In-Flight Fire And Impact With Terrain

ValuJet Airlines, Flight 592, DC-9-32

Everglades, Near Miami, Florida

HISTORY OF THE FLIGHT:

On May 11, 1996, at 1413:42 eastern daylight time, aDouglas DC-9 32 crashed into the Everglades about 10 minutes after takeoff from MiamiInternational Airport (MIA), Miami, Florida. airplane, registration number N904VJ, wasbeing operated by ValuJet Airlines, Inc., as flight 592. Both pilots, the three flightattendants, and all 105 passengers were killed. ValuJet passenger records indicated that104 passengers boarded the airplane. A 4-year-old child also was aboard; however, thepresence of this child was not shown on the passenger manifest or on the weight andbalance and performance fawn. Visual meteorological conditions existed in the Miami areaat the time of takeoff. Flight 592, operating under Part 121, was on an IFR flight mandestined for the William B. Hartsfield International Airport (ATL), Atlanta, Georgia.

On May 11, 1996, at 1413:42 eastern daylight time, aDouglas DC-9 32 crashed into the Everglades about 10 minutes after takeoff from MiamiInternational Airport (MIA), Miami, Florida. airplane, registration number N904VJ, wasbeing operated by ValuJet Airlines, Inc., as flight 592. Both pilots, the three flightattendants, and all 105 passengers were killed. ValuJet passenger records indicated that104 passengers boarded the airplane. A 4-year-old child also was aboard; however, thepresence of this child was not shown on the passenger manifest or on the weight andbalance and performance fawn. Visual meteorological conditions existed in the Miami areaat the time of takeoff. Flight 592, operating under Part 121, was on an IFR flight mandestined for the William B. Hartsfield International Airport (ATL), Atlanta, Georgia.

ValuJet flight 591, the flight preceding the accident flight for the same aircraft, wasoperated by the accident crew. Flight 591 was scheduled to depart ATL at 1050 and arrivein MIA at 1235; however, ValuJet’s dispatch records indicated that it actually departedthe gate at 1125 and arrived in MIA at 1310. The delay resulted from unexpectedmaintenance involving the right auxiliary hydraulic pump circuit breaker.

Flight 592 had been scheduled to depart MIA for ATL at 1300. The cruising altitude wasto be flight level 350, with an estimated time en route of one hour 32 minutes. TheValuJet DC-9 weight and balance form completed by the flightcrew for the flight to ATLindicated that the airplane was loaded with 4,109 pounds of cargo (baggage, mail, andcompany-owned material [COMAT]). According to the shipping ticket for the COMAT, itconsisted of two main tires and wheels, a nose tire and wheel, and five boxes that weredescribed as "Oxy Cannisters [sic] – ‘Empty’." According to the ValuJet leadramp agent on duty at the time, he asked the first officer of flight 592 for approval toload the COMAT in the forward cargo compartment, and he showed the first officer theshipping ticket. According to the lead ramp agent, he and the first officer did notdiscuss the notation about the oxygen canisters on the shipping ticket. The ramp agent wholoaded the COMAT into the cargo compartment stated that within five minutes of loading theCOMAT, the forward cargo door was closed. He could not remember how much time elapsedbetween his closing the cargo compartment door and the airplane being pushed back from thegate.

Flight 592 was pushed back from the gate shortly before 1340. According to thetranscript of Air Traffic Control (ATC) radio communications, flight 592 began its taxi torunway 9L about 1344. At 1403:24, ATC cleared the flight for takeoff and the flightcrewacknowledged the clearance. At 1404:24, the flightcrew was instructed by ATC to contactthe north departure controller. At 1404:32, the first officer made initial radio contactwith the departure controller, advising that the airplane was climbing to 5,000 feet. Fourseconds later, the departure controller advised flight 592 to climb and maintain 7,000feet. The first officer acknowledged the transmission.

At 1407:22, the departure controller instructed flight 592 to "turn left headingthree zero zero join the WINCO transition, climb and maintain one six thousand." Thefirst officer acknowledged the transmission. At 1410:03, an unidentified sound wasrecorded on the Cockpit Voice Recorder (CVR), after which the captain remarked, What wasthat?" According to the Flight Data Recorder (FDR), just before the sound, theairplane was at 10,634 feet mean sea level (MSL), 260 knots indicated airspeed (KIAS),andboth engine pressure ratios (EPRs) were 1.84.

At 1410:15, the captain stated, "We got some electrical problem," followedfive seconds later with, We’re losing everything.. At 1410:21, the departure controlleradvised flight 592 to contact Miami Center on frequency 132.45 MHz. At 1410:22, thecaptain stated, We need, we need to go back to Miami,. followed three seconds later byshouts in the background of "fire, fire, fire, fire." At 1410:27, the CVRrecorded a male voice saying, "We’re on fire, we’re on fire."

At 1410:28, the controller again instructed flight 592 to contact Miami Center. At1410:31, the first officer radioed that the flight needed an immediate return to Miami.The controller replied, "Critter five ninety two uh roger turn left heading two sevenzero descend and maintain seven thousand." The first officer acknowledged the headingand altitude. According to a pre-existing agreement between the FAA and ValuJet, airtraffic controllers used the term "Critter" as a callsign when addressingValuJet aircraft. "Critter. referred to the logo of a cartoon airplane painted on theValuJet fleet. The peak altitude value of 10,879 feet MSL was recorded on the FDR at1410:31 and, about 10 seconds later, values consistent with the start of a wings-leveldescent were recorded.

According to the CVR, at 1410:36, the sounds of shouting subsided. About four secondslater, the controller asked flight 592 about the nature of the problem. The CVR recordedthe captain stating "fire" while the first officer radioed, "uh smoke inthe cockp…smoke in the cabin.. The controller responded, "Rogers and instructedflight 592 to turn left when able to a heading of two five zero and to descend andmaintain 5,000 feet. At 1411:12, the CVR recorded a flight attendant shouting,"Completely on fire."

The FDR and radar data indicated that flight 592 began to change heading to a southerlydirection about 1411:20. At 1411:26, the north departure controller advised the controllerat Miami Center that flight 592 was returning to Miami with an emergency. At 1411:37, thefirst officer transmitted that they needed the closest available airport. At 1411:41, thecontroller replied, Critter five ninety two they’re gonna be standing (unintelligible)standing by for you, you can plan runway one two when able direct to Dolphin [VOR] now. At1411:46, the first officer responded that the flight needed radar vectors. At 1411:49, thecontroller instructed flight 592 to turn left heading one four zero. The first officeracknowledged the transmission.

At 1412:45, the controller transmitted, "Critter five ninety two keep the turnaround heading uh one two zero." There was no response from the flightcrew. The lastrecorded FDR data showed the airplane at 7,200 feet MSL, at a speed of 260 KIAS, and on aheading of 218 degrees. At 1412:48, the FDR stopped recording data. The airplane’s radartransponder continued to function; thus, airplane position and altitude data were recordedby ATC after the FDR stopped.

At 1413:18, the departure controller instructed, "Critter five ninety two you canuh turn left heading one zero zero and join the runway one two localized at Miami."Again there was no response. At 1413:27, the controller instructed flight 592 to descendand maintain 3,000 feet. At 1413:37, an unintelligible transmission was intermingled witha transmission from another airplane. No further radio transmissions were received fromflight 592. At 1413:43, the departure controller advised flight 592, "Opa LockaAirport’s about 12 o’clock at 15 miles."

The accident occurred at 1413:42. Ground scars and wreckage scatter indicated that theairplane crashed into the Everglades in a right wing down, nose down attitude. Thelocation of the primary impact crater was approximately 17 miles northwest of MIA.

STATEMENTS OF WITNESSES: Two witnesses fishing from a boat in theEverglades when flight 592 crashed stated that they saw a low-flying airplane in a steepright bank. According to these witnesses, as the right bank angle increased, the nose ofthe airplane dropped and continued downward. The airplane struck the ground in a nearlyvertical attitude. The witnesses described a great explosion, vibration, and a huge cloudof water and smoke. One of them observed, "…the landing gear was up, all theairplane’s parts appeared to be intact, and that aside from the engine smoke, no signs offire were visible."

Two other witnesses who were sightseeing in a private airplane in the area at the timeof the accident provided similar accounts. These two witnesses and the witnesses in theboat, who approached the accident site, described seeing only part of an engine, paper,and other debris scattered around the impact area. One of the witnesses remarked that theairplane seemed to have disappeared upon crashing into the Everglades.

CHEMICAL OXYGEN GENERATORS CARRIED AS CARGO: Events Preceding the Accident:On January 31, 1996, ValuJet agreed to purchase two McDonnell Douglas MD-82s (registrationnumbers N802W and N803W) from McDonnell Douglas Finance Corporation (MDFC), and onFebruary 1, 1996, agreed to purchase a Model MD-83 (N830VV) from MDFC. All three airplaneswere ferried to the Miami maintenance and overhaul facility of the SabreTech Corporationfor various modifications and maintenance functions. SabreTech was a maintenance facilitywith which ValuJet had an ongoing contractual relationship for line and heavy maintenance.

One of the maintenance tasks requested by ValuJet was the inspection of the oxygengenerators on all three airplanes to determine if they had exceeded the allowable servicelife of 12 years from the date of manufacture.

SabreTech determined that all of the generators on N830W had expiration dates of 1998or later, but that the majority of oxygen generators on N802W and N803W were past theirexpiration dates. Because the few oxygen generators on N802W and N803W that had notreached their expiration date were approaching it in the near future, ValuJet directedSabreTech to replace all of the oxygen generators on these two airplanes.

DESCRIPTION OF CHEMICAL OXYGEN GENERATORS: The MD-80 passenger emergency oxygensystem uses chemical oxygen generators together with oxygen masks mounted behind panelsabove or adjacent to passengers. If a decompression occurs, the panels are opened eitherby an automatic pressure switch or by a manual switch, and the mask assemblies arereleased.

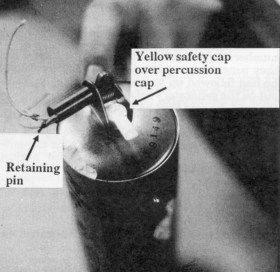

A plastic tube through which the oxygen will flow is connected from the mask assemblyreservoir bag to an outlet fitting on one end of the oxygen generator. Additionally, alanyard, or slim white cord, connects each mask to a pin that restrains the spring-loadedinitiation mechanism (retaining pin). The lanyard and retaining pin are designed such thata one- to four pound pull on the lanyard will remove the pin, which is held in place by aspring-loaded initiation mechanism.

When the retaining pin is removed, the spring loaded initiation mechanism strikes apercussion cap containing a small explosive charge mounted in the end of the oxygengenerator. The percussion cap provides the energy necessary to start a chemical reactionin the generator oxidizer core, which liberates oxygen gas. A protective shipping cap thatprevents mechanical activation of the percussion cap is installed on new generators. Theshipping cap is removed when the oxygen generator has been installed in the airplane andthe final mask drop check has been completed.

The oxidizer core is sodium chlorate which is mixed with less than five percent bariumperoxide and less than one percent potassium perchlorate. The explosives in the percussioncap are a lead styphnate and tetracene mixture.

The chemical reaction is exothermic, which means that it liberates heat as a byproductof the reaction. This causes the exterior surface of the oxygen generator to become veryhot. The maximum temperature of the exterior surface of the oxygen generator duringoperation is limited by McDonnell Douglas specification to 547 degrees F., when thegenerator is operated at an ambient temperature of 70 to 80 degrees F. Manufacturing testdata indicate that when operated during tests, maximum shell temperatures typically reach450 to 500 degrees F.

GUIDELINES FOR REMOVAL OF GENERATORS: Chemical oxygen generator removal andinstallation practices and procedures are contained in the Douglas MD-80 maintenancemanual and on the ValuJet MD-80 work card 0069. The Douglas MD-80 maintenance manualspecifies that non-expended oxygen generators are to be removed from service 12 yearsafter the date of manufacture to maintain reliability in the operation of the generators.According to the generator manufacturer (Scott Aviation), the primary concern that led toestablishing the 12-yearservice life was the continued mechanical integrity of the coreand its support structure, not changes to the chemical composition of the core. The12-year limit was established based on tests conducted by Scott Aviation. ValuJet providedthese documents to SabreTech.

The Douglas MD-80 maintenance manual provides a six-step procedurefor removing the oxygen insert units from the passenger overhead environmental panels.Step 2 of that removal procedure states, "If generator has not been expended, installsafety cap over primer." ValuJet work card 0069 refers to this maintenance manualchapter. Work card 0069 also delineates a seven-step process for removal of a generator.Step 2 states, "If generator has not been expended, install shipping cap [same as asafety cap] on firing pin.n

The Douglas MD-80 maintenance manual provides a six-step procedurefor removing the oxygen insert units from the passenger overhead environmental panels.Step 2 of that removal procedure states, "If generator has not been expended, installsafety cap over primer." ValuJet work card 0069 refers to this maintenance manualchapter. Work card 0069 also delineates a seven-step process for removal of a generator.Step 2 states, "If generator has not been expended, install shipping cap [same as asafety cap] on firing pin.n

Work card 0069 and both relevant chapters of the Douglas MD-80 maintenance manual(chapters 35-22-01 and 35-22-03) contained warnings that generators, when activated,generate case temperatures up to 500 degrees F. The warnings also advised individuals touse extreme caution while handling the generators. Additional warnings in chapter 35-22-01of the Douglas MD-80 maintenance manual call for individuals to "obey theprecautions" and to refer to the applicable material safety data sheet (MSDS) formore precautionary data and approved safety equipment. According to SabreTech, the MSDSfor the Scott Aviation oxygen generator was not on file at SabreTech’s Florida facility atthe time the generators were removed.

Neither the work card nor maintenance manual chapter 35-22-03 (the only maintenancemanual chapter referenced by ValuJet work card 0069) gave instructions on how to storeunexpended generators or dispose of expended canisters.

MAINTENANCE TASKS: About the middle of March 1996, SabreTech crews beganreplacing the expired and near-expired generators with new generators. According to theSabreTech mechanics, almost all of the expired or near-expired oxygen generators removedfrom the two airplanes were placed in cardboard boxes, which were then placed on a rack inthe hangar. However, some of these generators (approximately a dozen) were not put inboxes, but rather were left lying loose on the rack.

According to the mechanics, when an oxygen generator was removed from an insert, agreen SabreTech "Repairable" tag (Form MO21) was attached to the body of thegenerator (although one mechanic stated that he ran out of green tags and put white"Removed/Installed" tags on four to six generators). In the "reason forremoval. section, near the bottom of the green "Repairable. tag, the mechanics madevarious entries such as "outdated," "out of date," and"expired," all indicating that the generators had been removed because of a timelimit or date being exceeded.

Of the approximately 144 oxygen generators removed from N803VV and N802VV,approximately six were reported by mechanics to have been expended. There is no recordindicating that any of the remaining approximately 138 oxygen generators removed fromthese airplanes were expended.

According to the corporate director for quality control and assurance at SabreTech, 72individuals logged about 910 hours against the work tasks described on work card 0069.SabreTech followed no consistent procedure for briefing incoming employees at thebeginning of a new shift, and had no system for tracking which specific tasks wereperformed during each shift.

The mechanic who signed work card 0069 for N802W further stated that he was aware ofthe need for safety caps and had overheard another mechanic who was working with him onthe same task talking to a supervisor about the need for caps. This other mechanic statedin a post accident interview that the supervisor told him that the company did not haveany safety caps available. The supervisor stated in a post accident interview that hisprimary responsibility had been issuing and tracking the jobs on N802W and that he did notwork directly with the generators. He stated that no one, including the mechanics who hadworked on the airplanes, had ever mentioned to him the need for safety caps.

The mechanic who signed work card 0069 for N802W said that some mechanics had discussedusing the safety caps that came with the new generators, but the idea was rejected becausethose caps had to stay on the new generators until the final mask drop check was completedat the end of the process. He also said that he had witnessed both the intentional andaccidental activation of a number oxygen generators and was aware that they generatedconsiderable heat. When asked if he had followed up to see if safety caps had been put onthe generators before the time he signed off the card, he said that he had not.

According to this mechanic, there was a great deal of pressure to complete the work onthe airplanes on time, and the mechanics had been working 12-hour shifts seven days perweek.

The mechanic who signed work card 0069 for N803W stated that he and another mechaniccut the lanyards from the 10 generators that he removed to prevent any accidentaldischarge, and then attached one of the green "Repairable. tags. He stated that hedidn’t put caps on the generators, but placed the generators into the same cardboard tubesfrom which the new ones had been taken. He then placed the cardboard tubes containing theold generators into the box in which the new generators had arrived. He said that heplaced them in the box in the same upright position in which he had found the newgenerators. He said that although he did not see any of the generators discharge, he hadworked with them at a previous employer and was aware that they were dangerous. Thismechanic stated that his lead mechanic instructed him to "go out there and sell thisjob," which the mechanic interpreted as meaning he was to sign the routine andnon-routine work cards and get an inspector to sign the non-routine work card. He said helooked at the work that had been done on N803W, focusing only on the airworthiness of thatairplane.

Of the four individuals who signed the "All Items Signed" block on thesubject ValuJet 0069 routine work cards and the "Accepted By Supervisor. block on theSabreTech non-routine work cards for N802W and N803W, three stated that at the time thegenerators were removed and at the time they signed off on the cards, they were unawarethat the need for safety caps was an issue. However, the SabreTech inspector who signedoff the "Final Inspection. block of the non-routine work card for N802W, said that atthe time he was aware that the generators needed safety caps. He further stated that hebrought this to the attention of the lead mechanic on the floor at the time (but could notrecall who that was), and was told that both the SabreTech supervisor and the ValuJettechnical representative were aware of the problem and that it would be taken care of"in stores," the air carrier’s parts department. According to hire, after beinggiven this reassurance, he signed the card.

SHIPPING: By the first week in May, 1996, most of the expired and near-expiredoxygen generators had been collected in five cardboard boxes. Three of the five boxes weretaken to the ValuJet section of SabreTech’s shipping and receiving hold area by themechanic who said that he had discussed the issue of the lack of safety caps with hissupervisor. According to the mechanic, he took the boxes to the hold area at the requestof either his lead mechanic or supervisor. He said that he placed the boxes on the floor,near one or two other boxes, in front of shelves that held other parts from ValuJetairplanes. He stated that he did not inform anyone in the hold area about the contents ofthe boxes. It could not be positively determined who took the other two boxes to the holdarea.

According to a SabreTech stock clerk, on May 8, he asked the director of logistics,"How about if I close up these boxes and prepare them for shipment to Atlanta. Hestated that the director responded, "Okay, that sounds good to me.. The stock clerkthen reorganized the contents of the five boxes by redistributing the number of generatorsin each box, placing them on their sides end-to-end along the length of the box, andplacing about two to three inches of plastic bubble wrap in the top of each box. He thenclosed the boxes and to each applied a blank SabreTech address label and a ValuJet COMATlabel with the notation "aircraft parts." According to the clerk, the boxesremained next to the shipping table from May 8 until the morning of May 11.

According to the stock clerk, on the morning of May 9 he asked a SabreTech receivingclerk to prepare a shipping ticket for the five boxes of oxygen generators and three DC-9tires (a nosegear tire and two main gear tires). According to the receiving clerk, thestock clerk gave him a piece of paper indicating that he should write "OxygenCanisters – Empty on the shipping ticket. The receiving clerk said that when he filled outthe ticket, he shortened the word "Oxygen" to "Oxy" and then putquotation marks around the word "Empty." He then completed the ticket and putthe date (5/10/96) on the date line at the top of the form. He also said that- afterfinishing the ticket, he was asked to put ValuJet’s Atlanta address on eight pieces ofpaper and to attach one to each of the boxes and tires. The receiving clerk stated thatwhen the stock clerk asked for his assistance, the boxes were already packaged and sealed,and he did not see the contents.

According to the stock clerk, he identified the generators as "empty canisters.because none of the mechanics had talked with him about what they were or what state theywere in, and that he had just found the boxes sitting on the floor of the hold area onemorning. He said he did not know what the items were, and when he saw that they had greentags on them, he assumed that meant they were empty. The stock clerk stated in postaccident interviews that he believed green tags indicated that an item was"unserviceable," and that red tags indicated an item was Beyond economicalrepair" or "scrap.. When asked if he had read the entries in the "Reasonfor Removals block on these tags, he said that he had not.

According to the stock clerk, he weighed the boxes and determined that each one was 45to 50 pounds. He stated he asked a SabreTech driver, once on May 10, and again on themorning of May 11, to take the items listed on the ticket over to the ValuJet ramp area.He said that the driver was busy on May 10, and was not able to load and deliver the itemsuntil May 11.

According to the SabreTech driver, on May 11, the stock clerk told him to take thethree tires and five boxes over to the ValuJet ramp area. He said that he then loaded theitems in his truck, proceeded to the ValuJet ramp area, where he was directed by a ValuJetemployee (ramp agent) to unload the material onto a baggage cart. He put the items on thecart, had the ValuJet employee sign the shipping ticket, and returned to the SabreTechfacility.

According to the ValuJet ramp agents who loaded cargo bins #1 and #2 of the forwardcargo compartment on flight 592, bin #2 was loaded with passenger baggage until full. Bin#1 was loaded with passenger baggage and U.S. mail (62 pounds), which included a mailingtube, a film box, and one priority mail bag. These items were followed by the three tiresand the five cardboard boxes of oxygen generators. According to the lead ramp agent, whoremained outside the airplane when the tires and boxes were loaded, "[the boxes] wereplaced on the side of the tires, facing the cargo door." According to the ramp agentinside the cargo compartment when the boxes were being loaded, "I was stacking theboxes on the top of the tires." The ramp agent testified at the Safety Board’s publichearing that he remembered hearing a "clink. sound when he loaded one of the boxesand that he could feel objects moving inside the box. The ramp agent said that the cargowas not secured, and that the cargo compartment had no means for securing the cargo. Itcould not be determined whether any other items, such as gate checked baggage, weresubsequently loaded into bin #1 before flight 592 departed.

PERSONNEL INFORMATION: The Captain: The captain, age 35, held an airlinetransport pilot (ATP) certificate with an airplane multi-engine land rating and typeratings in the DC-9, B-737, SA-227, and BE-1900. She also held flight instructor, groundinstructor, and ATC tower operator certificates. The captain’s first class medicalcertificate was current with no limitations.

According to company records, the captain had accumulated 8,928 total flight hoursbefore the accident flight, of which 2,116 hours were in the DC-9 and 1,784 hours were asDC-9 PIC.

ValuJet records indicated that on September 23, 1995, while serving as PIC of a ValuJetflight that departed DFVV, the captain experienced an emergency that was later determinedto have involved an overheated air conditioning pack. According to the incident reportfiled by the captain, flight attendants notified the flightcrew of smoke in the cabinshortly after takeoff. The captain stated in her report that the flightcrew could smellsmoke in the cockpit. She stated, "the crew suspected a bleed air problem, but had notime to troubleshoot, since smoke was reported and the threat of a fire existed. It wasfelt Believed] that the safest course of action was to get on the ground as soon aspossible." According to the first officer of that flight, he and the captaindiscussed whether to don their oxygen masks and smoke goggles as they maneuvered todescend and return to the airport. They decided that the situation did not warrant donningthe masks or goggles. According to the first officer, no visible smoke was in the cockpit,although they could smell smoke. The airplane returned safely to DFW.

First Officer: The first officer, age 52, held an ATP certificate with ratingsfor airplane single-engine and multi-engine land, and a type rating in the DC-9. He alsoheld flight engineer and airframe/powerplant (A&P) mechanic certificates issued by theFAA.

The first officer held a restricted FAA first class medical certificate. FAA recordsindicated that the FAA Aeromedical Certification Division was monitoring the first officerfor a self-reported history of diabetes (a disqualifying condition for an unrestrictedmedical certificate). These records also indicated that he was taking the medicationDiabeta, to lower his blood sugar levels.

According to company records, the first officer had accumulated 6,448 total flighthours as a pilot before the accident flight. (His ValuJet employment application alsocited 5,400 hours as a military and civilian flight engineer.) He had 2,148 hours of DC-9experience, including 400 hours as MD-80 international relief captain.

WRECKAGE AND IMPACT INFORMATION: The primary impact area was identified by acrater in the mud and sawgrass. The crater was about 130 feet long and 40 feet wide. Mostof the wreckage debris was located south of the crater in a fan shaped pattern, with somepieces of wreckage found more than 750 feet south of the crater.

The majority of the wreckage was recovered by hand and placed on airboats thattransported the pieces to a nearby levee for decontamination. The pieces were thentransported by enclosed truck to a hangar for examination

The airplane structure was severely fragmented. In general, fewer pieces of right sideforward fuselage skins were identified, and pieces from the right side were generally morefragmented. The majority of identified pieces were from the wing and fuselage aft of thewing box.

Examination of the engines revealed no signs of inflight or preimpact failure.

The tires and wheel assemblies from the landing gear system of the accident wererecovered. The tires exhibited numerous rips and tears. Main landing gear actuators werefound in positions corresponding to retracted landing gear.

The majority of both the left and right wings were recovered.

Most of the right and left horizontal stabilizers were recovered in fragments,including center sections, spars, skin panels, and both hinge fittings. No marks werefound to identify pitch trim or elevator orientation at the time of impact with the swamp.

Several pieces of the rudder were recovered. The largest piece measured 57 inches by 43inches. The preimpact position of the rudder was not determined.

Passenger service units from the cabin were found with the oxygen masks in the stowedpositions.

Three hand-operated fire extinguishers were found, all with severe impact damage.Because of the impact damage, laboratory analysis could not positively determine if theextinguishers had been used.

FORWARD CARGO COMPARTMENT: All recovered wreckage identified as being from thearea of the forward cargo compartment was assembled into a full-scale, three-dimensionalmockup. These pieces included the cargo floor, cargo liners, and fuselage structure. Theyexhibited soot and heat damage.

About 50 percent of the forward bulkhead and about 25 percent of theaft bulkhead of the forward cargo compartment were recovered.

About 50 percent of the forward bulkhead and about 25 percent of theaft bulkhead of the forward cargo compartment were recovered.

Recovered airplane wiring was examined for heat and fire damage and evidence of arcing.Heat and fire damage was observed on many of the wire bundles and cables that ran adjacentto the forward cargo compartment. The heat-damaged wires and cables showed no evidence ofelectrical arcing, and the burn patterns on those wires and cables were consistent withthose resulting from an external heat source.

ANALYSIS: CARGO COMPARTMENT: Although class D cargo compartment are designedaccident and events before this accident illustrate that some cargo, specificallyoxidizers, can generate sufficient oxygen to support combustion in the reduced ventilationenvironment of a class D cargo compartment. The in-flight fire on American Airlines flight132, a DC-9-83, on February 3, 1988, clearly illustrated the need for systems that wouldprovide flightcrews with the means to detect and suppress fires in the cargo compartmentsof airplanes. As a result of its investigation of that accident, the Safety Boardrecommended that the FAA require fire/smoke detection and fire extinguishment systems forall class D cargo compartments. The FAA responded, stating that fire/smoke detection andfire extinguishment systems were not cost beneficial, that it did not believe that thesesystems would provide a significant degree of protection to occupants of airplanes, andthat it had terminated its rulemaking action to require such systems. The Safety Boardconcluded that had the FAA required fire/smoke detection and fire extinguishment systemsin class D cargo compartments, as the Safety Board recommended in 1988, ValuJet flight 592would likely not have crashed. Therefore, the failure of the FAA to require such systemswas causal to this accident.

The crash of ValuJet flight 592 prompted the FAA to state in November, 1996, that itwould issue an NPRM (Notice of Proposed Rulemaking) by the end of the summer of 1997 torequire, on about 2,800 older aircraft, the modification of all class D cargo compartmentsto class C compartments, which are required to have both smoke detection and fireextinguishment systems. The accident also prompted the airline industry group ATA toannounce in December, 1996, that its members would voluntarily retrofit existing class Dcargo compartments with smoke detectors. As of mid-1997, the Safety Board was unaware ofany airplanes that have been modified and are in service.

On June 13, 1997, the FAA issued an NPRM that would require the installation of smokedetection and fire suppression systems in class D cargo compartments. According to theNPRM, the airline industry would have 3 years from the time the rule became final to meetthe new standards. The FAA indicated that it anticipated issuing a final rule by the endof 1997. The Safety Board is disappointed that more than one year after the ValuJet crashand nine years after the American Airlines accident at Nashville, the class D cargocompartments of most passenger airplanes still do not have fire/smoke detection orsuppression equipment and there is no requirement for such equipment. Recent incidents ofcontinued shipment of undeclared hazardous materials, including oxygen generators,highlight the importance of getting the fire safety equipment installed as rapidly aspossible. Therefore, the Safety Board believes that the FAA should expedite finalrulemaking to require smoke detection and fire suppression systems for all class D cargocompartments.

FLIGHTCREW DECISIONS AND ACTIONS: Beginning at 1410:12, the flightcrew noted andverbalized concerns about electrical problems.

Based on the shouts from the passenger cabin recorded by the CVR cockpit areamicrophone at 1410:25 end the comment two seconds later, "we’re on fire, we’re onfire," it should have been clear to both flightcrew members that a very seriousemergency situation existed in the cabin. Although the captain decided immediately toreturn to Miami and initiated a descent, for the next 80 seconds the airplane continued ona northwesterly heading (away from the Miami airport) while the flightcrew accepted ATCvectors for a wide circle to the left and a gradual descent back toward Miami.

The Safety Board evaluated the electrical system, engine, and flight controlmalfunctions that occurred in the 80 seconds during which the airplane continuednorthwestward, away from MIA. The electrical problems that first made the flightcrew awareof the emergency (at 1410:12) likely were the result of insulation burning on wires in thearea of the cargo compartment. Electrical system wiring is routed outside of the cargocompartment of the DC-9, in accordance with federal regulations which require the wiringnot be located against the cargo compartment liner and to incorporate a high temperatureinsulation. Therefore, the flightcrew’s comments about the electrical problems indicatethat the fire had probably already escaped the cargo compartment by 1410:12. (However, itprobably had not yet burned through the cabin floorboards.) The flightcrew commentsrecorded by the CVR from 1410:12 through 1410:22 reflect the pilots’ concerns about andattention to these electrical problems. It is possible that these concerns continued tooccupy some of the pilots’ attention during the initial period of their attempt to returnto the ground.

Another malfunction began at 1410:26, just as the shouts from the cabin would havealerted the flightcrew to the seriousness of the fire there. According to FDR data, whilethe left engine remained at its previous EPR setting, the right engine’s EPR decreased tothe flight idle value. The reduction in thrust would likely have been an intentional actby the flightcrew to reduce power for the descent to return to the ground. The activationof the landing gear warning horn at 1410:28 suggests that the flightcrew had reduced powerto idle (the warning horn is activated by one or both throttle levers being positioned atapproximately the flight idle position). Because the flightcrew would not haveintentionally reduced thrust on one engine only, they must have been unable to reduce thethrust on the left engine because of fire damage to the engine control located above thecompartment. The inability to reduce left engine thrust could have distracted theflightcrew.

Further, the thrust asymmetry continued throughout the period and resulted in asideslip and lateral accelerations that were not corrected with rudder application.Therefore, left-wingdown (LWD) aileron deflections would have been necessary to keep theairplane from rolling to the right. Because there were no right roll indications in theFDR heading data, the flightcrew must have been applying the LWD control inputs.

The FDR indicates that at 1411:20, vertical acceleration increased to about 1.4 G.although the control column had not moved. Subsequently, the control column position wasmoved forward about 5 degrees to reduce the vertical acceleration back to 1 G. At thistime, the airplane leveled temporarily at about 9,500 feet. These events indicate that theflightcrew was confronted with a disruption in pitch control (m the elevator or trimsystems), and was active in maintaining at least partial control of the airplane. Thepilots could have found the disruption in control to be distracting, and the level off isconsistent with their attempts to handle the pitch controls carefully. The development ofmalfunctions from the electrical system to engine thrust controls and flight controlsindicates that the flight experienced a progressive degradation in the airplane’sstructural integrity and flight controls.

At 1412:00, FDR-recorded altitude suddenly decreased and no longer agreed with thealtitudes recorded from radar transponder returns (these altitudes are derived fromdifferent static sources). The disagreement between altitude values indicates that thefire damage continued to increase.

Radar data show that at 1412:58, when the airplane was at 7,400 feet, it began a steeplefiturn toward Miami and a rapid descent. For the next 32 seconds, the descent rateaveraged about 12,000 feet per minute, and the airplane turned from a southwesterlyheading toward the east. If asymmetric thrust were providing right yaw/rolling momentsduring this turn, the flightcrew would have had to counter this tendency with continuingleft roll control inputs throughout the turn. The radar data indicated that the left turnthen stopped on a heading of about 110 degrees at 1413:25, which was toward MIA. Further,the rapid descent rate was being reduced, with the last transponder-reported altitude at900 feet. The control inputs required to balance asymmetric thrust during the steep leftturn, followed by the level-off, indicates that the flightcrew initiated a turn anddescent, and that the captain and/or the first officer were conscious and applying controlinputs to stop the steep left turn and descent (until near 1413:34). Thus, the airplaneremained under at least partial control by the flightcrew for about 3 minutes and 9seconds after 1410:25.

Ground scars show that the airplane was in a large right roll angle and steep nose-downattitude at impact. To achieve that attitude and fly through the position indicated by theprimary radar return at 1413:39, the airplane would have had to start rolling to the rightat 1413:34, at least 8 seconds before the crash.

Because of the lack of evidence from the CVR, FDR, and the wreckage, the Safety Boardwas unable to determine with certainty the reason for the loss of control that occurred atthat time. However, examination of the wreckage showed that before the impact the leftside floor beams melted and collapsed, which would likely have affected the control cableson the captain’s side. It is possible that the first officer might have taken over flyingfrom the captain, but the remaining control cables also were possibly affected bydistorted floor beams. Based on the continuing degradation of flight controls and thedamage to cabin floorboards in the area of the flight controls, the Safety Board concludedthat the loss of control was most likely the result of flight control failure from theextreme heat and structural collapse; however, the Safety Board could not rule outflightcrew incapacitation during the last seven seconds of the flight.

ValuJet emergency procedures for handling smoke and fire uniformly instructed thepilots to put on their oxygen masks and smoke goggles, as the first item to be performedon the emergency checklist. However, the flightcrew comments recorded on the CVR soundedunmuffled. Further, these comments were recorded on the cockpit area microphone channel ofthe CVR; this microphone would not have picked up verbalizations made under an oxygenmask. This indicates that neither the captain nor the first officer donned their oxygenmasks during the period of the emergency in which the CVR was operative and the pilotswere speaking. The last recorded verbalization by the captain was at 1410:49; the last bythe first officer was at 1411:38. Because smoke goggles of the type provided to theflightcrew must be put on after the oxygen mask to have any effect, the pilots probablydid not put on their smoke goggles from the onset of the emergency, at 1410:07, through atleast 1411:38. There is no evidence to indicate whether they donned their masks endgoggles after 1411:38.

The donning of oxygen masks and smoke goggles at the first indication of smoke anywherein the airplane can provide flightcrews with a sustained ability to breath and see in theevent of a subsequent influx of smoke into the cockpit. Although in this accident thedonning of oxygen masks and smoke goggles would not have assisted the crew in the initialstages of the emergency (because of the absence of heavy smoke in the cockpit), earlydonning of the smoke protection equipment might have helped later in the descent, if heavysmoke had entered the cockpit.

In an informal survey conducted by the Safety Board, pilots from several air carriersindicated that they would not don their oxygen masks and smoke goggles for situations suchas reports of a galley fire, smoke in the cabin, or a slight smell of smoke in thecockpit. Based on the circumstances of this accident and the results of its survey, theSafety Board concludes that there is inadequate guidance for air carrier pilots about theneed to don oxygen masks and smoke goggles immediately in the event of a smoke emergency.

Based on the Safety Board’s simulator evaluation of the equipment furnished to theflightcrew of ValuJet flight 592 and its informal survey of air carrier pilots, the Boardconcludes that smoke goggle equipment currently provided on most air carrier transportaircraft requires excessive time, effort, attention, and coordination by the flightcrew toput on. The Safety Board believes that the FAA should establish a performance standard forthe rapid donning of smoke goggles and ensure that all air carriers meet this standardthrough improved smoke goggle equipment, improved flightcrew training, or both.

During its investigation, the Safety Board learned that many current installations ofsmoke goggles at a variety of U.S. air carriers place their goggles within sealed plasticwrapping, and this wrapping is sufficiently thick such that it cannot be easily opened(without using one’s teeth to tear the plastic material or requiring the pilot to obtainand manipulate a sharp object and devote both hands to opening the bag). The Safety Boardis concerned that flightcrews attempting to put on these smoke goggles in an emergencymight be unable to open the wrapping material quickly because the configuration of theequipment requires that the oxygen mask be secured over the pilot’s face before attemptingto don the smoke goggles. The Safety Board concludes that the sealed, plastic wrappingused to store smoke goggles in much of the air carrier industry poses a potential hazardto flight safety.

PROBABLE CAUSE: The National Transportation Safety Board determined that theprobable causes of the accident, which resulted from a fire in the airplane’s class Dcargo compartment that was initiated by the actuation of one or more oxygen generatorsbeing improperly carried as cargo, were: (1) the failure of SabreTech to properly prepare,package, and identify unexpended chemical oxygen generators before presenting them toValuJet for carriage; (2) the failure of ValuJet to properly oversee its contractmaintenance program to ensure compliance with maintenance, maintenance training, andhazardous materials requirements and practices; and (3) the failure of the FederalAviation Administration (FAA) to require smoke detection and fire suppression systems inclass D cargo compartments.

Contributing to the accident was the failure of the FAA to adequately monitor ValuJet’sheavy maintenance programs and responsibilities, including ValuJet’s oversight of itscontractors, and SabreTech’s repair station certificate; the failure of the FAA toadequately respond to prior chemical oxygen generator fires with programs to address thepotential hazards; and ValuJet’s failure to ensure that both ValuJet and contractmaintenance facility employees were aware of the carriers "no-carry" hazardousmaterials policy and had received appropriate hazardous materials training.