Even with modern gee-whiz panel integration, there are obvious reasons why the portable com radio soldiers on. When the electrics quit, it could be the last tool in the bag for talking your way down for a landing (and for some, an instrument approach), it’s useful for preflighting and copying a clearance when you don’t want to turn on the master switch, and for some, it may be the one and only radio when flying aircraft without electrical systems or avionics.

As you’d expect, portable com radios have advanced (yet slowly)—some sporting Bluetooth, GPS and other features you may not use or get along with, especially if the radio will be used for belt-and-suspender backup. That means choosing the features you’ll actually use. Herewith is a scan of the relatively slim market.

Spec the Basics First

Before shopping, think hard about how you’ll actually use the radio and based on that, how it should be powered. If it’s primarily for emergency use, battery consideration is important. For emergency use I favor AA alkaline power, and not Li-ion rechargeable. Remember, the radio might sit in the bottom of the flight bag or in a map pocket for long periods and inevitably when you need it most, that rechargeable battery might be flat. With AA power, at least you can carry a spare set should you need them.

Do you want and will you really use navigation functions? Icom, Sporty’s and Yaesu all have models with built-in nav capability—GPS and analog VHF for ground-based navaids, including ILS with onscreen CDI. These navigation functions perhaps had more utility before everyone flew with tablets running navigation apps, so when choosing a handheld com, raw nav capability is sort of an afterthought. Is it really practical flying an ILS with the radio in hand? I’ve tried and it’s a dance. If that’s your backup, how will you mount it?

The other things to consider are performance and simplicity. An emergency is no time to be fumbling with a complex feature set and deep menu structure, so I think simpler is better. Plug in the headset, power it up, dial the frequency and start talking. But there’s more to it. Since portable radios don’t have anywhere near the transmit power of say a 10- to 12-watt panel radio (they typically half that power and even less when radiating through a whip antenna), don’t expect to talk the distance you can with your panel-mounted rig. That means having to install a dedicated VHF antenna to connect with the radio. See the sidebar on below for more on how to do it.

Last, for inflight use, you’ll want to connect your headset to the radio, and perhaps even connect a push-to-talk switch. The Sporty’s PJ2 has a direct plug-in for the mic and phone plugs of a GA headset, but others require a separate adapter—an accessory that often gets lost in the shuffle when you need it the most. Want to listen through your headset wirelessly? One radio—the Icom A16B—does just that with a Bluetooth connection.

Icom

Icom (a staple in the land mobile com market) has enjoyed sizable success in the aviation market over the years with its line of portables, and the current flagship model is the $499 (street price) A25N. The “N” nomenclature means it has a built-in nav receiver, plus it also has Bluetooth. This radio has been a permanent extension of my own flight bag (and for use in the hangar) and has proven to be reliable, rugged and with far more features than I use. The radio ended up replacing the venerable Icom A22, which served me well—once talking me down from a real-deal electrical failure at dusk. I gave up on it when I couldn’t affordably source a replacement battery.

What I like most about the A25N is the build quality and chassis size. Weighing 13.6 ounces with the rechargeable lithium-ion battery and whip antenna attached, the waterproof Icom measures 5.8 inches high, 2.3 inches wide and 1.3 inches deep. It stands tall with the antenna attached, so you’ll have to remove the long antenna to fit the A25N into a dedicated radio pocket of a smaller flight tote, which I use. The antenna uses a quick-disconnect BNC connector, which makes it easy to saddle the radio up to an external antenna equipped with typical coax cable.

Where the early-gen A22 and other Icoms had 5 watts of transmit power, Icom built the current transmitters with 6 watts (every bit counts). When it’s not in service, I leave the radio plugged in to the standard desktop drop-in charger, and Icom sells a cigar lighter plug for powering it in the airplane. Still, I think it’s time Icom added a USB-C power port for on-the-fly charging from a power bank or panel USB power port. Battery endurance is spec’d at roughly 10 hours, but you can expect a lot less when transmitting—the duty cycle of the transmitter on portables eats power.

But the A25N is still efficient; I put it on the test bench and measured a 1.8-amp current draw while keying the transmitter for 10 seconds. If the radio is used for emergencies, I suggest buying the optional AA battery pack. I’ve grown to like the on-screen battery strength indicator, which works with the standard rechargeable cells and with the optional AA pack.

The Icom comes standard with a headset adapter, which can be used with a portable push-to-talk switch. During transmit the radio generates artificial sidetone (the sound of your voice you hear in the headset) just like a panel com. That’s more useful than you might think. Using the radio without headsets means keying the switch on the left side of the chassis and talking into the microphone on the front grill. Speaker volume is adequate, but again, in the real world it’s better paired with a headset—especially in loud cabins. That struggle is real. One thing that is improved over older Icom radios is the display—a large 2.3-inch LCD screen with a day and night mode. Hit with bright sunlight it does fine, and it’s easy to crank down for a dark cockpit. There’s also a contrast adjustment that’s easy to tweak.

The A25N’s ergos are decent, but after not using it for a while I still struggle with finding the darned power key, which is on the lower left area of the keypad. Icon ought to color the key red or green so it doesn’t get buried. You can set in the active frequency with the keypad or use the rotary dial at the top of the case, which I prefer. And so you don’t inadvertently tune it off frequency, you have to press the Function key for fingering the frequency buttons, plus the keypad has a lock—plenty of failsafe for ham-fisted users like me.

The radio has plenty of advanced features, including a squelch level adjustment (two buttons on the side of the chassis) with a dedicated onscreen squelch graphic that shows the triggering level that’s set. Even better is the ANL feature, for automatic noise limiter. It’s supposed to help clean up noise (engine ignition, for example) that might sneak into the com receiver. When the receiver has an incoming signal, RX is displayed on the screen. For emergencies, there’s a dedicated one-touch 121.5 MHz key, but don’t forget to hit the Function key to activate it.

One thing I never use is the 300-channel/15-group storage memory bank, where you can name channels and assign them a type. This includes GND, CLR, APP and other com and nav acronyms. There’s also frequency recall and a VFO scanning mode that sweeps the entire band. The other feature I never use is the onboard VHF nav receiver, which is limited to VOR—no ILS. When the nav band frequency is in use, the set displays a CDI screen with a basic compass rose, CDI, OBS value indicator, the heading to or from the VOR station and a TO/FROM indicator. The nav functions are accessed via the keypad by pressing the Function key and then the corresponding nav function on the 1,2,4,5 and 6 function keys.

There’s also built-in Bluetooth for loading in flight plans (based on lat/long coordinates) from Icom’s RS-AERO1 tablet app. Once the data is in the radio, the built-in GPS/GLONASS provides navigation guidance. Don’t look for topo or map data on the A25N’s display—it’s not that advanced. The display shows estimated time en route, speed over the ground, distance to destination and display range. It also stores waypoints in memory and saves transferred flight plans previously built on the app and sent over via Bluetooth, plus you can edit and delete them in the radio’s Manage FPL menu. Again, with better utility available in even the most basic navigation apps, I wonder how many users even bother with the Icom’s nav and flight plan features. What is useful for me is the NOAA weather receiver. I use it all the time for fetching conditions and forecasts.

Icom sells a com-only version—the A25C—(without Bluetooth) that’s street priced at $449. For the small price delta, I think it makes sense to spring for the flagship A25N. But there’s also the $259 Icom A16 series, including the Bluetooth-equipped A16B that’s street priced at $299. It’s a bare-bones radio, but with a 6-watt transmitter and loud (1500mW) speaker. It also has a large-capacity battery pack with 17 hours of advertised endurance when not transmitting and with the Bluetooth and LCD display backlighting turned off.

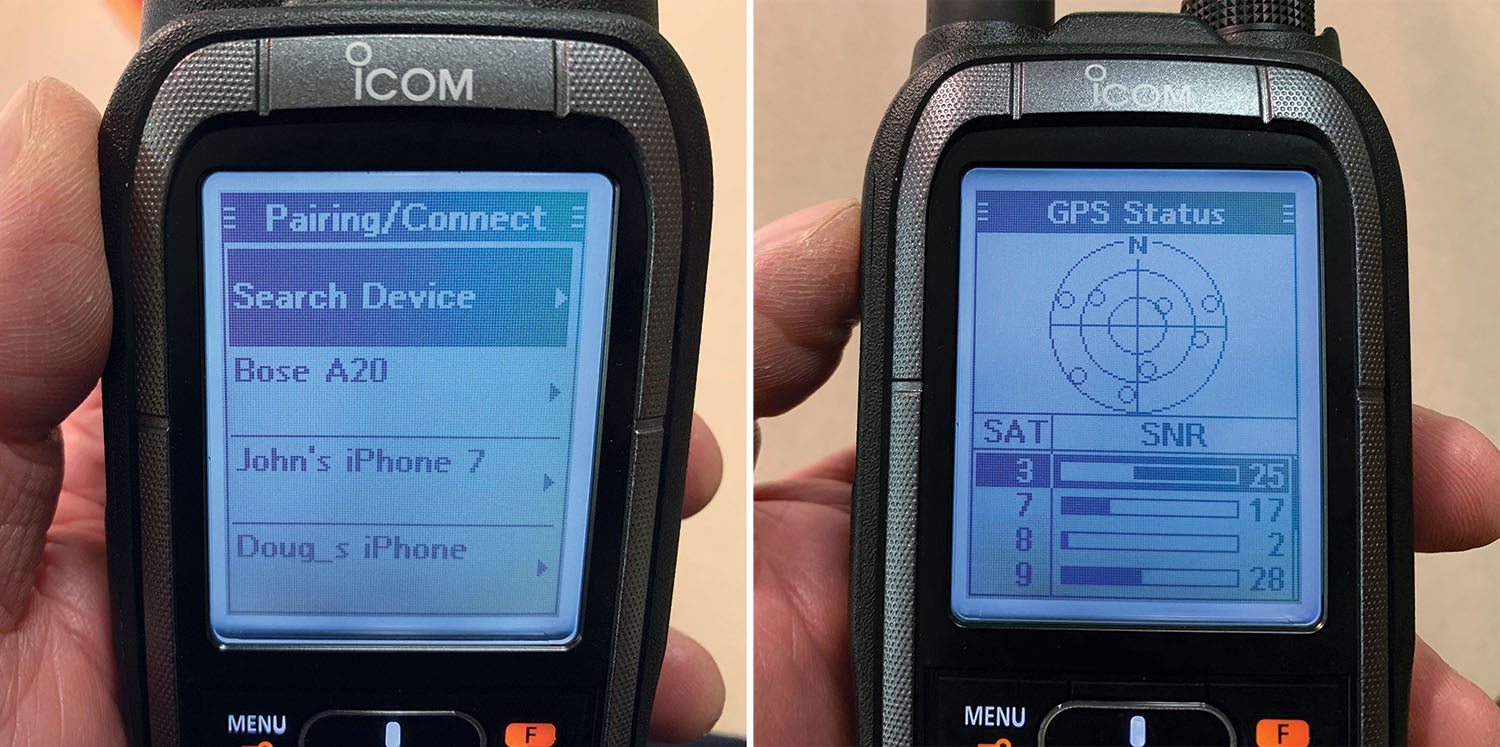

Pairing the A16B Bluetooth to a headset is a bit roundabout, and for some might be awkward compared to the way we’re used to pairing devices. Press the Function key and hold the Set key for one second, which puts the radio in Settings mode. The MR button (not the arrow keys, as you might expect) is used to scroll into yet another menu where you scroll some more to find the Bluetooth settings. Then back to MR for pairing. Once you do it a few times it may be easier, but I think Icom can do better and buyers will expect it.

But Icom built in some of the good features it uses on the flagship A25N, including the ANL noise-limiting circuit, transmit sidetone, NOAA weather radio, and a programmable 200-channel memory storage bank. The A16 series weighs 9.1 ounces and measures 2.1 by 4.4 by 1.3 inches with the BP-280 whip antenna. You can pair the radio with Bluetooth headsets (up to four of them at once) for listening to the receiver audio. There’s a version without Bluetooth street priced at $259, but the savings doesn’t seem worth it. Visit www.icomamerica.com for more information.

Sporty’s

We covered the $199 Sporty’s PJ2 handheld in the March 2020 issue and also in video, so we’ll summarize it here. Sporty’s set out to offer a radio that’s simply easy to use without a lot of bells and whistles. Made exclusively for Sporty’s by Rexon in Japan, the PJ2’s key features include standard headset jacks on the top of the chassis so you won’t need a separate adapter to plug in, a USB-C plug-in for backup power input, and an AA alkaline battery pack.

But even for the low price, the radio seems to have just enough features that buyers might expect. It will store up to 20 frequencies and has a last-frequency flip-flop (handy when the radio is used as a primary.) It also has NOAA’s weather channels. I’ve been using the radio for a year and find it stone simple to use—turn it on, key in all six digits of a frequency, and the radio will automatically tune it without you having to press the enter key. There’s also a single button to flip one frequency to the standby window like you find on a panel radio.

The simplicity continues throughout the chassis and feature set. There are dedicated volume and squelch knobs, an oversized backlit (and adjustable) display, simple oversized keys and a transmit/receive indicator light to guard against a stuck microphone.

In the real world, the PJ2 is a decent performer, but like most portables it won’t talk the distance (it has a 5-watt transmitter) without an external antenna. Its receiver sensitivity is quite good, able to pull in a signal almost as well as some panel radios. Connect the radio to an external antler and it should perform quite well.

We’ve heard of some owners having battery pack issues with early production PJ2 radios, and as expected, Sporty’s stepped up and provided redesigned replacement packs free of charge. It’s the kind of exceptional customer service that pays back big when you run into a problem, proving that where you buy is as important as what you buy.

Although it’s getting long in the tooth, Sporty’s still sells its VOR/ILS-equipped SP-400 radio priced at $300. Several SP-400s have been in the long-term test pool at sister publication Aviation Consumer for years, where they have mostly survived the test of time.

Measuring 6.54 inches tall, 2.35 inches wide and 1.46 inches deep, the radio is one of the larger ones on the market, but I think it’s also one of the easiest to use (along with the PJ2). The controls are simply placed right where you might expect them to be, including a dedicated volume (which also serves as a power control) and squelch rotary knob on the top of the chassis. The display was updated a few years ago for the better, and it works well in sunlight and has enough adjustments for tweaking it in a dark cabin.

Don’t look for lots of advanced features on the SP-400—there aren’t many except for a 20-frequency storage bank, NOAA weather radio and, as a deal-sealer for some, VOR and ILS capability. I put one on the nav test bench, injected a signal and found that the receiver sensitivity was close to that of a vintage nav/com radio—impressive. The built-in electronic CDI is utilitarian but gets the job done. You’ll need the optional headset adapter if you want to plug in your headset. I have no issues recommending the SP-400, especially if you want a good-performing nav receiver with glideslope. But I suspect Sporty’s might offer an updated replacement, especially since the SP-400 has sold well over the years. I’ll keep my eyes open for it. For more information visit www.sportys.com.

Yaesu

The Yaesu brand is no stranger to portable transceivers, excelling with products for the amateur radio market. My Yaesu Ham HT rig from the early 1990s still works, and the company has been selling aviation handhelds for a while. The company’s Vertex Standard line of land mobile equipment (which included airband transceivers) was taken over by Motorola during a division merge. Yaesu continues to manufacture the aviation radios, but dropped the Vertex name.

The flagship is the FTA-750L (street priced at $379), which has a 66-channel built-in GPS engine, a VHF nav receiver with VOR and ILS, and a compact chassis with a lot of features packed inside. The waterproof (PIX5 rated) chassis measures 5.2 by 2.4 by 1.3 inches and sports a 1.7 by 1.7-inch full dot matrix, adjustable backlit LCD display. It’s a mediocre performer in bright sunlight, although it does have a contrast adjustment for some tweaking. The 750L is powered by a high-capacity Li-ion battery pack, and also accommodates a six-AA alkaline battery tray.

In my view, the radio’s GPS falls short because it doesn’t have the functionality you might expect from a portable GPS navigator as it doesn’t have a database of airports and navaids. Instead, you either manually enter or download the lat/long coordinates of the waypoints with Yaesu’s YCE01 programming software connected to a PC via USB cable. The feature set is menu driven and at first seems complex, but it’s actually pretty logical. A dedicated Menu key and bezel-mounted arrow keys (or use the inner rotary knob) move you around the menu structure, while an Enter key selects the function—plenty of them.

There’s also plenty of frequency storage capability—up to 200 channels—which are accessed from the Memory Book icon from the unit’s on-screen menu. It also has 15 alphanumeric character assignments for frequency recognition. The menu screen also gains access to a countdown timer, NOAA weather channels, a setup menu for adjusting the display and accessing what’s called the Split Mode, which allows you to transmit a call to a flight service station while receiving on the VHF navigation band.

The display automatically shows the CDI, based on the signal it’s receiving, including localizer and glideslope. There’s also a compass rose and an SOG (speed over ground) function, based on the unit’s internal WAAS GPS receiver—a helpful feature in an emergency—but it could be better with a full-up GPS navigator function. It does have GPS position logging, storing lat/long data at preset intervals.

As for the radio’s main feature set, the Yaesu is logically designed, and adjusting the frequency is accomplished with the outer knob on the top of the radio (or by direct keypad entry), while volume is adjusted with the inner knob. It’s just natural having a dedicated rotary knob for volume. What’s missing is a one-shot squelch control. Instead, press the squelch button on the side of the radio (below the transmit button) and then rotate the knob to set squelch threshold. The squelch settings are linear, but it could be better with a dedicated squelch knob.

One good feature is the Dual Watch mode that automatically checks for activity on a preset priority channel. For example, if an approach frequency is set to priority, the Dual Watch will monitor it for 200 millisecond intervals while you continue to operate on another frequency. This feature is similar to what’s standard on higher-end panel radios that monitor the standby frequency, and it’s nice to see it on a handheld.

The $289 FTA-550L is a defeatured version that doesn’t have GPS but shares many of the other features found on the flagship 750L. There’s also the $199 FTA-550AA version, which comes standard with an AA alkaline battery tray rather than rechargeables. The FTA-450L loses the VHF nav in favor of com only and is street priced at $249 with the Li-ion rechargeable battery pack.

Downscaled more is the FTA-250L ($209), a bare-bones com-only model with Li-ion and a more utilitarian high-resolution dot matrix display and stripped-down feature set. It’s a rugged little radio with a waterproof polycarbonate chassis and a blaring 700mW speaker. It’s pocket sized at 2.1 by 4.1 by 1.2 inches and has 250-channel memory storage. The little rig has a mega-capacity Li-ion battery (1950 mAh) and like the rest of the line comes with a removable whip antenna, headset adapter, belt clip, drop-in charger and a 3-year warranty. Visit www.yaesu.com for full details.

Portable Transceivers Compared

| Model | Street Price | Size (inches) | Battery | NAV | Bluetooth | TX Power (Watts) | NOAA WX | Antenna |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Icom | ||||||||

| A25N | $499 | 2.3 x 5.8 x 1.3 | Li-ion | VOR, GPS | Yes FLT Plan Transfer | 6 | Yes | BNC |

| A25C | $449 | 2.3 x 5.8 x 1.3 | Li-ion | No | No | 6 | Yes | BNC |

| A16 | $249 | 2.1 x 4.4 x 1.3 | Li-ion | No | No | 6 | Yes | BNC |

| A16B | $299 | 2.1 x 4.4 x 1.3 | Li-ion | No | Yes, for RX Audio | 6 | Yes | BNC |

| Sporty’s | ||||||||

| PJ2 | $199 | 2.3 x 6.0 x 1.6 | AA Alkaline | No | No | 5 | Yes | BNC |

| SP‑400 | $299 | 5.5 x 2.5 x 1.4 | AA Alkaline | VOR, ILS | No | 5 | Yes | BNC |

| Yaesu | ||||||||

| FTA‑750L | $369 | 5.5 x 2.5 x 1.4 | Li-ion | VOR, ILS, GPS | No | 5 | Yes | BNC |

| FTA‑550L | $289 | 2.4 x 5.2 x 1.3 | Li-ion | VOR, ILS | No | 5 | Yes | BNC |

| FTA‑550AA | $199 | 2.4 x 5.2 x 1.3 | AA Alkaline | VOR, ILS | No | 5 | Yes | BNC |

| FTA‑450L | $249 | 2.4 x 5.2 x 1.3 | Li-ion | No | No | 5 | Yes | BNC |

| FTA‑250L | $209 | 2.1 x 4.1 x 1.2 | Li-ion | No | No | 5 | Yes | BNC |

Top Picks

There really aren’t any bad picks, so you might choose based on feature set and an operating system you can master during high-workload situations. In many cases less is better, but if satisfying the inner geek is your goal, the two most feature-packed flagship radios in the group are the Icom A25N and the Yaesu FTA-750L—both sporting very different menu structures. I suggest trying before buying from an outlet that has a liberal return policy.

If I had to pick one, it would be close between the $199 Sporty’s PJ2 (for its simplicity and direct headset interface) and Icom’s $259 A16. For flagship features packed in a rugged chassis, I favor the Icom A25N for its intuitive menu structure, although I would spring for the $50 AA battery pack if the radio never left the airplane or flight bag. Saying that, it would be better with a USB-C backup power input like the PJ2 has. Last, for a no-nonsense radio with an ultra-compact rugged chassis and high-capacity battery, the little Yaesu FTA-250L gets high marks.

My thanks to Sporty’s for helping with the images and some of the test products. —L.A.

Antennas, Ho!

Handheld com radios, as we can see, are useful around the shop in addition to providing an inexpensive backup to your panel radio. Unless your goals are very short-range transmissions, however, you aren’t going to get the best (or even adequate) in-flight performance with the standard “rubber ducky” antenna that comes with most handhelds.

The only real alternative is a real antenna. There are several ways you can approach the problem. First, you can just install another antenna like the one or ones destined for your current onboard coms. If you’re a lover of symmetry and you only have one panel-mounted com, this is easy. An alternative is a belly-mounted antenna to supplement, say, a pair of them on top of the wing (for high-wing designs) or on the fuselage (for low wingers). Install like you would for a panel mount but terminate the coax in a BNC bulkhead connector somewhere in reach. A short jumper to your handheld will do it—and it can even be the lighter RG-142 to reduce bulk. (RG-142 isn’t as efficient as RG-400, but a short segment won’t have a big enough impact on performance to worry about.)

Some builders don’t want their airplane to become “antenna farms,” so here are some alternatives. For all-metal airplanes, consider one of the wingtip antennas, like the Archer models designed to tuck into fiberglass wingtips. They’re not as efficient as more conventional com antennas, but they’re a lot better than using the flexible antenna on the handheld itself—even if they’re not perfect, they’ll greatly extend the radio’s effective range. And no added drag.

Builders with composite aircraft have additional options. There are several commercial antennas meant to go inside a fiberglass fuselage or wing. (The main difference here is that they are self-contained in the sense they have their own ground planes; the Archer wingtip antenna must be grounded to the wing and uses part of the wing and end rib as a ground plane.) It’s common for fiberglass airplanes to have one big dipole antenna in the vertical stabilizer, so additional antennas will have be located in sub-optimal locations like the tail cone behind the baggage bay. This is OK; you’re not going to rely on this antenna for everyday use, and even a less-than-ideal location is better than hand holding.

Another option is to repurpose the flexible antenna that came with your handheld to a fixed location using a ground plane. A couple of female-to-female BNC bulkhead connectors, a bit of RG-400 or even RG-58 coax, the appropriate connectors and a bit of ingenuity building the ground plane are all you need for a simple, cheap extra antenna. Radio experts will tut-tut that this isn’t an ideal RF radiator, and they’re right. But, again, you’re simply trying to improve on the performance you’d get with the handheld literally in your palm. And that’s not hard to do, even with a sub-optimal secondary antenna.

A few last things to consider. Never try to tee into the existing antenna line unless you have a way of completely removing the panel radio from the circuit. Keep your new com antenna away from other antennas, including the ELT antenna, as much as you can. And be sure to keep all the accessories you need to put your handheld into play nearby—including the headset adapter, if needed. All this work means nothing if the connecting coax is out of reach at the back of the baggage bay when you need it the most.

—Marc Cook

Larry Anglisano is the Editor in Chief of sister publication Aviation Consumer magazine. An active land and sea pilot, Larry has over 30 years experience as an avionics tech.

This article originally appeared in the May 2021 issue of KITPLANES magazine.

For more great content like this, subscribe to KITPLANES!

Good comparison article of the most common models. I personally own both the Yaesu FTA-250L and Sporty’s PJ2. A few additional comparison thoughts:

* PJ2 is BIG and Heavy when compared to any Yaesu models. Seriously wish the PJ2 was a little smaller. FTA-250L is much easier to carry, handle and hold. PJ2 is just that smidgen too big.

* PJ2 has significantly better user interface and a frequency flop button! The FTA-250L can do more, but good luck remembering the key sequences to get it done. PJ2 is simple to use and given we use these radios infrequently, the PJ2 user interface wins. Why every radio does not have a simple flop button is a head shaker.

* FTA-250L is more rugged and durable. It instills more confidence it would survive being tossed around. The retention clip on my PJ2 broke the first time I removed it. It’s seriously lame.

* PJ2’s direct plug-in headset jack is simple terrific. Nice not to have to carry along an adapter cable.

A 20% smaller PJ2 would be the hands down winner.

Good summary article, Larry, thanks. One observation about using the AA battery packs. I have an older Sporty’s SP-400 with the alkaline pack. Since the radio uses a small amount of power to retain the memory even when turned off, you need to keep a close eye on the batteries. Twice I have managed to ignore that little chore, only to find dead and corroding batteries when I pulled out the radio for use. (Yes, I know, bad preflight planning!) Fortunately the battery box is pretty rugged and easy to clean up. But, I would recommend putting a reminder somewhere to check the batteries at least monthly, or just remove the pack when the radio will be inactive for some time. That means you will probably erase the memory, but it might save you a hour of scraping corroded batteries later on.

Also, a question for Marc Cook. While an external antenna is great for extending the transmit range of a handheld, how much power is lost depending on the length of the coax between the radio and the antenna? In other words, with a remote wingtip or tail mount, do you lose most of the range boost in the coax that the external antenna provides? And, since the ELT antenna sits idle 99.99% of the time, would it be possible to use it as your external handheld antenna feeding through a signal splitter device?

Terrific article with very useful info, Larry. I bought the Yaesu 550-AA because of the “inner geek” factor (has the NAV function) but after being very underwhelmed with the receiver performance and the insane power consumption (you could drain a fresh set of AAs in no time), it wasn’t for me. In fact I sent it back to the factory for them to sort it out but it came back as “no fault found”. I sold it and bought an ICOM A16. Night and day. Terrific radio and can’t recommend it enough.

Coax loss at VHF frequencies shouldn’t be a problem in most GA airplanes. Use a good coax, RG213 for example and you’re looking at 2.2 db at 100 mhz per 100 feet. It’ll be closer to 2.5db/100′ at the VHF aviation frequencies. There are a number of advantages in getting the antenna outside the airplane especially an aluminum one.