Image: Pir6mon

Odds are you remember this from your first intro flight: Shortly after takeoff, the aircraft was rocked by some little burble in the air. If you’re like most people, you turned to the instructor to ask in alarm, “Did I do that?” Later in training, we learned to view bumpy conditions as a potential checkride ally that might persuade a pilot examiner to interpret the published performance standards a little more flexibly. Still later, even “light” turbulence might have posed an obstacle to sharing your love of flight with friends and family.

The fact that you’re reading this article proves that you’re not one of the casualties whose airplanes were broken up in flight by thunderstorms or slammed into ridgelines by mountain waves. But whether it’s life-threatening, alarming or merely annoying, turbulence remains a concern, not the least because it can’t be seen directly and is one of the less-predictable weather hazards. Some situations give all the warning of an irascible drunk trying to pick a bar fight…but even airliners on the high side of 80 tons have had wing skins wrinkled and passengers’ bones broken by jolts that literally arrived out of clear blue skies.

It’s Out There…Maybe.

In the mid-Atlantic states, the warming temperatures of spring are typically accompanied by an AIRMET for “moderate turbulence”— usually from the surface to eight or ten thousand feet—that seems to stay in constant effect from mid-May until at least Halloween. On most of those days, conditions are actually fine, with nothing worse than mild bumps. Occasionally, though, the air gets genuinely unfriendly. Pilots who want to do any flying during daylight hours during that half of the year quickly learn to seek guidance beyond AIRMET Tango, which after all does cover an area of at least 3000 square miles for a six-hour period.

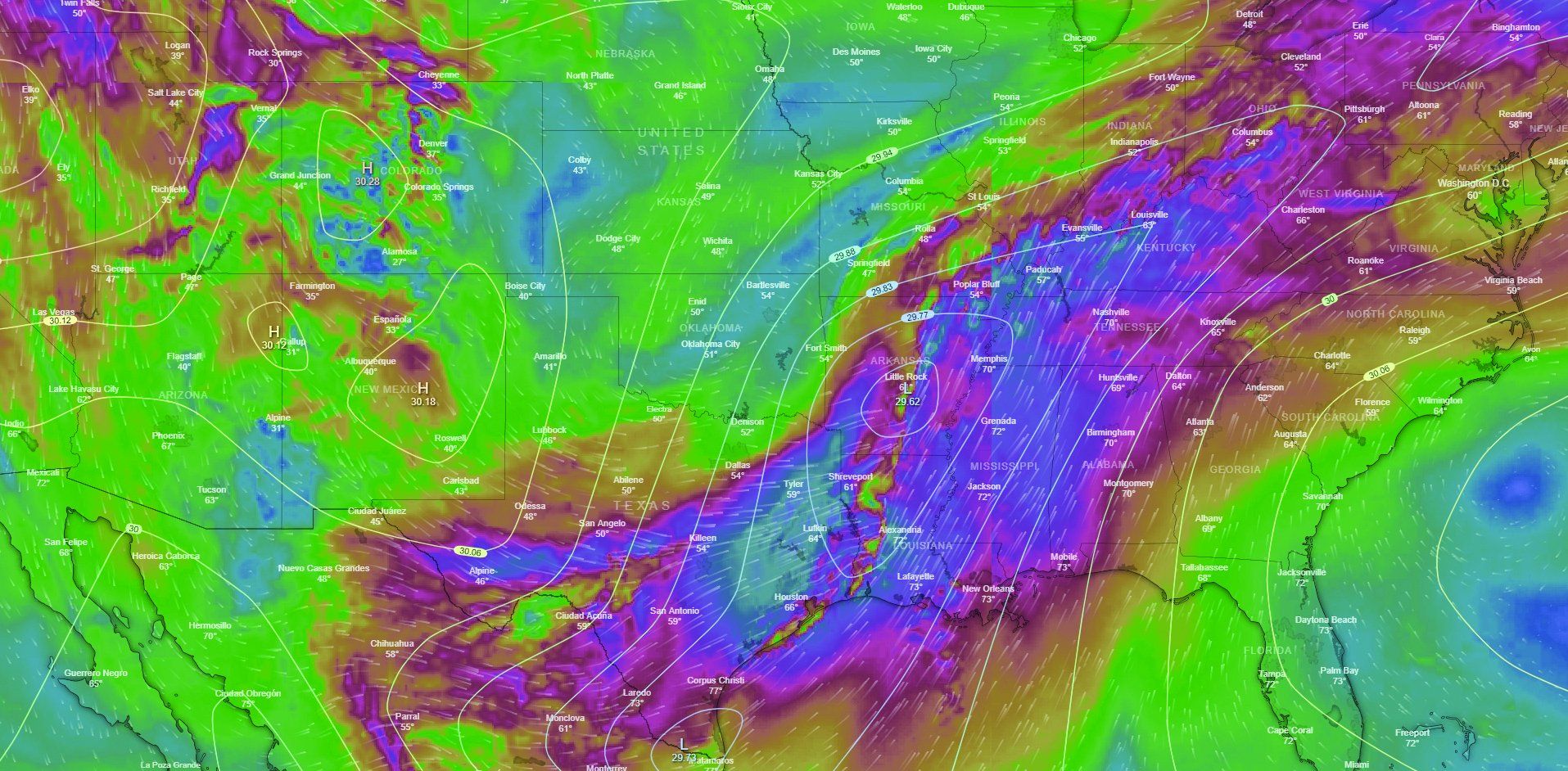

Useful hints come from multiple sources, including prog charts, topographic relief shadings on sectionals, METARs and TAFs. Closely spaced isobars on the prog chart mean a steep pressure gradient, which in turn generates powerful (and often gusty) winds. Strong winds crossing surface irregularities—even ridges as insignificant as the Appalachians’ thousand-foot-high foothills—mean energetic updrafts and downdrafts with all their accompanying turmoil.

In addition to wind speeds and directions, ceilings and visibility are informative in and of themselves: Sunny weather means thermal updrafts, while great visibility suggests unstable air. (Stable layers collect humidity and particulates that increasingly restrict vision the longer they remain undisturbed.) And forecasts of wind shear are clarion warnings of likely nastiness, at least along the boundary layer between quiet and rapidly moving air.

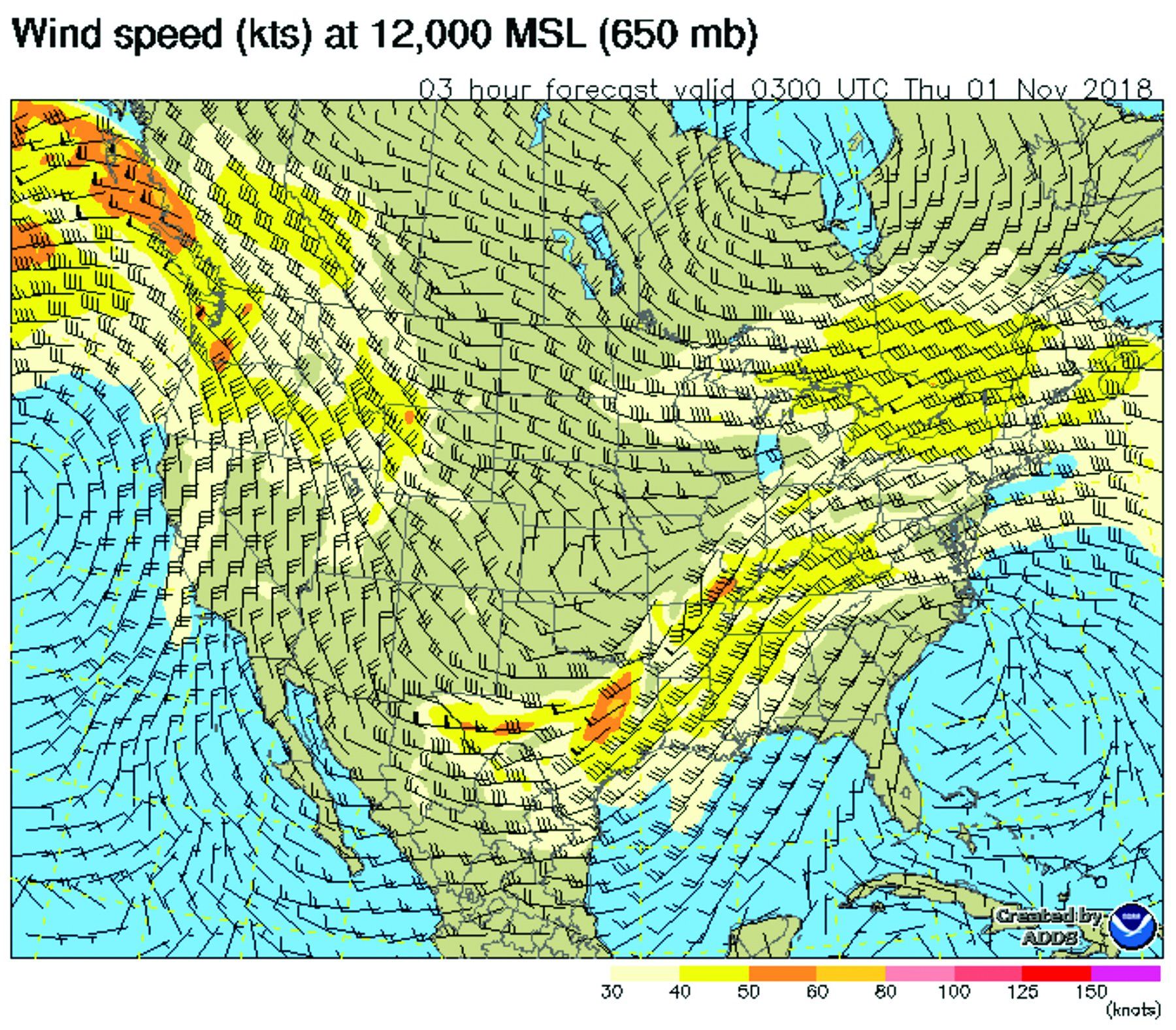

The clear air turbulence that’s been known to wallop airliners is more of a high-altitude phenomenon tied to disruptions of the jet stream, but it’s been known to poke tendrils down into piston altitudes. And mountain waves can propagate hundreds of miles downstream from the mountains in question (although some of the associated roughness often gets scrubbed off en route).

One visible source of extreme disruptions is thunderstorms, from which a healthy buffer is always recommended. Thunderstorm avoidance is a topic that’s generated many well-deserved articles in its own right. Suffice it to say that any detection system other than the Mk. I, Mod. 1 eyeball is subject to potentially catastrophic error. Radar depicts precipitation, not the turbulence that will eventually create it, so towering cumuli building into incipient thunderstorms don’t usually register. And radar images downloaded from datalink are out of date before they arrive due to associated processing, transmission and broadcast delays that can stretch up to 20 minutes. They’re great for identifying areas to avoid but inadequate for navigating in the vicinity of storms.

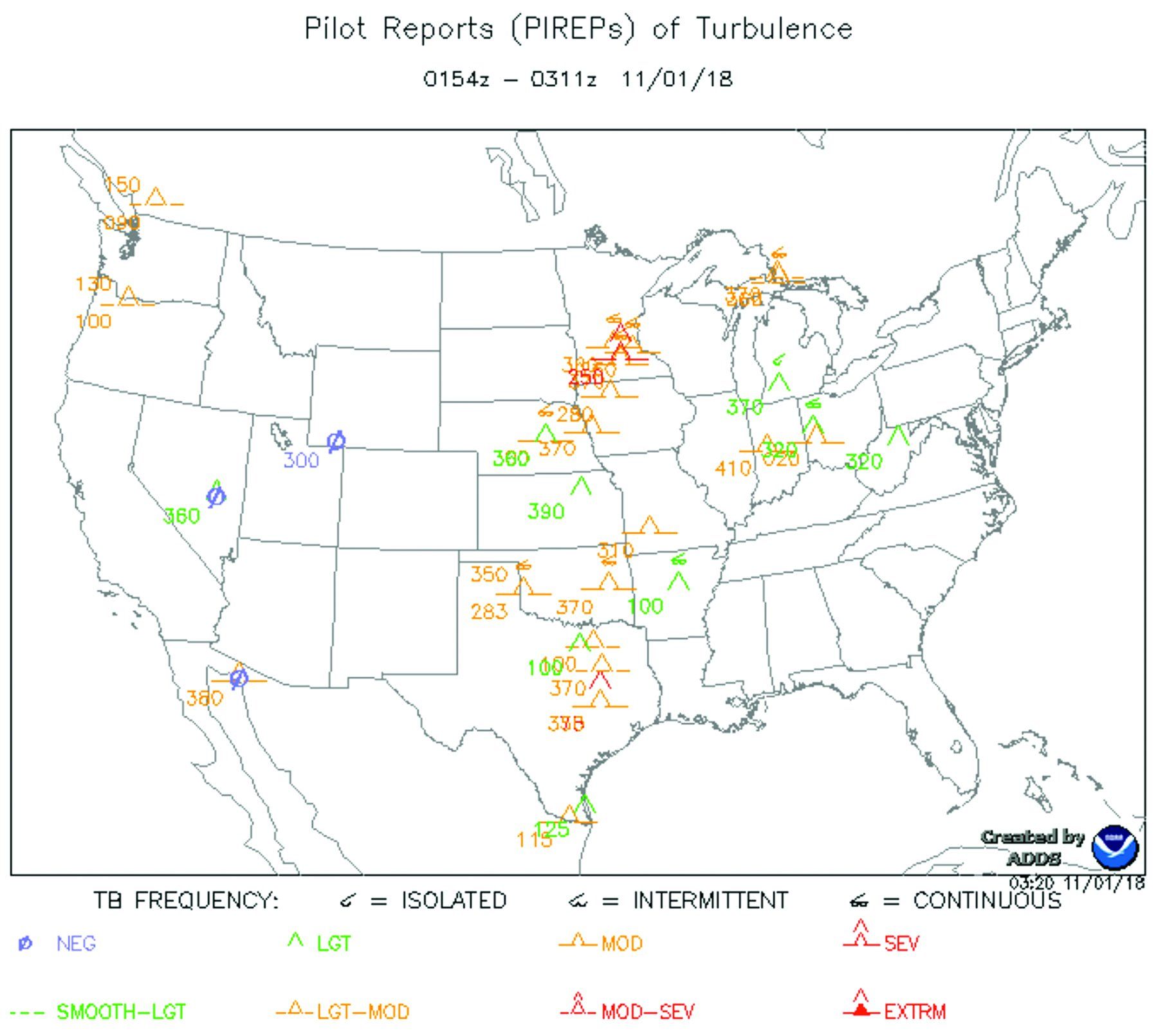

Last but in no way least, PIREPs reflect the actual real-time experience of other pilots operating nearby in the reasonably recent past. These can be your very best friend if someone happens to file one along your route near your proposed time of departure. (Our ongoing favorite is the one that included the comment, “Rough as a stucco bathtub.”) Bear in mind, though, that these are reflections of how one pilot perceived conditions in one place (see “Who’re You Calling ‘Moderate’?” below), conditions that can change quickly over both time and space. The superstitious among us feel that the best way to provoke atmospheric instability is to file a PIREP reporting “negative turbulence.”

Two other considerations can come into play. Forecasting inaccuracies run in both directions. An AIRMET for moderate turbulence doesn’t mean you’ll encounter anything significant, but nor does it guarantee you won’t run into something worse. And the wider the area covered by the AIRMET, the more likely it is that some genuinely rough air will be in there somewhere. (An AIRMET for “moderate to severe”—or worse—is an automatic no-go in our book.) And we’ve found our own tolerance for turbulence atrophies when it isn’t exercised regularly. Bounces that were unremarkable when you flew twice a week can trigger a panic reaction if you haven’t been up in three months. Yes, this tends to improve as you get reacclimated, but as with instrument or crosswind landing skills, it’s best to be realistic about where your comfort zone is right now.

I Still Want To Fly This Year

In aviation as in medicine, prevention is generally preferable to treatment. Since we can’t make the air settle down and behave itself, that translates as avoidance: flying early in the morning or after dark to evade thermal instability, taking the long way around rather than trying to skirt thunderstorms or cross the most rugged line of mountains, and leaving enough time to make alternate arrangements to complete trips that can’t be rescheduled.

Still, the only absolutely sure way to avoid unsettled air is to stay on the ground. Even careful planning and conservative weather judgments don’t guarantee that you’ll never find yourself up in conditions that make you (or your passengers) wish you’d stayed on the ground. Returning in one piece starts with maintaining the calm and focus essential to handling any in-flight emergency.

Getting Out Alive

In a serious turbulence encounter, the most urgent priority is to avoid overstressing the airframe, or at least minimize the extent of the damage. (A Florida flight instructor and his student landed without injury after a thunderstorm encounter on an instrument flight sheared the hinge pins off one door, blew out a passenger-side window and bent the right horizontal stabilizer 30 degrees.) This means minimizing aerodynamic loads, which starts with slowing down—preferably before that first jolt, but if not, as soon as possible afterward. It’s not consistently published for light aircraft, but there is a turbulent air penetration speed—defined as the maximum speed at which gusts won’t cause structural overloads—that’s as much as 20 knots below maneuvering speed. Like VA, it also decreases with aircraft weight; two knots per 100 pounds is a reasonable rule of thumb.

While you’ll want to exit those conditions as expeditiously as possible, remember that gusts momentarily increase your effective airspeed and the corresponding loads. That argues for finding the lowest speed at which the craft can stay aloft. We wouldn’t worry too much about any momentary stalls—the next blast of air will get the wing flying again. Lowering the gear helps to both slow and stabilize retractable-gear airplanes. However, extending flaps is a no-no, since doing so can drastically increase loading and reduce or eliminate the protections offered by flying more slowly.

Even shallow banks impose additional G-loading, so conventional wisdom is to refrain from turning and plow straight on ahead—unless, of course, there’s a chance to turn around before things get too bad. (The Florida instructor attempted a 180 and lost 2000 feet immediately; their Cessna 172 entered the first cell at 8000 feet and escaped the last one at 500.) Fighting the controls also imposes additional loads, so the best practice is generally to forget about maintaining altitude and heading and just try to keep the wings level as best you can. Request a block altitude if you’re IFR, and don’t hesitate to reply “Unable!” as needed—or to declare an emergency.

Calculations change as you get closer to the ground and collision becomes a greater threat. It doesn’t take much contact between a wingtip or tail surface and solid ground to send an airplane cartwheeling. If at all possible, line up a straight-in approach against the wind and come in a little high. If you have to fly the pattern, it’s probably not the time to show how tightly you can space the downwind; give yourself plenty of room to make broad, gentle turns. And if the aircraft’s been damaged to the point that it’s become difficult to control, a precautionary landing off-field may be the best option if you pass any place sufficiently wide and smooth. At that point, all you know is that the airframe’s no longer sound. You don’t know how badly it’s broken or how much longer its pieces will stay together.

With care and just a bit of luck, it’s possible to enjoy a long flying career without ever so much as wrinkling a skin, never mind snapping a spar. But unexpected things do happen, and the first step in escaping is understanding how to avoid making things worse. A prompt reduction in airspeed while avoiding unnecessary maneuvers can be the difference between a hair-raising hangar story and a full-scale NTSB investigation.

Who’re You Calling “Moderate?”

Paragraph 7-1-23 of the FAA’s Aeronautical Information Manual defines the four official levels of turbulence—in terms that are easier to interpret on the sofa than in the cockpit. As a public service, we’ve translated them into Aviator English:

- Light: This isn’t so bad, even if Mom does look a little green.

- Moderate: It’s no fun at all; wrestling the aircraft to keep it right-side up.

- Severe: Even atheists start praying to get down in one piece. It’s how a ping-pong ball feels during a championship match.

- Extreme: Here, the official definition works: “…the aircraft is violently tossed about and is practically impossible to control; it may cause structural damage.”

- There’s also a fifth possibility, “Negative”—the air is buttery smooth.

Worth bearing in mind is that these are subjective impressions on the parts of individual pilots uncorrected for differences in aircraft weight, wing loading and airman experience. A solo student might report “moderate” turbulence in air that his uncle the freight dog considers smooth—while a report of “moderate” turbulence from the flight deck of a Boeing 757 climbing out of Charlotte is a clear indication that it’s not the best day to go up in a Cessna 152.

Avoidance May Be The Best Policy

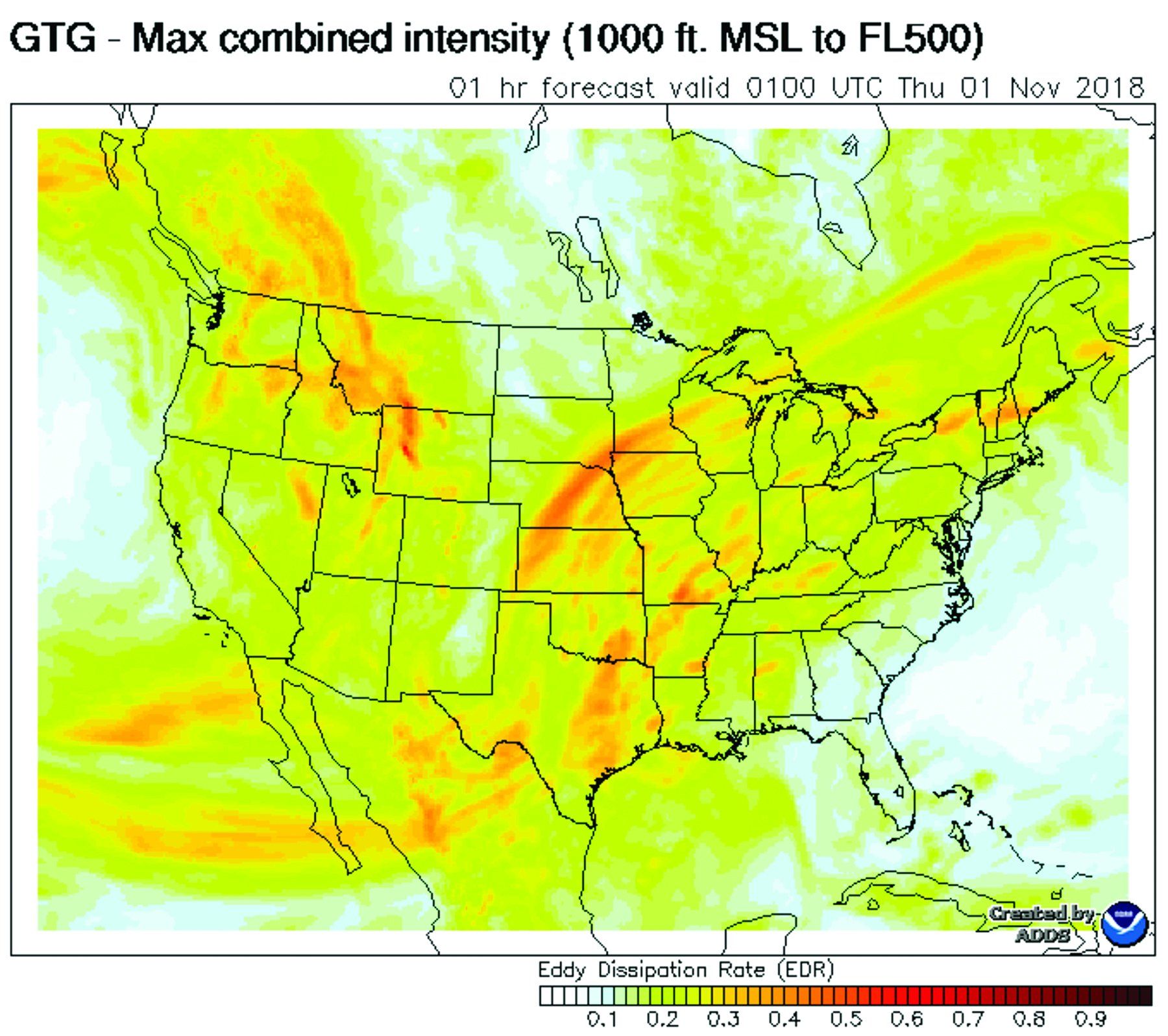

Much of the time, we probably don’t have a lot of choice about where we fly, especially if it’s a short hop. But we often can choose when and, if it’s a long-distance flight, we can change our routing to avoid or minimize the impact turbulence might impose. While in-flight conditions are very much “what you see is what you get,” preflight tools like the ones highlighted here can help us make informed decisions on how we get to our destination.

At top right, the wind contours and barbs forecast where the highest velocity winds will be. Keep in mind the terrain these winds are flowing over. Bottom right, the graphic turbulence guidance, or GTG, provides four-dimensional forecasts of the expected intensity of clear-air turbulence, mountain waves and turbulence generated by terrain and/or thermal sources. The Pireps plot below tells us where turbulence has been reported.

Five Tips For Flying Turbulence

How a pilot properly responds to turbulence depends on the type of bumps being experienced: Dealing with widespread turbulence from summertime thermal activity will be different than coping with mountain waves. Some kinds you may have to live with for a while. If so, consider these checklist items:

- Secure the cabin, including PEDs, pets and people. Not only may dislodged objects injure you, but you don’t want to damage the EFB; you might need it shortly. Tighten your belts.

- Slow. Down. Early. If you’re about to cross a ridge generating a mountain wave or penetrate a building cumulonimbus cloud, don’t wait for the first bumps to decelerate below VA.

- Don’t worry about altitude. Keep the wings level and accept altitude excursions by maintaining an airspeed below your weight-adjusted VA. Use power and landing gear as necessary; stow the flaps.

- Consider a 180. If the turbulence is localized, going back the way you came may be the shortest, quickest and safest way out. Banking increases G-loading, so no steeper than standard rate, please.

- Phone home: As your workload allows, give ATC or Flight Service a PIREP on what you experienced and your position relative to a known fix, the altitude, aircraft type and your intensity estimate.

David Jack Kenny guesses he’s probably not alone in liking smooth air more than it seems to like him. He’s a fixed-wing ATP with commercial privileges for helicopters.

This article originally appeared in the December 2018 issue ofAviation Safetymagazine.

For more great content like this,subscribe toAviation Safety!