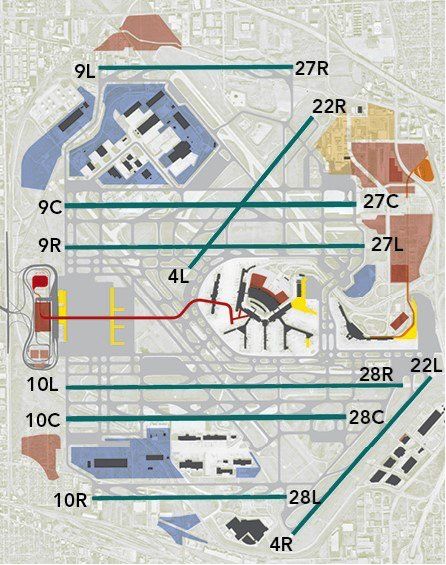

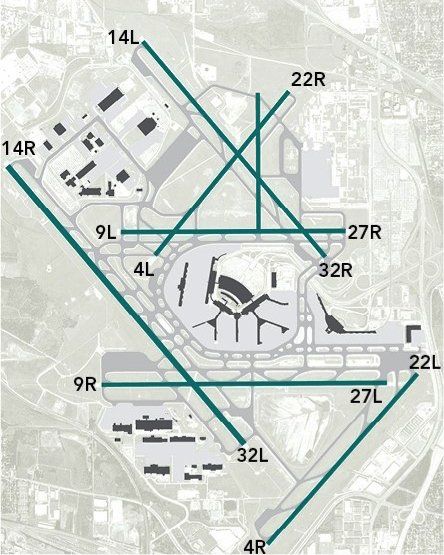

The neutering of Chicago O’Hare, once not only the busiest airport in the world, but also the baddest, is nearly complete: The 2015 version of ORD has three control towers, half a dozen east/west parallel runways … and no character whatsoever. While a couple of the old diagonal runways escaped the bulldozers, they might as well be posted “for emergency use only,” for all the use they’ll get.

So, how does operational efficiency of this new-and-improved version of O’Hare stack up against the old one? Well, in 2004, O’Hare’s busiest year, the airport logged over 992,000 takeoffs and landings. By last year, the first full year on a primarily east/west configuration, that number had dropped to 882,000. Oops.

Forgive me for sniggering a bit at those numbers, because way back when, I spent 20 years working the old O’Hare layout, from the legendary “old” control tower; most of the legends have to do with what controllers could see going on in the upper-story rooms of the adjacent O’Hare Hilton. Pumping out departures and banging down arrivals with what appeared to be reckless abandon, we moved just as much traffic then as the millennials swigging Starbucks in their three new towers do today. We had six main runways, too, but in a layout that looked like it was left over from a game of pickup sticks: all crissy-crossy, with numerous runways that intersected. Even when the runways themselves didn’t intersect, the extended flight paths to and from them did, so things were never boring—managing the myriad of crossing conflicts was a large part of the duty day.

Despite the fact that all the airplanes were aimed at each other, old hands long ago figured out ways to use the runways simultaneously in most wind/weather conditions. Aficionados of the “all parallel, all the time” school of airport design may wonder: How’d we do that? The answer is pretty much with brute force. Approach controllers would throw arrivals at the airport (with absolute minimal longitudinal separation between them), on as many as five runways at a time. Somebody would have to hold short of something, of course, but this wasn’t the legalized LAHSO of today, it was just pilots and controllers using common sense and good judgment to match aircraft capability with available concrete.

With few exceptions, airline jets could get down and stopped in 6000 feet of runway, and twin turboprops in 4500. So if there was that much or more before the intersection, that’s all they were supposed to use. If something went wrong and there was an altercation at an intersection, it might look ugly, but nobody would swap paint—controllers controlled, and asking an arrival for an S-turn on short final when necessary to prevent a DAT (dead-ass tie) at the intersection was standard procedure. Wouldn’t that be popular in today’s “stabilized approach” world!

While approach control did their best to sink the airport with arrivals, tower controllers kept the aerodrome afloat by flinging airplanes into the air off of crossing runways, shooting gaps between the tightly spaced arrivals at least one-for-one. Stories of O’Hare’s often complex “gap shots” were legend, too—while shooting departures between a single column of arrivals was ho-hum, at times there could be as many as three streams of landing aircraft crossing the path of the long-haul 747s departing off the 13,000 feet of runway 14R. The challenge for tower controllers was not only hitting the triple gap shot, but to do so without begging the tracon for help with the arrival spacing—and without catching a foul for violation of wake turbulence separation criteria. Fun times.

Between the gap shots and the never-ending flow of airplanes, old O’Hare was nirvana for the adrenalin junkies that made up most of the workforce. Even when Atlanta took away the title of world’s busiest airport, for most controllers, the O’Hare mystique remained—those Atlanta controllers weren’t shooting gaps, so they might as well be working in (yawn) Dallas or Denver.

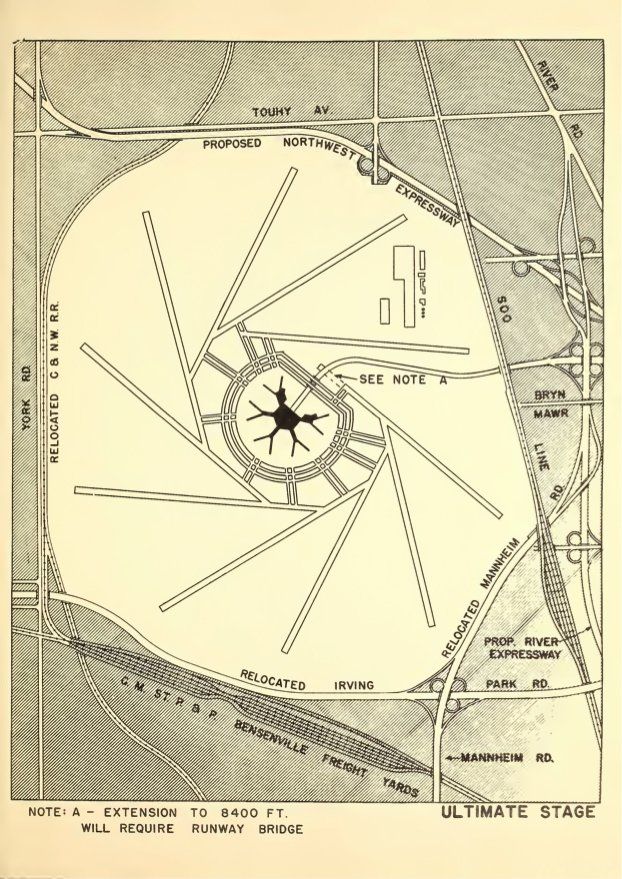

But, it turns out that, all along, there might have been a better way. Better than the crossing runway chaos of the old O’Hare, and better than the boring parallel runways of the new one. Behold, the “Ultimate Stage” of Ralph Burke’s 1948 Master Plan for Orchard “Douglas” Field, the name of the original airport and source of the ORD identifier. It’s a tangential runway masterpiece, a genius idea of elegance and simplicity.

Yes, that’s five sets of parallel runways, each runway 8000-plus feet, all shoehorned into 7500 acres. That’s about one-fifth the size of Denver International, and not a “land and hold short” among them. The unusual pinwheel design not only eliminates crossing runways, but also cures the conflict of intersecting flight paths. Approach controllers would have had a ball throwing airplanes at the airport, especially on a calm wind day. Imagine vectoring to eight or nine final approach courses simultaneously during an arrival push, each airplane touching down far from the terminals, and rolling out immediately into the terminal taxiway structure. OK, so ground control would be a mess, but ground control at O’Hare is always a mess. By the time those airplanes turned around and became a departure rush, the number of landing aircraft would have slowed to at trickle, so you could land any stragglers on just one runway, while flooding the sky with departures off of the other nine. And every departure runway just a short taxi from the gate.

The design has a few conspicuous shortfalls, of course. I mean, were high-speed turnoffs not invented in 1948? And a lot of that space between runways would have to be paved over to create holding areas, because there’d never be enough gate space to accommodate that sort of runway capacity. Uncooperative winds could cut copious amounts from that capacity, as could less-than-ideal weather. As ceilings and visibility lower, the handling of potential go-arounds from the weird runway layout gets persnickety, since “I’ve got visual!” doesn’t work unless the controller can actually see the airplanes.

Usually, separation of a go-around airplane from airborne departures is the problem, but simultaneous go-arounds on converging runways occasionally occur, and when they do, things can get real dicey. Dual go-arounds on runway 4R and (the old) runway 9R at O’Hare caused more controller ulcers than any other configuration, despite the fact that the runways didn’t physically intersect. You had to deal with two airplanes that were low, slow, and not inclined to make any turns for a bit, despite the fact that they were aimed for the same point in space.

The 1948 runway design is packed full of potential for the same type of drama, which points out the one big advantage of today’s multiple parallel runway layout, over both of the older designs: You can run triple and quad approaches in low IFR weather, because the parallel paths protect against adverse outcomes in the event that one (or more) of those arrivals turns into a genuine missed approach.

Alas, according to this piece in Airways News (“The Fascinating History of Chicago’s O’Hare International Airport, 1920-1960”),the tangential runway marvel of ingenuity was never built due to lack of funds. Instead, they built the crossing runway calamity, where a few decades of gap shots and land-and-hold-short ops caused near cardiac arrest for several generations of pilots and controllers, not to mention the collateral costs of delays and lost productivity.

With the price of O’Hare’s latest makeover at $8.7 billion and counting (hey, buying out half of Bensenville wasn’t cheap), had their crystal ball been working, bean counters of the day might have reconsidered and built the thing. I kinda wish they had—it would have been darn fun to work.

Denny Cunningham is a retired tower and ground controller who shot gaps with the best of them at O’Hare for many years. He also a pilot. He lives in Arizona.