Paul Howard Poberezny was born on September14, 1921, in Leavenworth County, Kan. The family soon relocated to the south side ofMilwaukee in a house under an airmail route. Paul grew up watching a stream of biplanesflying low and slow in all kinds of weather. As he got older, he could tell from thesounds overhead that more powerful engines were being introduced to the fleet. The bug hadalready bitten, but it drew blood in May 1927 when Lindbergh landed in Paris. Paul knewthat he wanted to spend his life designing, building and flying airplanes. Paul, now 78,says since age 5 he has said the word "airplane" at least once every day.

Paul Howard Poberezny was born on September14, 1921, in Leavenworth County, Kan. The family soon relocated to the south side ofMilwaukee in a house under an airmail route. Paul grew up watching a stream of biplanesflying low and slow in all kinds of weather. As he got older, he could tell from thesounds overhead that more powerful engines were being introduced to the fleet. The bug hadalready bitten, but it drew blood in May 1927 when Lindbergh landed in Paris. Paul knewthat he wanted to spend his life designing, building and flying airplanes. Paul, now 78,says since age 5 he has said the word "airplane" at least once every day.

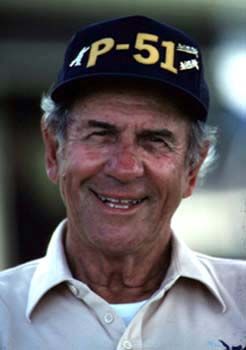

For 30 years he said "airplane, sir" as he served his country as a pilot,flight instructor and mechanic. He holds all seven military pilot wings. The roots of EAAbegan with Paul’s collection of airplane parts from crashes and junked aircraft, which heturned into a museum in the family basement. EAA’s first fly-in was in Milwaukee in 1953.Paul served as president until 1989, when he was named chairman of the board. During thattime, EAA had grown from a basement operation into a worldwide organization with more than100,000 members. Paul has more than 30,000 flight hours in over 400 types of aircraft,including more than 170 homebuilts and 15 of his own design. In his case the apple felldirectly under the tree, since his son Tom is now president of EAA and chairman ofAirVenture. Last Saturday night, July 24, the whole family celebrrated as Paul wasinducted into the National Aviation Hall Of Fame in Dayton, Ohio. We spoke Monday morningas AirVenture ’99 kicked into high gear.

What goes through your mind as you walk around AirVenture Oshkosh and see thousandsof people enjoying themselves?

It’s a wonderful feeling knowing that so many people have been touched by aviation, andnot only my own work but the work of everybody that supported it. So many people havecontributed to the success. The people who led the FAA, and the CAA before that, lovedaviation, and I guess I came upon the scene at the right time with the right people ingovernment. If we tried to start what you see here — EAA and all its chapters around theworld — in today’s society, it would be impossible. The government people in place noware different, society has changed completely, and we just couldn’t do it.

I’ve lived it every day for 46 years so it’s been like watching your kids grow up. If Iwas gone for a while and came back, I’d probably be amazed at how it has grown, but beinghere every day it just seems like all the hard work we’re doing is paying off.

After years in Hales Corners, how did you pick Oshkosh as EAA’s permanent home?

One day I flew around looking for sites. First of all, it had to be close enough toMilwaukee for us to get here and build things and move the exhibits. We were looking atseveral places and I had talked to Steve Wittman about Oshkosh. When I got here I likedhow things were laid out. It had a north/south runway and east/west runway, thesurrounding grounds seemed like what we were looking for, and the community spirit wasbehind it. We presented to the local officials right after there had been a rock concertout here so we had to do a little more talking than we wanted to, but they liked the ideaand they’ve been behind it ever since.

What was the first airplane you saw up close?

One evening, I guess I was about 12, I came home and my mom told me that an airplanehad landed in the fog near our house. I was scared because I had never seen one up close.I looked all over the park and half expected it to jump out and bite me. Then I saw a bigshadow and I walked up very carefully. I walked around and around the airplane until Iwasn’t scared anymore. Then I touched it. Pretty soon I ran home and got a blanket tospread out under the wing. As I lay there in the mist under the airplane, I dreamed aboutlearning how to fly and design and build airplanes. When morning came, I climbed up on thewing and looked at the controls, which I had read about but never seen. Then I had to goto school. Probably the longest day of school in my life. When I got out of school theairplane was gone. The fog had lifted and the pilot had taken off. I’ve often wonderedwhat kind of biplane that was. It wasn’t a Jenny but it did have a water-cooled engine soI think it was an OX-5. Whatever it was, I knew I wanted to learn more about airplanes andflying.

I started sketching airplanes and building models, and one of my teachers, HomerTangney, noticed my interest and made me a deal. One of the Milwaukee flying clubs had aslightly battered Waco glider and he offered to pay for materials if I’d agree to rebuildit. I did rebuild it and flew my first flight in it. I got up to what felt like a hundredfeet but it was only about twenty or thirty. When I pulled the release I made a hardlanding, so I learned right then to keep the nose down. That first flight was from thesame field where I had spent that night under the wing in the fog.

What was the airplane you soloed in?

What was the airplane you soloed in?

Ben White taught me to fly. I soloed in a Porterfield that belonged to the MilwaukeeFlying Club. It wasn’t an easy airplane to fly and it flew pretty blind with that big cowlout front. Then I learned to be a mechanic and a pilot in an OX-5, a World War I airplane.That airplane was my college education.

What was the first airplane you built?

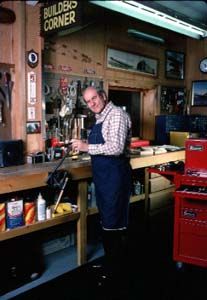

A very much modified clipped-wing Taylorcraft. Then I built "Little Audrey"and the baby Aces. And I’m still building. I’ve got about nine projects going now, alongwith some restorations.

Tell us about your induction into the AviationHall Of Fame in Dayton last Saturday night.

It was a great honor to be with the people who had been enshrined before. We had asellout crowd at the Air Force Museum and it was a crowd that loves aviation like I do, soI talked to them about aviation and the freedoms that it gives us. Most that were therehave had the experience of enjoying the beauty of the earth from the sky. Because of theKennedy news I spoke a little about how we should encourage those in government not tooverreact to every incident that comes along. We want aviation to be safe but there’snothing on earth that guarantees safety in every situation.

I talked a little bit about the aviation industry. Air travel today is not flying, it’stransportation. You don’t see the beauty of the country flying on an airliner lookingsideways out that little window.

There’s a vast untapped ocean of air above us. I say it’s untapped because we don’treally have crowded skies, we have crowded airports. The people that design and buildairplanes never really got together with the people that build runways and terminals, andconsequently air transportation is a lot more inconvinient than it ought to be. I’d liketo see the industry take the lead in informing passengers how they can fly more safely andconveniently. We used to wear fire-resistant flight suits to fly an airplane loaded withjet fuel, and these days people are getting on the airplanes half naked. I think mostairline passengers are ill-equipped to protect themselves from flash fires and otheremergencies. Industry really ought to do this because government is the last resort.

I’ve been lucky enough to have flown 400 types of airplanes over about 30,000 hours andI’m still flying a B-17, a P-51, a Corsair, a Tri-Motor and several others.

I’ve taught many people to fly, the oldest was almost 80. I taught primary to aviationcadets in World War II for about 1,800 hours. I was 19 and a half and all my students wereolder. I never washed any out and I took on some washouts from other classes and got themthrough. I couldn’t believe I was being paid to fly after bagging groceries and pumpinggas.

Why do you suppose you were able to get a washout through when someone else hadgiven up on them?

I always let the students do everything right from the time they get into the cockpit.I always told them, "I already know how to do this — you’re the one that needs tolearn." People imagine that it’s harder than it really is. One of my passions to urgepeople who yearn to fly to take a look over the horizon from an aiplane that they arepiloting.

Maybe I had a little more patience. I was 19 and a half and the other intructors wereolder, so they may have wanted just a few students while I was looking to stay busier. Itook one fellow, Donald Priest, and padded his logbook a little. I gave him about 18 hoursof dual — you were supposed to only get 12 — and got him through. He ended up flyingB-24s in the war. With some people it takes a little more time than others.

(pauses)

In my case, in some ways I’m proud and others maybe not, I can’tspell. I can’t recite the alphabet all the way through. But I keep a daily diary andanybody with a good eighth-grade education could figure out what it says. So you don’thave to be perfect in everything, just be good at what you like to do. I’ve said this manytimes to many audiences but it’s true: No matter what your profession is, if you don’tlove people you’ll never be a success because they won’t follow you.

In my case, in some ways I’m proud and others maybe not, I can’tspell. I can’t recite the alphabet all the way through. But I keep a daily diary andanybody with a good eighth-grade education could figure out what it says. So you don’thave to be perfect in everything, just be good at what you like to do. I’ve said this manytimes to many audiences but it’s true: No matter what your profession is, if you don’tlove people you’ll never be a success because they won’t follow you.

Did you teach Tom or Bonnie how to fly?

No. Tom didn’t learn to fly until later and I was very busy making a living at thattime so we found him an instructor. Same with my daughter. Tom was attracted to thecompetitive side of flying, the sport aviation, and of course flew with Gene Soucy andCharlie Hilliard for 25 years as the Red Devils and the Christen Eagle aerobatic team.Bonnie worked here at EAA for a long time, and now she’s a flight attendant for MidwestExpress.

You raced at Reno for a few years in the ’60s, didn’t you?

I did. I raced the P-51, but racing takes a lot of time. It’s easy to go out in thegarage and build, but racing and travel took a lot of time away from other things. Mymilitary duty took me about 70 hours a week. I did a lot of flying and everywhere I went Iwas the maintenance officer for aircraft maintenance and motor pool, parachutes, radioshops, the whole works. I did most of the functional test flying and also maintained mycombat readiness, and I flew our C-47 for 6,700 hours over 11 years in support of ourunit.

What emergencies stick out in your mind?

I’ve had several interesting rides. Usually you get more scared once you’re on theground and start thinking about it.

Runaway props, jet engines blowing up, hydraulic failures, electrical fires, flightcontrols not responding, just about everything. I took off in a KC-97 tanker, luckily Iwas very light, and lost both engines on one side. I was able to go around and land.

Before World War II I had a lot of forced landings. Airplanes weren’t as reliable backthen. The OX-5 is a good example. I met many a farmer that way. It was an event having anairplane drop into your field. They’d bring you tractor gas and whatever you needed, haveyou up to the house for dinner and tell all the neighbors. These days they’d be calling alawyer about the crop damage before you got out of the airplane.

Society has changed. People complain about the seats in the airliners, about howthey’re too small. Or you can’t use your cell phone in flight. They didn’t have theprivilege of riding in a covered wagon over the Oregon Trail where a good day was if youdidn’t get killed. No rest rooms. No privacy. If the Indians weren’t chasing you, theoutlaws were.

Then I take a load of people up in our Ford Tri-motor. They’re thrilled to get in andwhen we get airborne I look back and see them crowded into those dinky cardboard seatswith three big Pratt & Whitney engines making all that noise. And they’re just ashappy as can be crawling along at a hundred knots.

Tell us about some of the folks you’ve met through aviation.Let’s start with your friend Steve Wittman.

Tell us about some of the folks you’ve met through aviation.Let’s start with your friend Steve Wittman.

(pauses)

I admired Steve when I was a kid. I read about him racing, never expected to get to beclose friends with him. He helped me relocate EAA from Hales Corners to Oshkosh. He gaveme our first race plane, Bonzo, which is in the museum. When he crashed I went to thescene and identified the remains of him and his wife. Then I was involved in theinvestigation of the accident. It was a very sad time. He was a good friend.

I had the privilege of meeting Doug Corrigan, "Wrong Way" Corrigan. He wasquite a character. I was in the military, a major by then, and I flew a T-33 out to LongBeach. I rented a car and drove to his house in Santa Ana. When I pulled up I saw a shortlittle fellow raking leaves. I introduced myself and told him I had polished hisCurtiss-Robbins and he wasn’t that thrilled to see me, until I mentioned that I hadinstructed primary in the 3rd ferry command. Corrigan had been in the 6th ferry commandout of Long Beach and that broke the ice. Now I couldn’t get away. We talked for hours.

I met Mrs. Lindbergh. In 1977, when we built the replica of the Spirit of St. Louis,which is in the museum, I told her about our plans to recognize his flight. I never got areply, which I could understand. We were trying to use her family for a PR thing. But whenwe got the airplane to LaGuardia we called her and asked to stop by the house. She agreedto give us a few minutes.

When we got to her house the grass really needed cutting and I wanted to get out themower and cut it. She wanted no part of that but she served us tea and cookies and talkedfor three hours. Next day she drove up to Hartford and met us at the airport. I was goingto take her for a ride but instead I let Vern Jobst do it. Once she flew in the airplaneshe said, "Now I have a better understanding of my husband." She has now riddenin it three times, and all the children except Jon, who lives in France, have flown in it.

Of course I’ve met most of the astronauts. For me it’s a joy to meet airplane people.Whatever they fly, wherever they live.

Who’s the best stick-and-rudder pilot you’ve ever seen?

Hoover. In fact, he said he thought I was the best he’d ever seen the other night inDayton. He told about the time we were doing F-86 demonstrations in 1954. I had neverheard of him. Well, Bob flew and he did everything great. Then I flew and I went out anddid everything that he did, only I landed shorter than he did. That was because I hadtread showing on my tires after the braking job I did.

I had a reputation as a wild pilot. But the reason I flew like I flew was I wanted tomatch my ability against the ability of the airplane in case I needed to use it in anemergency. One day I was out here approaching [OSH runway] 36 in a B-25 and I had gearproblems. A hydraulic line broke and I had lost all hydraulic fluid. I had enough pressureto get the nose gear down. At first the mains wouldn’t come out of the nacelles, then Iwas able to get the doors open and crank them down into the slipstream. I flew around forabout 90 minutes burning off gas and by then the scanners had picked it up and a linestarted to form. My wife heard about it and came to the airport, too.

I was about ready to pick a place and plunk it into the grass, then I figured I’d tryone more thing. I climbed up and brought it back to about 90 knots to reduce theslipstream. The right one moved, but didn’t lock. On about the fourth try the right onelocked. Now I had a nose and a main, but the left one wouldn’t budge. About that time Iran out of fuel in the right engine, so I told the tower, "Change of plans, I’ve gotabout 12 seconds and I’m coming in."

I touched on the right main, feathered the left engine, cut the mixtures and held theleft wing up, then let the left wing drop and drag into the mud on the side of the runway.Just a little light braking and we were stopped. The damage was a little bit of the leftvertical fin and about 18 inches of left wingtip to repair. We changed the prop, didn’thurt the engine, and two weeks later I flew it to an airshow. That’s the B-25 that’s up inthe museum, by the way.

Well, folks watching this were thinking, "Look at that guy up there doingaerobatics when his gear won’t come down." But I was trying to match my skills to thesituation and it saved the airplane.

There was another stick-and-rudder pilot too. Bob Love. He could do just abouteverything.

What can the average pilot do to become safer and more confident?

Fly as often as possible. Learn about the rudder. Airplanes today don’t need a lot ofrudder except when you get to a low airspeed and you need full deflection of everything toland. Learn to land in different wind conditions. Have the judgement to know when to flyand when not to fly. And know when to turn around.

If you’re not up to the flight that day, polish the airplane.

What’s the greatest innovation you’ve seen in aviation?

The Voyager going around the world in one flight. Having followed that project from thebeginning, and having the Rutans as members of EAA, and visiting their garage inLancaster, California, that was a great achievement to watch.

Have you taken any interesting trips lately on your Harley?

After the show I’m going out west. Wyoming, Montana. I read a lot of western historyand I’ll ride 12 or 14 hours a day then pull over and sleep. I like to pull over once in awhile and lay on a picnic table and if you know the history of a place you can use yourimagination and see all the people that were there.

How important was your wife Audrey to the early days of EAA?

There would be no EAA without Audrey. She was the best-dressedgirl in high school and I was about the worst. My dad made 19 dollars a week pulling acoaster for the WPA, we grew our own food, and we were poor. Audrey and I went togetherfor about five and a half years and I met her dad once. I showed up at her house on an oldmotorcycle and it was the first time I had ever pushed a doorbell. Her dad told me to comeback when I was dry behind the ears, and then he passed away from a heart attack twomonths later.

There would be no EAA without Audrey. She was the best-dressedgirl in high school and I was about the worst. My dad made 19 dollars a week pulling acoaster for the WPA, we grew our own food, and we were poor. Audrey and I went togetherfor about five and a half years and I met her dad once. I showed up at her house on an oldmotorcycle and it was the first time I had ever pushed a doorbell. Her dad told me to comeback when I was dry behind the ears, and then he passed away from a heart attack twomonths later.

Audrey was an only child. She and her mother were very supportive of my work. Audreyworked in the basement for EAA for 11 years without a paycheck. We were saving the moneyso we could build our first facility. Audrey’s mother never missed a day of work at thetelephone company. After work she would help take care of the house so Audrey could helpwith the EAA mail.

The whole family was important to EAA. My daughter Bonnie was licking stamps from thevery beginning, and when she grew up she had several jobs around here. Tom graduated as aNational Honor student in industrial engineering, flew for a while, then about themid-’70s he decided this is what he wanted to do.

Was there ever a time when you didn’t think EAA would make it?

Once. In any organization there are some people who — let’s call it jealousy — andthe problems got to the point where I said "I don’t need this grief" and Ithought maybe we’d shut it down. That was back at Hales Corners. I think it was amisunderstanding that got out of control. I’ve said, EAA has taught me more about peoplethan it has about airplanes.

Then around 1990 some accusations were made about money going into my personalaccounts. That was a real sad time for me after putting in all that time and effort. I’vefound that 98 percent of the people are wonderful, it’s the 2 percent that break up themonotony of life, but I suppose if it weren’t for them it might get boring. We’re past allthat now and things are fine.

I ended up being a millionaire because I have a million friends.