had special needs, like blankets or pills or distilled water, we’darrange for that. In those days the passengers were mostly celebrities or executives, andthey were used to being pampered.

We had three shifts. I’d often work the midnight to 8 a.m. shift by myself, doingreservations control for the DC3s. We had a large slanted table, like an architect woulduse. The west coast was on one end and the east coast was on the other. In the middle wereall the stops in between. Even numbered flights went east, odd numbered flights went west.We’d put the passenger’s name in and draw a line to where he was going, then we’d make a3x5 card for each passenger. The card would list any connections the passenger had tomake, or anything special the stewardesses should know.

What was Howard Hughes like in those days?

Mr. Hughes, as we called him, was eccentric — he kept his own hours, usually the weehours of the morning. When I first went to work there, my job was in Reservations Controland Communications, where we worked various shifts rotating week to week. I never sawHughes, but because I was often there in the middle of the night, I’d talk to him when hecalled to ask for special handling of people he would make reservations for. He never gaveme names, just told me to hold a seat for himself and "guest." We’d notate thebook "Orchid — handle with care" so the other shifts would know it was a Hughesrequest. Many people who worked for him never saw him — they just took their orders andassignments on the phone.

Years later, in 1954, I met him. I was at the Palm Springs airport and he was in aphone booth. I waited until he came out. He was in his usual sneakers, old sports jacketand hat. We talked for a moment about the TWA experiences. Then he went to the ramp wherehis converted A-20 was parked and took off.

How did you wind up in the desert?

How did you wind up in the desert?

I was at Belmont Airport in the bay area. My boss was killed in an airplane accident in1949. His wife asked me to stay and operate the GI flight program, the Cessna dealership,and assist the airport manager until the estate was settled. We had some 200 students,both men and women, so it was a big responsibility. I had a chance to do quite a bit offlying, too. One weekend I planned a trip to Palm Springs in one of our Cessna 140trainers. It was about a four hour flight from Belmont and I went to visit friends who hadjust built a home there. The next day when I was to leave for Belmont, I ran into one ofthe WASPs that ran the flight school at Palm Springs. She asked me to come to work forthem and offered me a good salary, so I came to work there on Memorial Day weekend of1950. It turns out that the two women who managed the Palm Springs operation, Mary Nelsonand Winifred Wood, were both WASPs.

It was a good job and I enjoyed learning about the desert. I flew over the CoachellaValley and down to the Salton Sea, to the Imperial County airports at Brawley, Calipatriaand El Centro. After a year with them, I heard about the Riverside County Airport atThermal near the Salton Sea. It had been a military airport during the war. It was foursquare miles with two 5,000-foot runways and a huge hangar, and surrounded by lushfarmlands and prosperous ranches. I took a vacation and resigned my Palm Springs job tothink over taking the Thermal Air Base lease with the county. For a lone woman it was abig decision to make.

After a quick trip to Jackson, Wyo., and a stop in Las Vegas to help George Crockett athis Alamo Airways, I returned to the desert refreshed and full of ideas. How could I doit? No money, no airplanes, no collateral, just dreams and wishes to do something I hadnever done before. The CAA (now FAA) was based in the big hangar and operated on a 24-hourschedule, so that gave me some security that I wouldn’t be completely alone. Good fortunewas with me. The president of the Desert Bank in Indio was "Torgey" Torgeson,who had been in the aviation business in Alaska. He was amazed and pleased that one womanwas taking on such a project. We negotiated, with nothing on my part except promises andhonesty, and came up with a few dollars to get me started. I lived upstairs in the hangar.The people at the bank found me a bookkeeper named Clarence Joyce, who was of great helpto me. I was able to buy two trainers and started an FBO with a CAA-authorized flightschool. I pushed airplanes, washed airplanes, fueled airplanes, dispatched the students,booked the rentals, and when somebody got hungry I cooked one of my juicy hamburgers.Pilots I knew from Palm Springs and other surrounding airports came by to enjoy the food,the music on my jukebox, and a bit of "hangar flying."

So it became more than a flight school?

I’m not an instructor. Don Green gave lessons in his own Cessna 140 and the school’stwo Aeronca Champs. In addition to Don, I was able to call on a dear friend — a WASP,interior decorator and grape rancher — who lived with her husband near Thermal Airport. Iwould call Vee Nisley, often on short notice, and she’d be there in a few minutes. Myoperation was called Coachella Valley Air Service and I did much of my own flying forphotographers, fish spotters at the Salton Sea, ranchers looking for lost cattle andhorses, and geology students doing term papers on desert rock formations.

One of the school’s Champs had a 85 horsepower engine, a Cessna landing light in thewing, and a full electrical system. If I was by myself and felt like flying I could justpull it out and start it up, without chocking and handpropping it. I eventually boughtanother 65 horsepower Champ which we rebuilt and recovered.

You were a Cessna dealer flying Champs?

Later on I joined in a venture with an airport owner nearby and we took out a Cessnadealership. We had a new all-metal 170 taildragger as our demo which I kept in the hangarat Thermal and flew passengers on sightseeing trips. The other airport was known asDesert Air Hotel at Palm Desert Airpark. It was popular nationwide and had lots of trafficin the wintertime. There were two grass runways, a round building with a dining room andlounge, a swimming pool and barracks buildings converted into hotel suites and rooms. Theowner was Hank Gogerty, a Los Angeles architect who was a pilot. It was a nice place toget away from it all. I would bring the 170 to Desert Air and fly guests around courtesyof the hotel. I had a real estate license so I showed properties from the air, too.

Cliff Henderson, founder of Palm Desert and the Cleveland Air Races, and his wifeMarian Marsh Henderson entertained friends at the resort. Jimmy Mattern, Frank Kurtz,Henry King, Art Goebel, Jackie Cochran, General Jimmy Doolittle and his wife Jo were someof their friends. Frank Kurtz and Henderson had both attended USC and reminisced oftenabout the "golden years" of flying and Kurtz’s book "Queens DieProudly," the story of "The Swooze," a B-17 he flew in the Pacific duringWorld War II. He and his wife Margo named their daughter, actress Swoozie Kurtz, after theplane.

Who were the best students?

Anyone who really wanted to fly was more adaptable and listened to the instructor andfollowed the instructions. It always helps to learn something about the history ofaviation, too. After 60 or so years of being around airports and flight schools, I got soit was quite easy to predict who the most accident-prone pilots were who thought they knewmore than their superiors. From those years of observation I found that professionalpeople, like doctors, attorneys and engineers, were the most know-it-all.

Did you ever have an emergency?

Not really, but weather seemed to be a factor in any scary situation I ever faced. Inthe desert winds and dust storms prove to be a menace and it’s important to haveinstruction in crosswind landings and to recognize wind shear. Several times I was glad tobe in the high-wing Aeronca or 170 when the air got rough.

Paul Mantz flew an airplane through your hangar?

Paul Mantz flew an airplane through your hangar?

Yes. Mantz and I had known each other over the years. He came to Thermal Airport oneday and made a colorful entrance flying his B-25 which had been converted to abubble-nosed photography airplane. He also had a crew flying other planes from theTalMantz Aviation Museum he and Frank Tallman owned at Orange County Airport. Among theseven or eight planes he brought in was a clipped-wing Stearman which he used for motionpicture stunt flying.

He asked me how much I’d charge to let him fly an airplane through the hangar. It wasonly to be the one-time shot, but it took several days of preparation doing practice runsoutside of the hangar which were flown by Bob Boone, one of his crew. I had to move all ofthe stored airplanes out of the hangar for insurance reasons and safety and there werealways little unexpected needs for the crew and the observers who had gathered to watchthe fun. Mantz walked the area measuring every angle, the width, height, altitude of hisentry and exit … he was meticulous. The day came and Mantz strapped himself into the redand white Stearman. He made a couple of passes outside the hangar as a dry run, then hedid the real thing and flew it through the hangar in once successful take. How much did Icharge? $25 a day, and I think it was a five-day session. Figures were never my strongpoint.

And that’s the same hangar that hid Chuck Yeager’s F-104?

One of the most exciting times at Thermal was the Low Altitude Speed Run for twocompany’s jets competing with one another. It was during the Korean conflict. Douglas wasbuilding the Skyray F-4D for the Navy and North American was building the F-86D Sabrejetfor the Air Force. They wanted to fly the supersonic speeds at sea level, so they pickedthe Salton Sea. We had the right atmospheric conditions for that time of year, and theycould fly at 100 feet agl and still be at sea level. (Thermal’s airport elevation is 117feet below sea level.) The course was 18 kilometers and race officials framed a racecourse by burning stacks of old tires because the pilots were going too fast to seeanything on the ground.

They kept the jets at NAS El Centro because the runways at Thermal were too short. Thatmeant that I had the press, company personnel from both contestants, their company bus andaircraft and the official race timers at Thermal when the speed run day was over. I fedthem and made sure they had plenty of cold drinks while they waited for the officials todeclare the results for each day. That’s where the Chuck Yeager and Pete Everest storycomes in.

They were not flying the runs one day and "sneaked" in from Muroc Dry Lake(now Edwards AFB), each flying an F-104. Since flying a military jet into a civilianairport wasn’t technically the right thing to do, everyone looked the other way, includingthe CAA. It was a fun experience when they took off after dark. We had no lights on therunways so North American used the company bus to guide the F-104s down the runway andback to Muroc. Both pilots did slow rolls over the airport in colorful formation withtheir lights on and made high speed passes over the field as they left.

The pilots were a loose, fun bunch, and I kept plenty of cold beer handy at the end ofthe day. The timers were another matter. The took themselves very seriously. They holed upin a corner of the hangar and didn’t want anybody talking to them.

Navy/Douglas F-4D Skyray test pilot Jim Verdin set the record at 753.4 mph. The F-86DSabre wasn’t far behind with Air Force pilot Lt. Col. William F. Barns at 715.697 mph.

How did you wind up editing General Aviation News?

How did you wind up editing General Aviation News?

I found that the work at Thermal was getting too strenuous and had been hospitalizedfor that reason, so I did not renew my lease in 1955. Instead, I earned my real estatelicense and used Desert Air as a base. It was interesting to show some properties form theair. It was a great way to sell the wide open acreage of the desert.

A businessman from Los Angeles whom I met at Desert Air met with a fatal accident thatkilled him and his partner. It was such a devastating experience for me that I was forcedto make a change and leave the desert. I belonged to the Los Angeles Chamber of Commerce’sAviation Committee and I heard of an editorial position at General Aviation News.My publisher, Sol Bender, let me travel to many aviation conferences and events around thecountry. When the paper was sold to a Texas publisher, I freelanced for variouspublications and spent some time in Vancouver, B.C., covering the Abbotsford airshow.

I went into the Yukon to Whitehorse to cover the opening of a heated hangar for thePiper dealership up there. We had a freeze-up party, which is when they convert theairplanes from floats to skis. I liked British Columbia so much I kept an apartment inVancouver for a few years. I loved the contrast of the cold wet Northwest and the hot drydesert.

When I returned to Los Angeles and the desert, I went with Northrop University inInglewood, Calif., for four years as Coordinator of Aviation Community Affairs. I workedwith Professor David Hatfield, who’s a renowned aviation historian. He was establishing anaviation museum at the University called the American Hall of Aviation History. My jobentailed fundraising and working with local Chamber members, flying organizations, earlypilots to astronauts and holding open house events at the museum. The Hall wasn’tconnected with Northrop in Hawthorne, but operated under its own cash flow. The NorthropInstitute of Technology was also a part of our group and taught students from all over theworld in its engineering departments.

Are you still flying?

Not as pilot in command or solo because I can no longer pass my physical. I do fly withfriends and enjoy aerial photography. My interests in aviation are still as active as everand I am giving away some of my memorabilia to museums, and especially to youngerindividuals who are interested in collecting photos, news clips and mementos of aviationhistory and space technology of the future. Nothing can eve replace the wonderful peopleI’ve met nor the priceless friends who have made my life such a memorable part of theGolden Years of aviation.