Robert M. Robbins was born May 15,1916, in Wilkes-Barre, Pa. He learned how to fly during the summer beforecollege, earned a bachelors degree in aeronautical engineering from MIT in 1938,and went to work for Pan Am as a flight engineer on Boeing 314s. Three yearslater, with only 361 hours as PIC in single-engine aircraft, a private pilotcertificate and no instrument rating, Eddie Allen at Boeing hired him as a testcopilot, and he soon became Eddie’s assistant on the XPBB-1 flying boat program.

Robert M. Robbins was born May 15,1916, in Wilkes-Barre, Pa. He learned how to fly during the summer beforecollege, earned a bachelors degree in aeronautical engineering from MIT in 1938,and went to work for Pan Am as a flight engineer on Boeing 314s. Three yearslater, with only 361 hours as PIC in single-engine aircraft, a private pilotcertificate and no instrument rating, Eddie Allen at Boeing hired him as a testcopilot, and he soon became Eddie’s assistant on the XPBB-1 flying boat program.

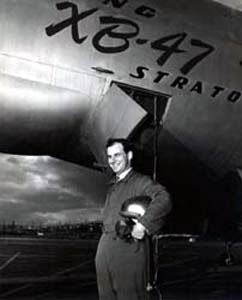

After an in-flight fire in the #2 XB-29 killed Eddie and his crew in February1943, Bob, after an Air Force checkout, took over the #1 XB-29 test program in”The Flying Guinea Pig.” In 1946, Bob was assigned to the XB-47 andwas PIC on its initial flight. In September 1948, Bob retired as a test pilotand became assistant project engineer on the B-47B. In 1956 he was made chiefproject engineer of the Wichita division of Boeing. In 1958 he becameengineering manager of the B-52, and B-52 program manager in 1961. In 1977 hemoved to Daytona Beach as Boeing resident manager at General Electric. Heretired from Boeing on January 1, 1979, at age 62. Bob was a member of theSociety of Experimental Test Pilots and was chairman of its Central U.S. sectionin 1967 and ’68. He’s currently on the Board of Visitors of Embry-RiddleAeronautical University, is a fellow in the American Institute ofAeronautics and Astronautics, and is a member of a number of otheraviation-oriented organizations.

How did you get interested in airplanes?

When I was a kid, about seven or eight years old, I remember laying in bedlooking out my window one night and seeing strange lights off in the distancemoving across the sky. It was an airplane and I was fascinated. Then, like a lotof kids my age, my dad took me to New York for the ticker tape parade tocelebrate Lindbergh’s trans-Atlantic flight. I was permanently hooked! In myfirst year of prep school they asked about plans for the future and goals inlife and I said then that I wanted to be chief engineer of a large aircraftmanufacturing company. I also wanted to learn to fly, but both of my parentswere scared of aviation. My mother encouraged me because it’s what I wanted todo, but my dad put the brakes on. Then, on the night before the day I graduatedfrom prep school, he told me I could learn how to fly … but he didn’t want togive me any financial support. If I was killed, he didn’t want to be a part ofmy death. I learned how to fly in the summer before I went to MIT.

Where did you learn?

In Bloomsburg, Pa., in an Aeronca C-3, with a 36 horsepower two-cylinderengine. It cost six dollars an hour – with or without the instructor. I soloedin about three hours and 40 minutes with no formal ground school – just whatthe instructor would point out as you were walking to the airplane.

I got my private pilot license during my first year at MIT. I’d solicit theguys in the fraternity house on weekends to fly somewhere and split theexpenses. So by the time I got out of MIT, I had about 100 hours in as manydifferent airplanes as I could find. At MIT I had an airplane design course andwe studied an airplane where you had to pull the engine to change the battery.That convinced me that I wasn’t going to be just another theoretical engineer, Iwanted to be a practical engineer.

In 1938, as graduation approached, I was thinking about staying to get amasters degree, but I saw that Pan Am was coming to the campus to interview andI thought I’d see what the interview process was all about. They were planningto start trans-Atlantic operations in the summer of 1939 using BoeingB-314 flying boats, and that sounded like just what I wanted. Getting anaircraft and aircraft engine mechanic’s license and good practical mechanicalexperience and the allure of flying the Atlantic in those big flying boats wasenough for me to abandon the idea of a masters degree, and I went to work forPan Am in June of 1938. My first flight was the ninth trans-Atlantic crossing ofa commercial airplane carrying passengers.

What route did you fly?

North Beach, the seaplane base at La Guardia, had not been built at the time,so we were based in Baltimore and that’s where we did maintenance on theairplanes. We flew the airplane empty from Baltimore to Port Washington on LongIsland to pick up our passengers, because Pan Am could not carry passengersdomestically. From Port Washington we flew to Shediac [New Brunswick], Botwood[Newfoundland], and Foynes [Ireland], and on to Southampton [England]. I onlyflew that route once before September 1, 1939, because Pan Am suspendedoperations to England after Hitler invaded Poland. After that we terminated inFoynes.

Then as winter came we flew a more southern route because of the strongerheadwinds and the chance for ice. The route became Port Washington to Bermuda tothe Azores to Lisbon, and back the same route. Horta, our port in the Azores,was a disaster. By that winter Pan Am had four B-314s in the Atlantic division.Three of them were stuck in Horta over the 1939-1940 Christmas holiday seasonwith their passengers because of the ocean swells. One was there for threeweeks! After that winter Pan Am changed the winter westbound route from Lisbonto Bolama – in Portuguese Guinea on the western tip of Africa – and then toBelem [Brazil] and New York. By then they had finished North Beach at La Guardia.

In February,1941, I was Flight Engineer on the second flight into Bolama. Wemoored the B-314 in the river, and because we were staying overnight we mooredusing the seaplane’s strong bow pendant shackled directly to the heavy anchorchain in case bad weather would come in unexpectedly. The bow pendant is a5/8ths-inch-diameter stainless-steel cable about 15 feet long with one endpermanently attached to the keel about 3 feet underwater. It was a tidewaterriver, and overnight the bow pendant and the anchor chain became badly fouledaround each other and we were unable to separate them from the rowboat we werein. The water was so muddy you couldn’t see a thing. The station mechanic hadcontracted a skin infection and it didn’t seem like a good idea for him to getin the water. So I stripped and jumped in. After several dives, I finally gotthe mess untangled and got back into the rowboat. It was only then that themechanic told me that there were piranhas in the river and only a week earlierthey had attacked a group of native women fishing near shore in water up totheir knees. Before they could get the few feet to shore, the piranhas hadstripped the flesh from their legs. I could have killed that mechanic. That mayhave been the closest I’ve ever come to being killed around an airplane.

How did you get to Boeing?

Bob and #1 XB-29, Nov. 1944 |

In November of 1940, I got a letter from [Boeing Chief of Flight andAerodynamics] Eddie Allen who got my name from MIT. He was looking for flightengineers, flight test engineers, liaison engineers, instrumentation engineers,and a few copilots. I was interested so wrote back with my resume, but I wasabout to be checked out as senior flight engineer at Pan Am, and I wanted thatunder my belt. So I wrote Eddie and laid out the facts and told him I wasn’tready to leave Pan Am, and he wrote back to saying that when I was ready toleave Pan Am I should let them know.

About a year later I was ready to leave Pan Am. I had contacted a few othercompanies and got offers as a flight engineer, but Eddie’s letter had dangledthat word “copilot” and that intrigued me. It turns out that Eddie’sletter had been written by Don Whitworth, who was a flight test engineer thatEddie had hired just three weeks before, and he’s the one who had dangled thatcopilot job in front of me. When Eddie looked at my resume – and by now I had361 hours of single-engine pilot time, a private pilot’s license, no instrumentrating, and I had probably flown 30 different light airplanes, most of themunder 100 horsepower -he wired back that I didn’t have enough experience to bea copilot. I decided to go for broke, and I wired back that I had other offersas a flight engineer, but it was the copilot job that I wanted. It worked. Hewired back the next morning and offered me a copilot job as an engineeringflight test copilot on the B-17. That was the day before Pearl Harbor.

I told my boss, JohnBorger, that I was leaving and he made me a great offer to stay. Theyoffered me the Pan Am training airplane and the instruction I would need to getmy commercial license and a job as a Pan Am pilot. That made the decision a lotharder, and I’m glad I went the way I did, but one of the regrets in my life isthat I wasn’t twins, so I could have taken both opportunities.

Around the middle of ’42 it started to dawn on me why Eddie had probably beenwilling to hire me with so little flight experience. The Boeing plant at Rentonwas being built to build the twin-engine XPBB-1 patrol bomber for the Navy. Sowhile I didn’t have a lot of flying time, I sure had some boat experience fromPan Am. Eddie had picked Bob Dansfield as his assistant for the XB-29, and I wasthe assistant on the flying boat. In the last six months of ’42 I flew about 30hours as copilot on the XPBB-1 with either Eddie or [Boeing Chief Test Pilot] AlReed. Because Eddie had to fly the XB-29 on December 28, 1942, he, withoutwarning, asked me to make the XPBB-1 final demonstration flight for the Navythat day as aircraft commander. It was my first XPBB-1 flight as PIC!

Al Reed left Boeing shortly after Eddie and Bob and their crew were killed inthe crash of XB-29 #2 in February, 1943. The key people who knew my flyingabilities were gone. I had a new boss, (former Chief Project Engineer) N. D.Showalter who had been made chief of flight test. He didn’t know me at all. Afew months later the Navy sent the boat back for some modifications, and N. D.wanted Elliott Merrill – who had never flown the boat – to be pilot and me tobe copilot, but he wanted me to be responsible for the airplane. Elliott was farmore senior, had much more experience, and was a more competent pilot, but noton the boat. I told N. D. – in writing – that I was perfectly willing to becopilot, but that I couldn’t be copilot and be responsible for the airplane. Thecaptain has to make decisions if something happens, and you can’t be responsibleif you’re not the captain. I also told him that Eddie Allen had had enoughconfidence in my ability to let me fly the final demonstration flight for theNavy. I think that forced N. D. to take a good look at me and in the end he mademe the captain for that project, and later assigned me to the XB-29 and theXB-47. That might never have happened if Eddie Allen hadn’t asked me to fly theXPBB-1 final demonstration for the Navy.

Take us through your experience with the XB-47, and the day you outranChuck Yeager.

In the middle of ’46 N. D. Showalter told me Boeing was going to build a jetbomber and asked me to be the flight test representative to the design project.So for about a year Scott Osler, who was to be my copilot, and I learned what wecould about jet airplanes and engines. There were no simulators in those days.We made the first flight on December 17, 1947 from Seattle to Moses Lake. Afterabout three months of testing we had good basic data and we were ready to getprecise performance data. To do that you need a good calibration of the pitot-staticsystem, and the best way to calibrate a big airplane is with a calibrated chaseairplane.

Chuck Yeager & Bob Robbins, 1948 |

So the Air Force sent a chase plane from Muroc – now Edwards – and who arrivesat Moses Lake in a P-80 but Chuck Yeager. He broke the sound barrier in Octoberof ’47, and it still wasn’t widely known, but we knew who he was. I told thisstory at the Gathering of Eaglesat Maxwell AFB in 1997 with Chuck in the second row, and he grinned throughthe whole thing, so I guess I can tell it here. He’s a hell of a nice guy andobviously a very competent pilot but he has two shortcomings in my view: He hasa disdain for civilian test pilots, and contempt for bomber pilots. Outside ofthat, he’s a hell of a nice guy.

We had dinner the night he arrived, then the next morning we both fired upand took off for the test. I gradually increased my speed until I was withinfour or five points of what I thought would be max speed. Then Chuck radioed andsaid “Bob, would you do a 180 and head back to Moses Lake?” I thought,well, he’s smart, he doesn’t have as much fuel as I do and he doesn’t want toget too far from the airport. So I did the 180, got stabilized on speed andaltitude, and Chuck’s not there. I asked where he was and he got on the radioand said “Bob, I can’t stay up with you.” For Chuck Yeager to admitthat he couldn’t stay up with a civilian test pilot flying a bomber is just thejoy of my life!

When did you move from being a test pilot to engineering?

I finished phase one of the XB-47 program, then turned the program over tothe Air Force in July of 1948. Guy Townsend was the Air Force test pilot whoflew phase two. At that point I wasn’t going to be flying, but I’d be there toanswer questions from the ground over the radio. I got into a relaxed mode andrealized that I could keep test flying – which I loved – but way back in prepschool I said that I wanted to be chief engineer of a large aircraftmanufacturing company, and if I was ever going to get back to engineering Iought to start doing it. So N. D. got me a job as me assistant project engineeron the B-47B production program.

Now let me back up a little. About halfway through phase one I was babblingto N.D. about some of the problems with the airplane and he asked me if I hadtold the project about them. I sheepishly said “No, because I don’t knowhow to fix them.” Then N. D. lit into me and said “We’ve got a wholedesign project that knows how to fix things, but they can only do it if theyknow what to fix.” So on his orders I sat down and wrote a five-page memolisting everything that I could think of that ought to be fixed, sent it to theproject, and forgot about it.

Lyle Pierce was the project engineer and I walked into his office on theMonday I was told to report to him and I put out my hand and said “Mr.Pierce, I’m Bob Robbins.” He said “Oh yes, Mr. Robbins, I’ve beenexpecting you. I’ve got a job for you. Fix these!” and he hands me my fivepage memo!

From there it was typical project engineer and program management assignmentsfor the next 30 years. I was assistant project engineer on the B-47B, projectengineer on the B-47C, which was supposed to be the four-engine airplane thatGeneral LeMay was violently opposed to. He didn’t want the B-47 improved toomuch because he didn’t want it to take funds away from the B-52 and he wasafraid that it might even kill the B-52 program. He really wanted the B-52 forthe long haul – and he was right as history has proved.

You played major roles in both the B-29 and the B-47 programs. Whatcontributions did each of them make to history?

They were both so very important. The B-29, along with the two atomic bombs,ended WWII months and maybe years sooner than would have been the case withoutthe B-29. We were planning to begin a full-scale invasion of the Japanese homeislands on November 1, 1945 – just two and a half months after Japansurrendered. The evidence is irrefutable that the Japanese were prepared topowerfully resist such an invasion. There are credible estimates that we shouldexpect a million casualties and the Japanese four million from such an invasion.It was certainly very important to avoid paying such a high price.

First flight of the XB-47 |

On the other hand, the B-47 program made very important contributions in severaldifferent ways that are not widely recognized – probably because the B-47 wasnever in combat, so it gets shortchanged. Because the B-52 was in combat andgets the publicity, it’s often incorrectly considered the granddaddy of today’sjet transports, And that’s just not true. The 35-degree swept wing and much ofthe other technology of today’s jets was on the B-47. The B-52, the KC-135, the707 and the rest of the Boeing 700-series, as well as the Douglas and Airbusseries, started with the B-47’s basic technology. In the 44 years from the timethe Wright Brothers first flew in 1903 until 1947, we gradually worked ourspeeds up to around 340 miles per hour and altitudes to around 24,000 feet.Overnight, in 1947, with the first flight of the XB-47, we had a technology thatmoved those to 600 miles an hour and over 40,000 feet. Today, the engines arebetter, the fuel consumption is better, the size and range of the airplanes ismuch better, but speed, mach number and altitude have improved very little inthe last 53 years.

Many shortcomings were recognized before the XB-47 ever flew and were copedwith in a variety of ways in early XB-47 testing (mostly operating techniques)and with other means in B-47 production – approach and drag chutes, wheelanti-skid systems, vortex generators, etc. Many recognized shortcomings waiteduntil later generations of jets for “good” solutions – engine fuelconsumption, engine acceleration, engine reverse thrust, engine power, wingspoilers for improved lateral control and increased drag and to spoil lift onapproach and after touchdown, etc. But some of the latent B-47 shortcomings werenot recognized until production airplanes had been in service for years.

Most notable were the structural problems that showed up first on thein-service B-47s but were also soon identified as existing on the nextgeneration of jets such as the B-52s, the KC-135s and the C-5As. The solutionsdeveloped during the B-47 program are in clear evidence in today’s jet airplaneindustry. Corrosion control is one, but the major one is coping with thepotential problem of structural fatigue. Huge steel frameworks known as cyclictest fixtures for full-size airframes were first used in the B-47 program. Theyare today an integral part of designing and developing any new large jettransport airplane.

I also think the B-47 may have even prevented World War Three. During theCold War, Russia was really rattling the saber at us with the Berlin blockade,the Korean War, the missiles in Cuba, their huge nuclear bomb program and theirvery aggressive takeover and subjugation of large portions of eastern Europe.There was a lot of fear in this country of a WW III as evidenced by theestablishment of evacuation routes and bomb and fallout shelters. It was prettytense. Some say that General LeMay overdid it and that 2,000-and-some B-47s weremore than we needed, but his philosophy – as I understand it – was todemonstrate power that was so overwhelming that Russia wouldn’t dare attack us.In the 1950s, the B-47 was that power.

[Former National Air & Space Museum Director] Walter Boyne is prettyclear in his writing that the B-47 may have prevented World War III. This andthe technological contributions and heritage from the XB-47 and B-47 programswhich are far broader than most people recognize, make it very difficult for meto choose between the B-29 or B-47 as the more important program. The B-29probably prevented millions of Allied and Japanese casualties. The B-47 may haveprevented even more casualties by preventing WW III. In addition, it certainlyhas changed the world by launching the jet transport age, and technologicallysiring some 20,000 large jet aircraft. Both the B-29 and the B-47 programs werevitally important.

When did you leave Seattle?

The Air Force demanded that the B-47 be built in Wichita. As a result theproduction facilities were initially remote from the experienced B-47engineering design team in Seattle. That leads to delays and communicationproblems, so it was decided to to move an experienced B-47 engineering nucleusfrom Seattle to Wichita to augment the Wichita engineering department. As partof that move I was promoted from Project Engineer on the B-47C in Seattle toSenior Project Engineer on the B-47 production program in Wichita in 1952. Istayed in Wichita until we moved to Florida in 1977.

When you were flying as a test pilot, did you fly general aviation, too?

Only a little bit. During the war general aviation was pretty restricted inthe Seattle area. Right after the war I was part owner of an AT-6. When Istopped professional test flying the middle of 1948, my private life insurancepremiums remained very high. With a wife and two children, I needed that privateinsurance. So to reduce my premiums, I didn’t fly for about 10 years. After 10years, the insurance companies were satisfied that I wasn’t going to be a testpilot any more, so they removed that restriction and I started flying privatelyagain.

What GA airplanes were you flying?

I flew a Boeing flying club Cessna 172, and by then the VOR system had comealong, and I was amazed at how easy navigation had become. Then I bought somestock in a Piper dealership and bought a Twin Comanche, and then Cherokee Sixthat I had for about 15 years. I had it as far north as Point Barrow and as farsouth as Santiago and Buenos Aires. I was doing a lot of flying between Wichitaand Oklahoma City, and Wichita and SAC headquarters in Omaha, and occasionallyDayton and Washington D.C. It was a little slow for the trips east, but thoseextra seats really came in handy for the short hop to Oklahoma City. We usuallyhad people from other departments that needed to go down there, and instead ofit being an overnight trip, we could go down in the morning and get back thesame day. Also, I did some charter flying for the Piper FBO – mostly in a PiperAztec.

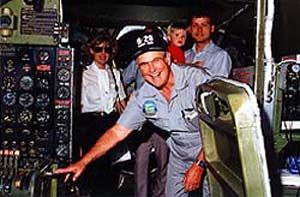

Bob Robbins, the only man to fly the first and the last flying B-29, conducting a cockpit tour of CAF’s B-29 “FIFI” |

How did you get involved with Embry-Riddle?

In 1976 my boss told me we were going to bid to build weapons systemstrainers for B-52s and KC-135s. We would have resident representatives at thefive subcontractors – one in Los Angeles, one in England, General Electric inDaytona Beach – and asked me to think about it. We wouldn’t know for six monthsif we won the contract, but if we won it I’d have a week to decide if I wantedone of those assignments. Daytona Beach appealed to us because I’d thought aboutretiring in Florida. This would be an 18-month assignment, I’d be 62 and a halfwhen it was over, so we thought “why not?”

Once I got to Florida I saw their ads that said “the foremost aviationuniversity in the world.” They’re saying this to a guy who graduated fromMIT, and of course there’s Cal Tech and NYU and University of Washington and Ithought I’d better take a look at that upstart outfit claiming to be theforemost aviation university in the world. I went down and walked the halls, andstuck my head into a couple of the classrooms, and I was favorably impressedwith what I saw. One thing led to another and I was invited to join the Board ofVisitors, then I was chairman of the Board of Visitors for a year, and I’m stillinvolved.

Have you ever taught someone to fly?

I don’t have an instructor’s rating and I’ve never done any formal teaching.One possible exception was in April 1943 when the Air Corps asked Boeing to senda test pilot to their instructor pilot training base at Geiger Field in Spokaneto teach their instructor pilots some of the finer points of flying a B-17.Boeing sent me. At the time I had only 61 hours and 4 month’s experience as aB-17 Aircraft Commander!! Also in the course of our B-17, XPBB-1, B-29 and B-47test flying, I was sometimes teaching very competent copilots about thatparticular airplane – but I never did any formal instructing.

That’s one of the gaps, and another is that I was never in the military.Military training is fantastic and I would love to have had that experience.Rationally I know that I was far more valuable to the war effort doing what Iwas doing as a test pilot but I’ve always felt a little bit guilty about it.General Chidlaw’s comments help greatly to relieve that feeling.

General Chidlaw’s remarks from the posthumous Air Medal award to EddieAllen on April 23, 1946:

… But in the air war there were other men whose work and without whose sacrifice it would not have been possible to get into combat the planes that finally won the war. Especially this was true in the case of the aircraft test pilots – the men who took the planes in their experimental stages, tested their potentialities, ironed out their defects and brought in the reports that made it possible to fashion these airplanes into formidable weapons of war. Theirs was the contribution of a scientific objectivity combined with the daring and fearlessness of the pioneer, and the contribution was a magnificent one. They have earned the admiration and the respect of the men who flew the planes that grew out of their efforts and accomplishments and, as a matter of fact, they were really a part of the great Air Force team that bombed the enemy to defeat.

Bob wrote two chapters about the B-29 and Eddie Allen for ChesterMarshall’s book The Global Twentieth that he has given us permission topublish here.