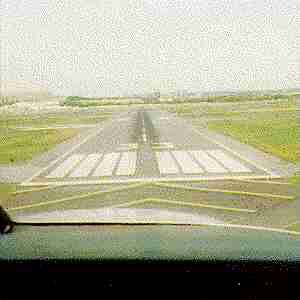

One of the most difficult times in a pilot’s workday is the transitionfrom purely instrument cues to visual cues needed to land froman ILS approach. In my flying career, I have had the misfortuneto see such ham-fisted maneuvers at this critical point that Ithought I would share some ideas on the subject.

One of the most difficult times in a pilot’s workday is the transitionfrom purely instrument cues to visual cues needed to land froman ILS approach. In my flying career, I have had the misfortuneto see such ham-fisted maneuvers at this critical point that Ithought I would share some ideas on the subject.

Transitioning to visual from an ILS is one of those times thatit’s really advantageous to have two pilots in the cockpit. Solet’s start off assuming we have a two-pilot crew; we’ll talkabout single-pilot operations a bit later.

The non-flying pilot

A key concept here is that both pilots—the "flying pilot"and the "non-flying pilot"—we’ll call them FP and NFP—havesignificant roles to play. So whether the NFP is a formal crewmemberor a pilot-buddy of yours who’s just along for the ride, a formalbriefing of the NFP is in order, and should be done well beforecommencing the approach.

A key concept here is that both pilots—the "flying pilot"and the "non-flying pilot"—we’ll call them FP and NFP—havesignificant roles to play. So whether the NFP is a formal crewmemberor a pilot-buddy of yours who’s just along for the ride, a formalbriefing of the NFP is in order, and should be done well beforecommencing the approach.

Among the briefing items must be FAR 91.175(c)(3) that allowsus to continue descent below DH to a height of 100′ above touchdownzone elevation predicated on seeing only the approach lights.It is legal, and properly done, a safety-enhancing method of approachingthe runway. To continue below 100′ above TDZE, you must havethe red terminating or side row bars in sight, or else you mustsee the runway, runway lights, runway threshold, threshold markings,threshold lights, touchdown zone, touchdown zone markings, touchdownzone lights, runway end identifier strobes, or VASI.

Keep it stabilized

A good stablized approach is vital to a good landing when thevisibility is right at minimums. Many regional airlines instructtheir pilots to approach with one flap setting, and once "visual"with the runway, to drop the flaps down to the landing position. What a waste of a good stable approach! While there may be someconcern about aircraft performance on a one-engine go-around,I believe you should avoid such last-minute flap management proceduresthat destabilize the approach right at the most critical moment.

Now assuming you are on-course and on-glideslope as we approachdecision height, the FP should stay on the instruments until specificallytold to look up by the NFP. Why? Because if the FP looks up atDH to look for the lights or runway, a subtle deviation from glidepathwill result. Those seconds spent looking and deciding at DH willalmost certainly make for a poor approach.

So let the NFP tell the FP to continue the descent below DH (onthe gauges) based on seeing the approach lights and sequencedflashers. The FARs say you can legally do this, and it will helpmaintain the trajectory of the aircraft that the FP has been refiningsince the outer marker.

When there is something worth looking at, the NFP can tell theFP to "look up" along with a slight correction like"2 degrees right".

Start to learn how the winds shift at your favorite airports justaround the base of a defined cloud layer or about 300′ above theairport due to surface friction. Be ready for an appropriatecorrection.

Don’t look up at DH

Don’t look up untill the NFP can see either the runway or theapproach lighting system cross bars. I’ll refer to these approachlight cross bars as "the roll bar". Why? Because itis the first visual cue that allows an approximation of a visualhorizon. Take a good look the next time you fly and you can beginto see that you can control the plane with reference to thesebars (and cross check of flight instruments) as your eyes becomeaccustomed to visual flight.

Just trying to fly by looking at the sequenced flashers and stationaryapproach lights will lead you to the runway but most likely leadyou to overcontrol the aircraft until you can establish an outsidehorizon reference. When you have established a visual referencewith the "roll bars" and/or the runway, say "Iam visual" to your NFP. At this point, the NFP should transitionto instruments and verify the flight path.

The NFP should make verbal callouts of deviations from the flightpath or reference airspeed: e.g., "one dot high, airspeeddecreasing." If your ops manual has standard phraseology,use it. If not…CREATE IT! Now is not the time to misunderstanda single word.

Phraseology

I won’t try to give you a new vocabulary, except for the "rollbar". Make one up that works for you. Here’s an exampleof what works for me:

At 1000 feet above touchdown zone elevation:

NFP: One thousand above, checklist complete.

At 500ft above TDZE:

NFP: 500 above, on-course, on-glideslope, Ref plus 5, sinking700, no flags.

If you are off any of these targets, the NFP sould call themout:

NFP: One dot high, one dot left of course, Ref minus 5, sink400.

The NFP should also call out if any flight instruments or navinstruments are not in agreement.

At 100 above dh:

NFP: 100 above, I am going outside.

At dh:

FP: At minimums.

If NFP doesn’t have the approach lights in sight at dh:

NFP: Nothing in sight, go around.

FP: Going around.

If NFP does have the approach lights in sight at dh:

NFP: Approach lights in sight, continue descent.

FP: Continuing descent.

NFP: Roll bar in sight, look up.

FP: Looking up…roll bar in sight…I am visual.

NFP: I am inside.

NFP is now looking at flight instruments, calling flight pathand airspeed deviations, and ready to assist at any time witha go around!

Single-pilot operations

For those of you who fly alone, here are a few ideas you can try:

Verbalize the NFP calls for yourself. Or if you have a trainableright-seat passenger, press him or her into service to make altitudecalls and look for the approach lights.

If autopilot-equipped (and you should be for single-pilotIFR), and if your flight manual permits, let "George"fly a coupled approach and don’t disconnect the autopilot until100′ above TDZE when you have the roll bars or runway in sight.

Stay on the gauges and don’t look up until DH. If you seethe sequenced flashers, go back to the gauges and continue thedescent primarily on instruments to 100′ above TDZE. During thisphase, try moving your eyes quickly between inside and outside,as if you are including the windshield in your instrument scan.Don’t stop scanning the instruments until you’re sure you havesolid visual reference.

Conclusion

The whole idea of this article is for both pilots to work togetheruntil and after solid visual cues have been established by theflying pilot. The decision part of Decision Height can be aidedby the 100′-above-touchdown-zone proviso of the FAR’s based onseeing the sequenced flashers of the approach lights.

Know what to expect from your crewmate—or from yourself, if youare alone in the cockpit. If you have been "on the beam"all the way through to DH, remember not to overcontrol or destabilizethe approach at the last minute.