What a country, right? In 1960, we were locked toe-to-toe with the Ruskies over who would seize the high ground of space and then the Moon. Sixty years later, three billionaires are checkbook-to-checkbook to see who gets to claim astronaut firsties. And it looks like Amazon impresario Jeff Bezos won’t be the guy.* The cheeky Richard Branson, whose net worth is a measly 3 percent of Bezos’ towering fortune, is currently scheduled to go first on July 11, nine days ahead of Bezos’ launch on July 20.

And thus begins—at least in theory—the age of accessible space tourism. “Accessible” applies here because you’ll recall that another American billionaire named Dennis Tito was the first space tourist, having been launched by those pesky Ruskies in 2001 for a seven-day mission to the International Space Station, which still had that new car smell back then. He reportedly paid $20 million for the privilege and was rewarded with 190 hours in space and 128 orbits. Tito was Yuri Gagarin to Branson’s (and Bezos’) Alan Shepard.

On a per hour basis, Tito got a better deal than Virgin Galactic tourists will. Adjusted for inflation, he paid $160,000 per hour for the experience. We don’t know the precise fare for either Branson’s Virgin Galactic flight experience or Bezos’ Blue Origin, but $250,000 has been widely reported. For the 10- to 15-minute lob to the edge of space, that’s north of a million bucks per hour. One of the seats on the inaugural Blue Origin launch was auctioned for $28 million to an unknown buyer to be announced later.

Blue Origin uses a reusable liquid-fuel rocket with a separable capsule carrying up to six people, although four will be aboard for the July 20 flight, which is considered the first test flight with humans aboard. Virgin Galactic’s system is a high-altitude space plane carried aloft by a purpose-built launch aircraft. Virgin will launch from New Mexico, Blue Origin from the Texas desert 238 miles to the southeast.

Amusingly, dismissing Virgin Galactic as a mere pretender, Blue Origin is adopting the same attitude the Soviets took in 1961 when Shepard’s puny suborbital hop followed Yuri Gagarin’s orbital flight by three weeks: Hardly worthy of mention. The bragging rights turn on which definition of space you choose to accept. The Federation Aeronautique Internationale sets it as the Kármán line, 62 miles (100 km) above the surface and beyond the sensible atmosphere. The FAA and U.S. military define space as 12 miles lower, at 50 miles, and anyone who flies above that can be considered astronauts, according to that definition. “We wish him a great and safe flight,” sniffed Blue Origin CEO Bob Smith to The New York Times last week, “but they’re not flying above the Kármán line and it’s a very different experience.”

Such that many people give the slightest whiff about a billionaire’s astronaut wings, those that do seem unlikely to draw much of a distinction. It’s arguable if an additional 12 miles (72,000 feet) makes the experience an entirely different thing. Either way, if the cabin blows out, you’ll be just as dead just as fast, which segues into the risk these flights represent. It is considerable in systems that haven’t been tested as much as aircraft typically are because there’s no certification template or standard, nor even much of an expectation.

The New Shepard booster has flown 15 times, but zero times with humans. Virgin Galactic has flown even less, with only three powered flights with crews to high altitude. In 2014, it lost one of its test aircraft in a fatal accident attributed to inadequate safety procedures and poor pilot training. While it’s true testing is designed to wring out and fix these flaws, there are always unknowns, especially, as NASA found out by bitter experience, in the interface between the machines and human perception of risk. In other words, hubris.

In defining the risk, George Nield, co-author of a report on space tourism risk, said about 1 percent of human spaceflights have resulted in fatal accidents. “That’s pretty high. It’s about 10,000 times more dangerous than flying on a commercial airliner,” Nield told Business Insider. But what does such a number even mean? It means this: U.S. airlines have achieved a rate of one fatality per 90 million departures. If they operated at a 1 percent fatality incidence, there would be more than 200 fatal accidents … a day. If you plug such numbers into the GA matrix, it would translate to dozens of fatal accidents a day and we couldn’t give away flight training.

If I were betting, I’d say the space tourism industry will do far better than that, but they’ll have to demonstrate it with some data-generating success. Despite the FAA’s insistence that space tourism operate on the informed consent doctrine, the wailing will be something to see after the first accident. We can hope that will never happen while at the same time knowing that it will.

Nonetheless, I’d still fly on one of these programs if someone else were paying for it. I’ve been too long a cheap pilot bastard to think a 15-minute squirt into the thermosphere is worth a quarter of a million bucks. Maybe if my net worth was $50 million, I’d feel differently. So if some wealthy benefactor enthralled with my blogery offered to fund my flight merely to read my galactically inspired prose, which would it be, Virgin or Blue Origin?

Neither. I’d hold out for the third as-yet-unmentioned billionaire Elon Musk’s Space X. This company hasn’t been in a hurry to launch tourists, having been busy developing Mars rockets and orbital capsules and such. But it’s coming, says Musk. To me, space flight is being squashed senseless by launch Gs then slamming into the straps at MECO to find yourself in orbit. Only 553 people have had that unique human experience. It would be worth whatever risk it entails.

How about you? This week’s poll gives you a chance to tell us.

Mercury Rising

While I’m ruminating on space flight, an admission: Although I was 11 at the time, I don’t remember a thing about the national hysteria following John Glenn’s orbital flight on Feb. 20, 1962. I clearly remember Alan Shepard’s flight, especially that shiny pressure suit. And I can picture the grainy video of Gus Grissom’s capsule sinking and hearing newscaster Frank McGee saying the Navy helo pilot gave it “the good old college try” in saving it. That’s the first time I’d heard that expression. But somehow, Glenn got by me.

Although all of us have read in various histories the stunning effect his flight had on the national psyche, a new book called “Mercury Rising: John Glenn, John Kennedy, and the New Battleground of the Cold War” by Jeff Shesol puts Glenn in a more textured context of both the space program and national politics. While it adds detail I was unaware of, it’s neither a complete history of the Mercury program nor a good Glenn biography and in that sense, a bit of a disappointment.

Still, there are nuggets. Although Tom Wolfe brushed past it in “The Right Stuff,” Shesol offers deep detail on how Glenn stood out as a sort of moral guidepost among a mob of car crazies. He drove a dowdy NSU Prinz; the other astronauts had Corvettes. The others also bristled at Glenn’s chiding about after hours extramarital dalliances and the tension it caused threatened the program.

Shesol is unsparing in his description of Glenn’s deep snit for not being picked to fly the first sub-orbital mission, having deemed himself the most qualified and skilled for the job. Glenn was critical of then NASA Manned Spacecraft Center director Bob Gilruth, who controversially allowed the astronauts to fill out a popularity poll to (possibly) pick the first flight candidate. Glenn didn’t top that list and he and Gilruth knew it.

“Mercury Rising” revisits how hurriedly the Mercury program was conceived, how rudimentary it was and how far behind the Russians the U.S. imagined itself to be. (It wasn’t wrong.) While the suborbital flights of Shepard and Grissom put points on the board, everyone knew it was the orbital flight that mattered most. While the author’s lead-in explains why this was so, there’s little satisfying detail about the mission itself.

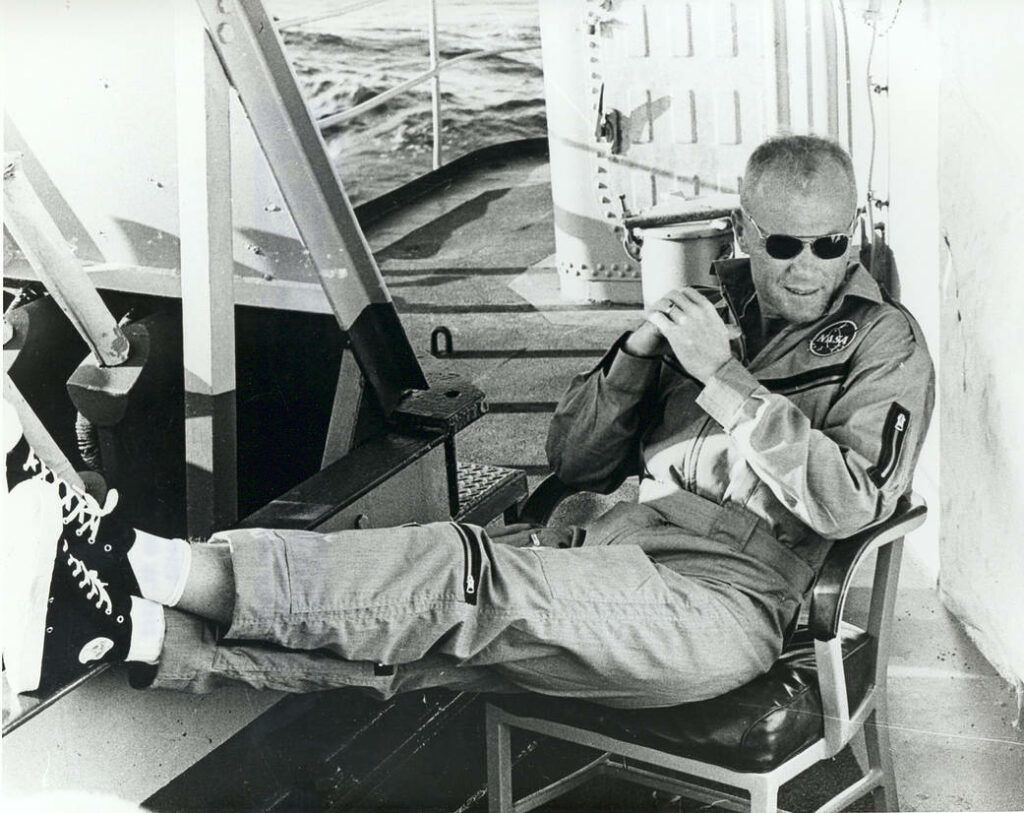

The book reproduces the iconic photograph of Glenn on the recovery ship, the U.S.S. Noa, dictating his mission notes while relaxing in a pair of Converse high tops. The notes were thought to be exhaustive, but missing is a chapter on Glenn’s observations. It would be welcome. One detail Sheshol revealed that I didn’t know about was Glenn’s famous overriding of the balky automatic flight control system.

Even though conceived in the late 1950s, Mercury was planned primarily as a fully automatic spacecraft. At astronaut insistence, manual thruster controls were added in case the pilot had to override the automation. Sure enough, Glenn experienced an apparent automation failure and had to fly manually to keep the spacecraft aligned. But he caused the problem himself. The capsule was programmed to fly blunt end first in case a rapid reentry was necessary and that’s how the autopilot was programmed. But the astronauts wanted the option of flying facing forward, so engineers installed a switch to reverse the stabilization commands. It was added late in his training and Glenn forgot to flip the switch when he pitched the capsule forward. “Crap,” Glenn told the engineers, “I forgot that was there.”

There are enough such observations in “Mercury Rising” to make it worth the reading as an engaging beach book, but a fuller popular history of the Mercury program awaits.

*The Roger Maris asterisk. Space has two definitions.

Paul always includes thought provoking (though sometimes obscure) references in his commentary.

My guess is his reference to the “Roger Maris Asterisk” is in reference to “who had the record for most home runs in one season”—Maris had the record—but the season had been extended—an oblique reference to “which Billionaire will be first in space”—and like baseball, the argument will depend on the original question “where does space begin?”

These indirect references give cause for further examination of the piece for context. Nice work, Paul!👍

It’s just a matter of time before some people and/or institutions inherit a fortune.

I have no problem putting billionaires into space; only with bringing in the back. 😉

Now now, while Branson is a big hypocrite and Bezos does not walk his talk, ….

Paul says he would go into space if someone else is paying. What say we start a Go Fund Me account to cover his trip? Pretty sure we could scrape together a quarter mil and I’ll bet we would all love to read his description of the experience. But, since we really don’t want to lose him, he could choose the time when he is comfortable that the kinks have been worked out. 🙂

Agreed. Why not send a respected and famously objective aviation journalist into space? I’m in for a ten spot.

I always thought the astronauts were just fairly competent pilots who had extra training. They still crashed T38s and like like Glenn, flipped the wrong switch. When we sent the monkey into space he left the automation alone. It is like the Thunderbirds or the Blue Angels, just extra training for the additional risk taken in performances. When the Blue Angels came to my Air Force base we were told to rent them “premium cars”. We got them Thunderbirds. They were not amused.

It depends on which astronauts you’re referring to. Some definitely were top-tier pilots, while others were just above average. But most, if not all, had engineering backgrounds…and could pass a very demanding physical.

I imagine just like everything else, there are great astronauts and decent astronauts. But they are all still human and liable to make mistakes. Even Neil Armstrong made what could be considered a piloting error while flying the X-15.

The story of the BilBoys challenge to mallet-slam their carnival High Striker reminded me again just how thin our atmosphere really is. And our egos, lol. Safe travels to both, but I’ll wait for SpaceX also.

I’d be happy to sit down with Paul for an extended interview after my flight for his expert translation so he could stay safe to write for us for many years to come. And now I’ll snap my fingers and real money will come out of my printer.

But if that doesn’t work, my info for a Go Fund Me account is available upon request.

You could say the same for all aviation now.

Only the rich can fly.

If you mean commercial flight, it’s not outrageously expensive. Owning and flying your own will always have its special hold on one’s time and money.

Rockets are really, REALLY scary things to use for human transportation. Wernher Von Braun reportedly said, “There’s a fine line between a rocket and a bomb…and the finer the line, the better the rocket.”

As far as the FAA/FAI definitions of the start of space, one should also consider the definition used by the international professional astronaut organization… the Association of Space Explorers (www.space-explorers.org). Getting past 50 or 62 miles doesn’t qualify you for membership in the ASE: You have to fly at least one orbit of the Earth.

I’m all for orbit being the criterion, rather than SINO (Space In Name Only) flights that deserve little more than a set of plastic wings such as the used to give kids on airline flights.