In-Flight Loss of Control

(The Jessica Dubroff Flight)

Cessna 177B

Cheyenne, Wyoming

HISTORY OF THE FLIGHT:

On April 11, 1996, at about 0824 mountain daylighttime, a privately-owned Cessna 177B collided with terrain after a lossof control following takeoff from runway 30 et the Cheyenne Airport, Cheyenne,Wyoming. The pilot in command, pilot trainee, and rear seat passenger (thepilot trainee’s father) were fatally injured. The pilot trainee was a7-year-old girl, Jessica Dubroff, who did not hold a pilot certificate.To be eligible for a student pilot certificate, a person must be 16 yearsold, and to be eligible for a private pilot certificate a person must beat least 17 years old. Instrument meteorological conditions existed at thetime and a VFR flight plan had been filed. The flight, which was a continuationof what was described by its promoters as a transcontinental flight “record”attempted by the youngest “pilot” to date (the pilot trainee), was beingoperated under Part 91.

On April 11, 1996, at about 0824 mountain daylighttime, a privately-owned Cessna 177B collided with terrain after a lossof control following takeoff from runway 30 et the Cheyenne Airport, Cheyenne,Wyoming. The pilot in command, pilot trainee, and rear seat passenger (thepilot trainee’s father) were fatally injured. The pilot trainee was a7-year-old girl, Jessica Dubroff, who did not hold a pilot certificate.To be eligible for a student pilot certificate, a person must be 16 yearsold, and to be eligible for a private pilot certificate a person must beat least 17 years old. Instrument meteorological conditions existed at thetime and a VFR flight plan had been filed. The flight, which was a continuationof what was described by its promoters as a transcontinental flight “record”attempted by the youngest “pilot” to date (the pilot trainee), was beingoperated under Part 91.

On the morning of the accident, the pilot in command, the trainee and thepassenger arrived at an FBO at the Cheyenne Airport between 0715 and 0730.A copy of a privately recorded videotape made by a bystander, displayinga time hack generated by the camcorder’s clock, showed the airplane beingloaded with personal effects at 0739. The ramp appeared to be dry and theairplane’s shadow could be clearly seen on the pavement. The video recordingthen showed the pilot in command and the trainee conducting portions of apreflight briefing and a taped television interview. During the interview,rain could be seen streaming off the airplane’s wings, and water was formingpuddles on the ramp.

The program director of a Cheyenne radio station conducted a telephone interviewwith the trainee and her father at about 0745. He invited her to stay inCheyenne because of the weather, but the father indicated that they wanted”to beat the storm” that was approaching.

At 0801:21, the pilot in command telephoned the Casper, Wyoming, AutomatedFlight Service Station for a briefing for a VFR flight from Cheyenne to Lincoln,Nebraska. The briefer advised of deteriorating weather moving in from thewest, an AIRMET for icing, turbulence, and flight precautions for IFR conditionsalong the route of flight. The briefer described current weather conditionsat several points east of Cheyenne, and the pilot in command said, “yea,probably looks good out there from here…lookin east looks like the sun’sshining as a matter of fact. The briefer gave the forecast for Cheyenne through0900 local time which called for 2,000 scattered to 4,000 broken with lightrain, thunderstorms, and after 0900 local time lowering ceilings to 1,500feet along the route of flight, and that rain, fog and thunderstorms wereforecast for several points along the intended route of flight. He stated,”so…if you can venture out of there and go get east it looks…,” to whichthe pilot in command replied, “yea, it looks pretty good actually.” The brieferthen made reference to the “adverse conditions” currently at Cheyenne, andthe pilot in command said, “yea, it’s raining here pretty good right now[,I] mean it’s you know steady but nothin…bad and to the east it looks realgood.” He then filed a VFR flight plan to Lincoln.

At 0813:06, the pilot in command contacted the Cheyenne Air Traffic ControlTower requesting clearance to taxi and, at 0813:24, the local controlleradvised the pilot to “taxi to runway three zero, verify you have ATIS echo.”The pilot responded, “negative, what’s the ATIS?” He was given the ATIS frequencyof 134.425 MHz and was requested to “advise when you have echo.” The pilotadvised he would get the ATIS on frequency 134.25, and the controller correctedhim by repeating the correct frequency, 134.425.

In a segment of private videotape which did not have a time hack recordedon it, the airplane’s engine was shown running, the airplane’s external lightswere on, and the nosewheel was still chocked. Rain was falling and therewas standing water on the ramp. The recording stopped, and when it resumed,the airplane’s engine was no longer running and the airplane’s external lightswere off. A lineman could be seen removing the nosewheel chock, after whichthe airplane’s external lights came back on and the engine was restarted.The airplane then taxied from its ramp location southeasterly along the paralleltaxiway to the approach end of runway 30.

At 0815:39, the pilot in command radioed the controller, “I don’t get fourtwo five on this radio,” in reference to his inability to receive the ATIS.The controller responded, “Cardinal two zero seven roger, runway three zero,wind two eight zero at two zero occasional gusts three zero altimeter twoniner seven zero.” No response was received from the pilot and, at 0816:00,the controller asked for an acknowledgement. The pilot responded “OK, twozero seven, are we going the right way for runway 30?” The controller responded,”you are heading the right way for runway 30, did you get the numbers?” Thepilot acknowledged, “we got em.”

At 0818:12, the controller advised the pilot that a Twin Cessna just departedreported moderate low-level wind shear plus or minus one five knots”and the pilot responded, awe got that thank you.” At 0818:53, the localcontroller advised that “tower visibility Es] two and three quarters [ofa mile], field is IFR and say request.” The pilot responded, OK two zeroseven would like a special IFR um ah right downwind departure.” The controllerresponded, “I’m not familiar with special IFR” and the pilot corrected with”I’m sorry, special VFR.”

The tower local controller then coordinated with the local radar controllerand, at 0820:19, advised the pilot that he was “cleared out of [the immediateairport vicinity] to the east, maintain special VFR east, maintain specialVFR conditions,” which was acknowledged by the pilot in command.

At 0820:51, the local controllerinquired “let me know when you’re ready,” and at 0820:56 the pilot responded,”two zero seven’s ready.” Although the controller did not radio a takeoffclearance until two seconds later, the airplane had already started its takeoffroll.

At 0820:51, the local controllerinquired “let me know when you’re ready,” and at 0820:56 the pilot responded,”two zero seven’s ready.” Although the controller did not radio a takeoffclearance until two seconds later, the airplane had already started its takeoffroll.

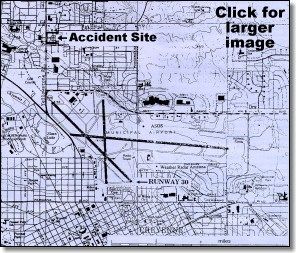

Ground witnesses observed the airplane depart runway 30 heading in anorthwesterly direction, and then execute a gradual right turn to an easterlyheading. The witnesses generally described the airplane as having a low altitude,low airspeed, high pitch attitude, and wobbly wings. As it was rolling outof the right turn at several hundred feet AGL, the airplane was observedto rapidly descend to the ground in a near-vertical flight path. Theimpact occurred approximately 4,000 feet north of the departure end of runway30 in a residential neighborhood.

PERSONNEL INFORMATION: Pilot In Command: The pilot in command was52 years old and was a stockbroker by profession. He held a commercial pilotcertificate with airplane single-engine land and instrument ratings,and a flight instructor certificate with an airplane single-engine landrating. His flight records for the two years preceding the accident revealedthat he had given flight instruction to eight students in addition to thepilot trainee on this flight during that time. A search of FAA records showedno violations or enforcement actions. He instructed students through a flyingclub which he helped organize at his home base of Half Moon Bay Airport,Half Moon Bay, California.

The NTSB reported that, according to another flight instructor at the HalfMoon Bay Airport, during one instructional flight he attempted to taxi outwith the tow bar still attached to the airplane. This flight instructor alsoreported that the pilot in command had developed his own instrument approachinto the Half Moon Bay Airport that went down to 500 feet.

The pilot in command had a current second class medical certificate withthe limitation that “holder shall wear lenses that correct for distant visionand possess glasses that correct for near vision.”

According to the pilot’s logs, as of April 8, 1996, he had a total time of1,484 hours. He had not logged any instrument time during the six monthspreceding the accident. Records indicated that he had conducted 10 flightsfrom airports located above 4,500 feet MSL.

Pilot Trainee: The pilot trainee did not hold any FAA certificates.Her total instructional time as reported in her personal flight log throughApril 6, 1996, was 33.2 hours. All of the flights occurred in Cessna aircraft,including 3.7 hours in the accident 177B. A total of 29 flights were logged,all with the pilot in command as her instructor.

SLEEP AND ACTIVITY HISTORY: On Wednesday, April 10, 1996, the airplanedeparted Half Moon Bay, California, at 0700 p.d.t., and landed at Elko, Nevada,at approximately 1020 p.d.t., and was refueled. The airplane departed Elkoat 1115 p.d.t, and arrived in Rock Springs, Wyoming, approximately threehours later. The airport manager at Rock Springs said the pilot in commandwas “noticeably exhausted.” The pilot in command telephoned the Casper, Wyoming,Automated Flight Service Station and received a weather briefing for theflight to Cheyenne, Wyoming. The airplane departed Rock Springs at approximately1540 and landed at Cheyenne at approximately 1726. The pilot in commandtelephoned his wife from the airport and said that he was elated at thereceptions they had received. According to his wife, he sounded tired, andhe stated that he was very tired.

The program director for a local Cheyenne radio station provided transportationfor all three occupants from the airport to the hotel. During the ride, theydiscussed a storm front that was predicted to arrive in Cheyenne the nextmorning. According to the program director, the pilot in command was “veryadamant” that the flight should depart by 0615, and the pilot trainee’s fatheragreed. The program director stated that all three looked tired and discussedbeing very tired. Upon arrival at the hotel at approximately 1900, the pilottrainee and her father checked into one room and the pilot in command checkedinto another room.

On the morning of the accident, the pilot in command checked out of his hotelroom at 0622. The desk clerk said he looked fairly rested and seemed happy.The trainee and her father checked out of their hotel room at 0714 and, withthe pilot in command, returned to the Cheyenne Airport by hotel shuttle.

AIRPLANE INFORMATION: The airplane, a four-place Cessna 177B,was manufactured in 1975 and registered to the pilot in command in 1987.Prior to the accident flight, both the airframe and engine had accumulated3,582.3 flight hours. The airplane received its last annual inspection onJuly 8, 1995, at 3,508.4 flight hours.

The airplane was equipped with dual 3-inch aluminum rudder pedal extensionson the left side rudder pedal assembly, which were installed a few weeksbefore the accident flight. Cushions on the front left seat (to raise upand extend the left seat occupant’s forward view) were visible on the videorecording made immediately prior to the airplane’s departure from Cheyenne.

The airplane was equipped with two 25-gallon wing tanks, providing atotal of 49 gallons of usable fuel. It had been topped up with 26.3 gallonsof 100LL fuel shortly after its arrival in Cheyenne.

The 1975 Cessna 177B Owner’s Manual states in Section II that prior to takeofffrom short fields above 3,000 feet elevation, the mixture should be leanedto give maximum power. According to FAA Advisory Circular 61-23B,”Carburetors are normally calibrated at sea level pressure to meter the correctamount of fuel with the mixture control in the ‘FULL RICH’ position. As altitudeincreases, air density decreases…If the fuel/air mixture is too rich, i.e.,too much fuel in terms of the weight of the air [high density altitude],excessive fuel consumption, rough engine operation, and appreciable lossof power will occur.”

WEIGHT AND BALANCE: The airplane’s maximum gross takeoff weight was2,500 pounds. The takeoff weight on the morning of the accident was calculatedby Safety Board investigators to be 2,596 pounds. The center of gravity wascalculated to have been at 110.4 inches. The aft center of gravity limitfor the Cessna 177B at its maximum 2,500 pounds gross weight is 114.5 inches.

WING FLAP SETTING: Examination of the wreckage indicated a 10 degreeflap extension at the time of impact. The airplane’s Owner’s Manual statesthat takeoffs can be accomplished with the flaps set in the zero to 15 degreespositions. The preferred flap setting for a normal takeoff is 10 degrees.

WEATHER OBSERVATION: Weather observations at Cheyenne are taken byan Automated Surface Observation System (ASOS). The 0823 special observationwas: sky condition – 1,600 feet scattered; measured ceiling – 2,400feet broken, 3,100 feet overcast; visibility – 5 miles; weatherthunderstorm, light rain; temperature – 40 degrees F.; dew point -32 degrees F.; wind – 250 at 20 knots, gusting to 28 knots; altimeter- 29.71; remarks broken variable scattered, thunderstorm began 0823,0.04 inch rain feel since previous record observation, wind shift began 0800,peak wind 260 degrees at 28 knots recorded at 0817.

The nearest Doppler Weather Surveillance Radar was located at the CheyenneNational Weather Service office located on the southern boundary of the airport.Velocity data from the Doppler radar indicated that the wind direction inthe airport area around the time of the accident was from about 260 degreestrue near the surface and did not shift substantially through approximately350 feet AGL. The winds were 15 to 30 knots.

Investigators asked the tower controller why runway 30 was in use at thetime. He reported that at his console, the wind readings, which did not comefrom the ASOS, indicated that the winds were variable and did not favor eitherrunway 30 or runway 26. He also said that the accident airplane was parkedcloser to runway 30 and would be able to depart faster using that runway.The controller’s wind readings came from a National Weather Service anemometerwhich was located near the threshold of runway 30. No record was kept ofthe wind directions recorded by that anemometer.

OTHER PILOTS: A pilot with the State of Wyoming, who is based at Cheyenne,holds an ATP rating and has more than 13,800 flight hours, departed fromrunway 30 in a Cessna 414 at 0816. He told investigators that his radar painteda steep gradient of green/yellow/red echoes beginning about four to fivemiles from his position on the runway. He requested a 60 degree turn to theright (heading 360 degrees) immediately after takeoff. While on the runway,he observed cloud to ground lightning to the west. The strongest part ofthe storm appeared to be at about 230 to 240 degrees with echoes extendingto about 330 degrees. The pilot recalled strong crosswinds during his takeoff,requiring significant aileron input. He said he experienced control difficultiesall the way down the runway, more than he would normally expect under thosewind conditions. After rotation, the airplane did not accelerate rapidlyat first. He said he experienced moderate turbulence and the airspeed fluctuated+/-15 knots. He said that the airplane began to climb satisfactorilyafter leaving the airport boundary. At 200 to 300 feet AGL, the turbulenceand airspeed fluctuations subsided.

The pilot of the Cessna 414 reported that he was aware that the accidentairplane was planning to take off soon after his departure and that he wasconcerned and gave a pilot report to the tower hoping that the pilot of theCessna 177B would hear it. He said that he never talked to anyone in theaccident airplane.

The captain of United Express flight 7502 (a Beech 1900) landed at CheyenneAirport at about 0820. He remembered that as the airplane taxied to the gate,the rain showers became heavier. He remembered hearing the pilot report fromthe Cessna 414. The captain said he decided to delay his planned takeoffuntil the weather improved. He said that he observed lightning within oneor two miles of the airport as his airplane arrived at the gate, and thatthe rain changed to what appeared to be small hail.

AIR TRAFFIC CONTROL: The Cheyenne ATCT local controller who was onduty at the time of the accident reported that the weather began deterioratingshortly after he took his position shortly before the accident. He recalledthat visibility was lowest from the southwest through the north and was betterto the east and southeast. He said that the worst weather was in the northwest,and that the weather seemed stationary. At 0818:12, he advised the accidentairplane that “twin Cessna just departed reported moderate low level windshearplus or minus one five knots.”

He said that the accident airplane did not come to a complete stop at thebeginning of the runway, and that it was rolling when he gave the takeoffclearance. He stated that after becoming airborne, the airplane appearedslower than expected.

WRECKAGE AND IMPACT INFORMATION: The airplane came to rest on thesouth edge of a level, residential street at the entrance to a privateresidential driveway. The final resting spot was nearly the same as the initialpoint of impact. The crash site was on a bearing of 321 degrees and 9,600feet from the departure threshold of runway 30. The wreckage distributionwas largely confined to the immediate ground impact site, but a distributionof small fragments extended from the ground impact site southeast into aresidential yard.

The airplane was upright and was oriented along a southeast heading. Thenose section and forward cabin area were crushed. Both cabin doors evidencedcrush lines which indicated that the airplane impacted at a 67 degree nosedown attitude.

The two-blade propeller was separated from the engine. One blade wasbeneath the left wing. The other blade was embedded in the ground impactcrater. Both blades exhibited tip curl and blade twist, along with extensivechordwise scratching and small leading edge nicks.

The entire wing structure remained essentially intact, but had separatedfrom the airframe.

The mixture control knob was found in the full rich position. A damaged videorecorder and two blank videotapes were found at the wreckage site. No videotapewas found inside of the recorder.

Approximately 15 pounds of navy blue baseball caps were recovered at thesite. The baseball caps displayed the pilot trainee’s name in gold letteringalong with the slogan, “Sea to Shining Sea” and “April 1996.”

MEDICAL AND PATHOLOGICAL INFORMATION: The Wyoming State Crime Laboratoryconducted autopsies on the accident victims. The reports concluded that allthree victims died from traumatic injuries. Injuries sustained by the pilotin command, including fractured wrists, fractured ankles and fracturedfeet, and the lack of comparable injuries to the pilot trainee, indicatedthat the pilot in command was operating the controls of the aircraft at impact.

The autopsy report on the trainee’s father noted that his left shirt pocketcontained “numerous slips of paper with appointment times and dates of TVinterviews,” including one scheduled for that evening in Ft. Wayne, Indiana,and another for the next evening in Massachusetts. There also were numerousbusiness cards from radio stations, TV stations and networks.

MEDIA ASPECTS: The pilot in command’s wife reported that her husbandwas “flabbergasted” by the media coverage. ABC News had provided a videorecorder to the trainee’s father along with three blank video cassettes torecord the first day’s flight activities. The first three tapes were to beturned in to ABC News at Cheyenne, and were to be replaced with blank tapecassettes for additional recording.

Numerous media representatives were present when the flight departed HalfMoon Bay, California, and the occupants of the aircraft were interviewedon live national television at 0530 that morning. Upon arrival at Cheyenne,a large number of spectators, including news media, were present at the airport.There was a welcome presentation by Cheyenne’s Mayor. On the morning of theaccident, the airplane occupants participated in at least three media interviews.

…he considered the flight a

“non-event for aviation” and

simply “flying cross country with

a 7-year-old sitting next to you

and the parents paying for it.”

ITINERARY PLANNING: The idea for the “record”-attempting crosscountry flight was proposed by the trainee’s father in February, 1996, accordingto the trainee’s mother. The original plan was for the trainee and the pilotin command to fly from California to Massachusetts and to complete the tripby May 5, 1996, which was the trainee’s eighth birthday. It was agreed thatthe pilot in command would be paid his normal hourly rate for flight instruction,with additional compensation for the non-flight time. According to thepilot in command’s wife, when the flight was first conceived, he did notexpect publicity. She said that he considered the flight a “non-eventfor aviation” and simply Flying cross country with a 7-year-oldsitting next to you and the parents paying for it.” She said that he originallyplanned to return from the East Coast with a business partner after the tripwas over.

According to the trainee’s mother, about one month before the trip the traineeasked her father to go with her and he agreed. Two to three weeks beforethe trip, the itinerary was expanded to involve approximately 51 hours offlying over eight days, with no days off, and included planned visits torelatives and other events. The outbound trip was to originate at Half MoonBay, California. The first day’s stops were: Elko, Nevada; Rock Springs,Wyoming; overnight in Cheyenne, Wyoming. The second day’s stops would be:Lincoln, Nebraska; Peoria, Illinois; overnight in Fort Wayne, Indiana. Thethird day’s stops would be: Cleveland, Ohio; Williamsport, Pennsylvania;overnight in Falmouth, Massachusetts. The fourth day’s flight would stopat: Frederick, Maryland; overnight in Clinton, Maryland. The fifth day’sflight would stop at: Raleigh, North Carolina; Charleston, South Carolina;Jacksonville, Florida; overnight at Lakeland, Florida. The sixth day’s flightwould stop at: Marianna, Florida; Mobile, Alabama; overnight in Houston,Texas. The seventh day’s flight would stop at: San Angelo, Texas; Albuquerque,New Mexico; overnight at Sedona, Arizona. The schedule for the eighth daywas a stop at Lancaster, California, and a final destination of Half MoonBay.

PREVIOUS RECORD ATTEMPT: Investigators could find no organizationwhich keeps an official record for “the youngest pilots The father of an8-year-old boy who flew with his father across the United Statesin July, 1995, to set a self-proclaimed “youngest pilot flight record”was interviewed by Safety Board investigators. The 8-year-old boydid not hold any FAA certificates. The father reported that a local newspaperpublished a short item about the flight the day before it began, and thatwithin an hour of the newspaper’s publication he was contacted by two radiostations. He said that by the time of departure, there was a media “frenzy”at the airport. He said one reporter explained that “we’re looking for ahappy story on kids.”

ANALYSIS: The pilot in command was properly certificated and qualifiedfor the intended trip. Additionally, evidence indicated that he was wearingthe corrective lenses required by his medical certificate at the time oftakeoff.

There was no evidence that airplane maintenance was a factor in the accident.Because the ground temperature was above freezing up to the time of the takeoff,and because of the short duration of the flight, airframe icing was not likelya factor in this accident.

THE ACCIDENT SCENARIO: The statements provided by witnesses indicatedthat the airplane’s climb rate and speed were slow and that after the airplanetransitioned to an easterly heading, it rapidly rolled off on a wing anddescended steeply to the ground in a near vertical flight path, consistentwith a stall.

Based on performance data provided by NASA, the Safety Board determined thatthe rainfall present at the time of takeoff could reduce the airplane’s liftby as much as three percent, increasing the airplane’s stall speed by about1.5 percent.

The Safety Board found that the pilot in command decided to turn rightimmediately after takeoff to avoid the nearby thunderstorm and heavyprecipitation that would have been encountered on a straight-out departure.Witness statements indicated a gradual turn, consistent with a bank angleof about 20 degrees. With the flaps set at 10 degrees, this turn would increasethe stall speed about three miles per hour, from about 59 mph for steadylevel flight to about 62 mph.

Because the airplane was about 96 pounds overweight at takeoff, the SafetyBoard found that this would have increased the stall speed another two percent.

The Cheyenne Airport has a field elevation of 6,156 feet MSL. Density altitudeat the time of takeoff was calculated to have been 6,670 feet MSL. Accordingto airplane performance data from Cessna, the high density altitude and theairplane’s overweight condition would have decreased the airplane’s bestrate of climb speed from 84 mph to 81 mph, with a climb rate of 387 feetper minute. Thus, the airplane had decreased performance with an increasedstall speed. However, it should have been able to climb and turn safely.The Safety Board analyzed possible reasons why this did not occur.

Investigators believe the evidence shows that the pilot did not lean thefuel/air mixture for maximum power for the high density altitude takeoff.The mixture knob was found in the full rich position at the accident scene.Although it is possible that impact forces moved the knob forward to fullrich, investigators noted that the linkage rod was not bent. Investigatorsalso noted that the pilot did not stop at the end of the runway before thetakeoff roll, which would have been the most common and appropriate timeto adjust the fuel/air mixture.

Carburetor icing conditions existed at the time of takeoff. Investigatorsnoted that without the application of carburetor heat during taxi and runup,ice may have formed the carburetor and reduced the available power at takeoff.The carburetor heat control was found in the “off” position. The pilot’sfailure to stop at the end of the runway also suggested to investigatorsthat he did not perform a pretakeoff checklist, which would have includeda magneto check and check of the carburetor heat.

The Safety Board found that although the horizontal in-flight visibilityat the time of the stall was most likely substantially degraded due toprecipitation, eliminating a visible horizon, the pilot in command couldhave maintained ground reference by looking out the side window. However,this could have been disorienting to the pilot because of the need to scanto his left to see the flight instruments in front of the trainee and tohis right to see the ground as he attempted to operate the airplane at alow speed, with a lower than normal climb rate.

The Safety Board found that the wind conditions would have made it more difficultfor the pilot in command to maintain a constant airspeed and rate of climband could have resulted in an unintended reduction in airspeed to below theairplane’s stall speed. The wind conditions also may have affected the pilot’sperception of the airplane’s speed. What was initially a crosswind duringthe takeoff roll and initial climb, became a tailwind after the airplanebegan its right turn. Because the pilot was most likely looking outside duringthe special VFR departure, he may have not been adequately monitoring theairspeed indicator, or may have had difficulty monitoring it because of airspeedfluctuations, and may have mistaken the increase in ground speed as an increasein airspeed. This may have led him to misjudge the margin of safety abovethe airplane’s stall speed.

The Safety Board noted that the pilot in command’s limited experience inoperating out of high density altitude airports should have prompted himto be cautious, in addition to his knowledge of the storm that was movingin and the report of wind shear from the Cessna 414 pilot who had just departed.

Accordingly, the Safety Board concluded that the pilot in command inappropriatelydecided to take off under conditions that were too challenging for the pilottrainee, and, apparently, even for him to handle safely.

FATIGUE: Although the Safety Board noted that the pilot in commandhad the opportunity to receive a full night’s sleep the night before theaccident, the quantity and quality of the sleep he received is unknown.Immediately before the accident, he committed several errors that are consistentwith a lack of alertness. However, the errors also could have been causedby rushing, distractions, or bad habits. Therefore, the Safety Board wasunable to conclude that fatigue was a factor in the accident.

The errors included:

started the engine while the nosewheel was still chocked;

requested a taxi clearance without first obtaining the ATIS;

read back a radio frequency incorrectly;

accepted a radio frequency he could not dial up on his radios;

failed to acknowledge, as requested, weather information from the controller;

asked “are we going the right way?”;

failed to stop at the end of the runway;

requested a “special IFR” clearance.

MEDIA ATTENTION AND ITINERARY PRESSURE: The Safety Board noted thatself-induced pressures from media attention can degrade decision making,increasing the perceived importance of maintaining a schedule compared withother factors. The Safety Board concluded that the airplane’s occupants’participation in media events the night before and the morning of the accidentflight resulted in a later-than-planned takeoff from Cheyenne underdeteriorating weather conditions. However, media presence at the airportand interviews scheduled on subsequent stops probably also added pressureto attempt the takeoff and maintain the schedule. The Safety Board foundthat the itinerary was overly ambitious, and that a desire to adhere to itmay have contributed to the pilot in command’s decision to take off underthe questionable conditions at Cheyenne.

PROBABLE CAUSE: The National Transportation Safety Board determinedthe probable cause of the accident was the pilot in command’s improper decisionto take off into deteriorating weather conditions (including turbulence,gusty winds, and an advancing thunderstorm and associated precipitation)when the airplane was overweight and when the density altitude was higherthan he was accustomed to, resulting in a stall caused by failure to maintainairspeed. Contributing to the pilot in command’s decision to take off wasa desire to adhere to an overly ambitious itinerary, in part, because ofmedia commitments.