Most pilots I know believe that the Global Positioning System (GPS) is the greatest thing since the invention of DME. It’s easy to see why. It’s like magic. No more pesky VORs; you can navigate direct to any point on the planet. What’s not to like? If you’re a pilot, not much. If you’re a controller, there’s plenty.

Most pilots I know believe that the Global Positioning System (GPS) is the greatest thing since the invention of DME. It’s easy to see why. It’s like magic. No more pesky VORs; you can navigate direct to any point on the planet. What’s not to like? If you’re a pilot, not much. If you’re a controller, there’s plenty.

Around And Around

Do you remember the good old days when airports had names? I do. This was a typical conversation back then: “Hey Atlanta Center, this is Cessna 12345. We’re VFR to Pine Bluff, Arkansas, got time for some advisories?” We’d write down the information, give them a beacon code and ask, “Do you know the identifier for Pine Bluff ?” Nope. Okay. We’d look it up but at least we knew the pilot would be headed west-northwest. We may not know where Pine Bluff is but we know where Arkansas is. Well, most of us do.

Here’s how the conversation goes now: “Atlanta Center, this is Cessna 12345 requesting VFR advisories to eeee, why, eeee.”

We’ll reply, “Cessna 12345, squawk code 2557 and say again your destination.”

“2557, eee, why, eee.”

If we still didn’t understand it, we’d say, “Is that Charlie, Yankee, Bravo?”

“Negative; eee why eee.”

It’s about right here you want to ask if they’ve ever heard of the phonetic alphabet; controllers forget that everyone doesn’t use it every day of the week like we do. There is a good reason to learn it (and use it) though. It tends to save us a three-minute conversation trying to determine that you’re going to Eagle Creek at Indy. Or you could just say you’re going to Eagle Creek, Indianapolis, Indiana and we could dance around in the opposite direction: “Do you know the identifier for Eagle Creek?”

I had a new experience with GPS the other day. Once again it was with a VFR flight requesting advisories. (Editor’s note: This article was originally written in August, 2001.) On initial contact, the aircraft advised me they were “137 miles northeast of Gee Mmm You.” I caught the GMU part right away this time, that wasn’t the problem. Where was I supposed to look? If you measure the distance from GMU on the 025 bearing all the way around to the GMU 075 bearing at 137 miles, you’re covering a really big piece of airspace. So, as I scan from somewhere close to Beckley, W.V., around to somewhere near Liberty, N.C., I see the code.

I had a new experience with GPS the other day. Once again it was with a VFR flight requesting advisories. (Editor’s note: This article was originally written in August, 2001.) On initial contact, the aircraft advised me they were “137 miles northeast of Gee Mmm You.” I caught the GMU part right away this time, that wasn’t the problem. Where was I supposed to look? If you measure the distance from GMU on the 025 bearing all the way around to the GMU 075 bearing at 137 miles, you’re covering a really big piece of airspace. So, as I scan from somewhere close to Beckley, W.V., around to somewhere near Liberty, N.C., I see the code.

“Radar contact five miles northeast of Mount Airy, North Carolina.”

I really shouldn’t do that. I just know one day someone is going to ask me what the identifier for Mount Airy is so they can verify their position on GPS.

A Fine Fix We’re In Now

I hesitate to call anything in ATC a minor inconvenience, since anything that distracts or slows us down can quickly turn into a problem. But all of the above can be called minor when you compare it with GPS in an IFR environment. When you start talking about ensuring separation you had better know to where you are clearing someone. Without reference to any materials (including your GPS), tell me, where is 4330/7130 ? Quickly. That’s the dilemma controllers are faced with a hundred times a day. Is it a right turn or left turn? If it wasn’t such a serious problem, sometimes it’d be hilarious. One time I received a flight plan on the sector with the following for a route of flight: 3545N/8123W..3680N/8013W. That was it. No three letter identifiers, just the LAT/LONGs. I’m serious folks, you can’t make this stuff up. I’m not that creative. Wouldn’t it have been a whole lot easier to file HKY..INT?

If you’re reading this and scratching your head in confusion maybe this will help you understand why all this is important. A few months ago, a controller was working the West Departures out of CLT. Several departures were in a line, climbing out through the departure gate. The controller didn’t recognize the fix filed by the flight in the front of the pack so he did what most Center controllers do in these situations, he used the route function in the computer to draw a line on the radar scope that shows the aircraft’s route of flight. The computer showed a right turn of about 20 degrees. The jet behind that aircraft was to turn slightly left, towards ATL. Great, courses diverge, both aircraft were cleared “on course” and the controller went about his business. The aircraft in front turned about 90 degrees left, into the path of the aircraft behind him. The LAT/LONG in the flight plan was wrong.

If you’re reading this and scratching your head in confusion maybe this will help you understand why all this is important. A few months ago, a controller was working the West Departures out of CLT. Several departures were in a line, climbing out through the departure gate. The controller didn’t recognize the fix filed by the flight in the front of the pack so he did what most Center controllers do in these situations, he used the route function in the computer to draw a line on the radar scope that shows the aircraft’s route of flight. The computer showed a right turn of about 20 degrees. The jet behind that aircraft was to turn slightly left, towards ATL. Great, courses diverge, both aircraft were cleared “on course” and the controller went about his business. The aircraft in front turned about 90 degrees left, into the path of the aircraft behind him. The LAT/LONG in the flight plan was wrong.

But wait, it goes even deeper than that. The center’s computer had assigned the departure gate from CLT based on the erroneous LAT/LONG. The computer didn’t care that the flight plan was to south Georgia by way of Kansas. Humans care, computers don’t. The aircraft should have been routed out the South Departure gate instead of the West Departure gate. I can just imagine the pilot, flying due west out of CLT, shaking his head at the sorry state of ATC, making him fly nearly 90 degrees off-course for 60 miles. Of course, that was probably charitable compared to what he was thinking after being buzzed by a Boeing 737.

The Long And The Lat Of It

Has anyone wondered yet why are there LAT/LONGs in the flight plan? Give yourself a gold star. Here’s why: Your little handheld GPS computer may know virtually every fix in the world but the FAA’s mainframes don’t. Neither do the FAA’s controllers. The FAA’s computers do know LAT/LONGs. The FAA’s controllers don’t. Okay, maybe the oceanic controllers do, but the rest of us don’t. When you file your flight plan from your departure airport direct to your destination airport (or as far as you think you can get away with) and it’s entered into the FAA’s computers, chances are the computer is going to choke on it. It doesn’t recognize a fix. Somewhere, somehow, some person or some machine (it’s a mystery to me) looks up the LAT/LONG for the fix and inserts it into your flight plan. Problem solved. Well, except for that little nagging problem of the controllers not knowing if you’re going north, south, east or west.

I know that DUATS has automated this process. If your flight plan crosses a center boundary, DUATS will put a LAT/LONG in your flight plan. I hope some of you are now asking, “What’s so special about crossing a center boundary?” I’m glad you asked. Read what the Aeronautical Information Manual (AIM) has to say about filing IFR flight plans and see if you can figure it out. (Come on now, I made it through eight paragraphs without referring you to the book. Take a peek.)

I know that DUATS has automated this process. If your flight plan crosses a center boundary, DUATS will put a LAT/LONG in your flight plan. I hope some of you are now asking, “What’s so special about crossing a center boundary?” I’m glad you asked. Read what the Aeronautical Information Manual (AIM) has to say about filing IFR flight plans and see if you can figure it out. (Come on now, I made it through eight paragraphs without referring you to the book. Take a peek.)

For those that took the time to read the entire chapter I hope your brain didn’t explode. I have to admit I gave up on it. But before I did, I picked up a couple of things.

(f) File a minimum of one route description waypoint for each ARTCC through whose area the random route will be flown. These waypoints must be located within 200 NM of the preceding center’s boundary.

Why you are supposed to do that, I don’t know. I’ve heard that it has to do with the center’s computer only communicating with the other center computers that are on its boundaries. Skip one Center and it will mess up the automation. For instance, if you file from a departure point in Atlanta Center (ZTL) to an arrival point somewhere in New York Center’s (ZNY) airspace, skipping Washington Center’s (ZDC) airspace, the flight plan might not pass to ZDC’s computer. How the average pilot is supposed to figure out where each Center’s boundary is, much less where a point “within 200 NM of the preceding center’s boundary” is, I don’t know that either. I guess you’d have to refer to one of those charts that nobody looks at anymore since they got GPS.

You Can Go Your Own Way

Another little gem in that section of the AIM is this one:

d. Area Navigation (RNAV).

1. Random RNAV routes can only be approved in a radar environment. Factors that will be considered by ATC in approving random RNAV routes include the capability to provide radar monitoring and compatibility with traffic volume and flow. ATC will radar monitor each flight, however, navigation on the random RNAV route is the responsibility of the pilot.

You might want to “cut and paste” that paragraph and keep it someplace handy. I assure you that I’ll bring it up again at a later date. I’ll pretend I didn’t see all that other stuff about STARs, transitions, preferred routes, etc., and we’ll move on. If you’re thoroughly confused, just do what you’ve always done and we’ll make it work. That’s what controllers do best, “make it work.”

As I’m writing this article, I am planning a trip to New York. I pull out the map, get a ruler and draw a straight line from my house in Georgia to New York. The first thing I notice is that there isn’t a road that matches my intended route. Forget about all the twists and turns, I have to go either northeast on I-85 to I-95 or I have to turn north at some point, get on I-81 and the cut back east on I-78. I bet it adds 200 miles to my trip, not being able to go in a straight line. Do you suppose if I went out and bought an SUV equipped with GPS I could make my own road? Sounds somewhat silly to be asking doesn’t that, it?

Bear with me while I carry this silly analogy a little further. The route up I-95 is straighter. I think I’ll to go up I-26 to I-81 though, to dodge Charlotte, Washington and every other major metropolitan area along the I-85/I-95 corridor. My route is probably an extra 100 miles, but I won’t be stuck in a traffic jam on the Beltway around Washington, D.C. Are you getting my drift? If you fly up “I-81,” you’ll see some great scenery and talk to some of the friendliest controllers around. Fly up “I-95” and you’ll probably get stuck in a traffic jam. The controllers are just as friendly mind you, they just don’t sound that way when they’re trying to unsnarl the traffic jam.

Our airspace system isn’t quite as structured as the Interstate highway system but the structure we have didn’t disappear with GPS’s invention. It won’t all disappear when GPS becomes universally employed either. I know that the salesman who sold you the GPS unit didn’t tell you that. I know that the proponents of Free Flight don’t like to dwell on that fact. Just another one of the joys of being a Safety Rep. I always seem to be the bearer of bad news.

Boxed-In

Just Another Day At The Office?

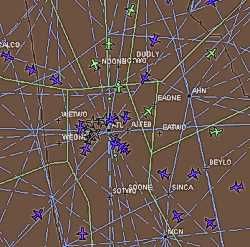

Grab yourself a piece of paper and a pencil. Draw a square box in the middle. Now grab a ruler and make several straight lines that go through the box, on the edge of the box and make sure that you draw several that cut through the corners of the box. Make sure that the lines are “random.”

The box is your sector. You own it. Nothing gets in it, nothing makes a turn inside it or changes altitude without your specific knowledge and approval. Oh, and one extra thing: No one gets within two-and-one-half miles of it without you knowing what they are doing either. Your 2-1/2 miles plus the other sector’s 2-1/2 equals five miles, standard radar separation in the center. Get it? Are you ready? You’re in control. Let’s do it.

The box is your sector. You own it. Nothing gets in it, nothing makes a turn inside it or changes altitude without your specific knowledge and approval. Oh, and one extra thing: No one gets within two-and-one-half miles of it without you knowing what they are doing either. Your 2-1/2 miles plus the other sector’s 2-1/2 equals five miles, standard radar separation in the center. Get it? Are you ready? You’re in control. Let’s do it.

First, take a look at the flight that’s riding the eastern boundary of the sector. Who is working him, you or the other sector? You? Okay, he’s in light chop and wants to descend 1,000 feet. Dial the other sector’s override line and say, “Request control to 15,000 for N12345.” He said approved; give it to the pilot. Now look at the route that cuts through the southwest corner of your sector. He’s only going to be in your sector for three miles so you are going to get a “point out” on the flight. It goes like this: As you are telling N12345 “descend and maintain one-five thousand,” you hear a BEEP in your headset. “Go ahead override.” You hear, “Point out, ten miles northwest of Volunteer, N23456, direct Savannah at one-seven thousand.” You don’t have any conflicting traffic so you say, “Point out approved.” Now you don’t have to talk to that airplane and you can just watch him go by. Cool huh? We’ll see. You did listen to the readback from N12345 didn’t you? Okay.

See that flight that’s going right through the middle of your sector? His climb rate dropped off and now he’s not going to make it into the high sector’s altitudes before he crosses your northern horizontal boundary. You’re going to have to point him out. Now keep in mind that you’ll be talking to another facility. They don’t have a full data block to look for and you can’t use the override line. Here we go.

“London six eight line, point out.” No answer. “London six eight line.” (The theme song from final “Jeopardy” plays through your mind.) “London six eight line.”

“This is London, go ahead.”

You say, “Point out thirty northeast of Volunteer, code five two one three, out of flight level one niner zero, climbing high.”

The London controller asks, “What kind is he?”

You look at the flight progress strip and reply, “A regional jet climbing slow.” He says, “Traffic, stop him off at flight level two two zero and put him on me, radar contact.”

“Center, this is N12345, we’re still in the chop – can we descend down to (BEEP) fourteen thousand?”

“Standby override.”

“N12345, stand by. Commuter five eighty-three amend altitude, maintain flight level two two zero.”

“BLOCKED.”

“Commuter five eighty-three, amend altitude, maintain flight level two two zero.”

“Commuter five eighty-three, okay, two two zero, can we get direct SWEED?”

You ignore the request and say, “Go ahead override.”

“This is LOGEN, request N23456 twenty degrees left for traffic.”

You say, “It’ll take me a second, I took a point out.”

That’s not his problem and he says, “Whatever, I need him twenty left.”

With a sigh you say, “Okay.” You call the previous sector on the override and ask them to turn N23456 20 degrees left as you hear in the speaker another aircraft calling and at the same moment you hear in the other speaker, “HEY ATLANTA I NEED TO TALK TO COMMUTER 583 RIGHT NOW!!!”

Are we having fun yet? So far you’ve made two transmissions (that weren’t blocked), received two phone calls and made two phone calls. You’re so far behind the power curve that other controllers are yelling at you, somebody else (you don’t have any idea who) called that you haven’t answered yet and poor old N12345 is still in the chop. Before you can move him you’ve got to make yet another call. Once you make that call (praying that no one else calls on the radio at the same time) you’ve got to get back on the frequency and say, “Calling Atlanta say again, I was on the landline.” You’d better answer N12345 before you do that or he and the unknown will step on each other. Keep in mind that all the pilots have heard is two transmissions. The frequency isn’t busy so you can’t be busy. Right?

Are we having fun yet? So far you’ve made two transmissions (that weren’t blocked), received two phone calls and made two phone calls. You’re so far behind the power curve that other controllers are yelling at you, somebody else (you don’t have any idea who) called that you haven’t answered yet and poor old N12345 is still in the chop. Before you can move him you’ve got to make yet another call. Once you make that call (praying that no one else calls on the radio at the same time) you’ve got to get back on the frequency and say, “Calling Atlanta say again, I was on the landline.” You’d better answer N12345 before you do that or he and the unknown will step on each other. Keep in mind that all the pilots have heard is two transmissions. The frequency isn’t busy so you can’t be busy. Right?

The Moral

What’s this got to do with GPS? Everything. The sector boundaries were designed around the VORs and the airways to handle the major traffic flows that were on the same airways.. That kept coordination down to a minimum. Aircraft on the airways were firmly inside your sector except for the few moments (five miles, remember?) it took to cross a sector boundary. Now that GPS/random routes have made those boundaries obsolete, the amount of coordination has gone through the roof. You’d be absolutely amazed (I know I am) how many times an aircraft’s path rides the border of a sector or goes through the corner where four sectors meet. I’m beginning to think that the phone company invented GPS. Sometimes I spend more time on the phone coordinating with other controllers than I do talking on the radio to pilots.

Whose Side Are You On, Anyway?

I once had an actual face-to-face conversation with a pilot that was at the end of his rope. He felt he was getting jerked around every time he flew his regular route from HKY to CRE and back. It was never the same way twice. From all the stories he was telling me I couldn’t figure out what he was doing wrong. We pulled out the map, drew the straight line and the problem leapt out at me. His route of flight went right through the corner where Atlanta Center (ZTL), Washington Center (ZDC) and Jacksonville Center (ZJX) meet. For good measure, it’s also the exact place that three approach controls meet.

As hard as it is for controllers to coordinate around a border it’s virtually impossible for the computers. As far as the computer is concerned, you’re either in my airspace or you’re in the other guy’s airspace. You’re not in both (even if you are). In this case, we’ll say the computer processed his route of flight from ZTL’s airspace (computer) to ZJX’s airspace (computer). If for any reason (weather deviation, vector for traffic) this flight winds up a few miles east of where the computer thinks it should be, the airplane may enter ZDC’s airspace (or the corresponding approach control’s) but the flight-plan data won’t.

As hard as it is for controllers to coordinate around a border it’s virtually impossible for the computers. As far as the computer is concerned, you’re either in my airspace or you’re in the other guy’s airspace. You’re not in both (even if you are). In this case, we’ll say the computer processed his route of flight from ZTL’s airspace (computer) to ZJX’s airspace (computer). If for any reason (weather deviation, vector for traffic) this flight winds up a few miles east of where the computer thinks it should be, the airplane may enter ZDC’s airspace (or the corresponding approach control’s) but the flight-plan data won’t.

Depending on what individual was working the aircraft, other traffic, which way the wind is blowing or any number of factors, the pilot was being vectored back to where the computer thought he should be, being asked a dozen questions when a facility discovered they didn’t have any flight-plan data and/or working with a different facility every time he took the trip. In short, he felt he was being jerked around. When in fact, he was a victim of his technology. You could say he was a victim of the FAA’s lack of technology if you want, but I haven’t figured out how to make a “random” boundary. If you think you can make a random boundary, test out the theory with your neighbors and let me know how it works out.

Gesundheit!

Enough of this en route stuff. Let’s talk GPS approaches. And you thought the FAA didn’t have a sense of humor…

“Hey center, N12345, how about direct DUXZU?”

“Bless you N12345; where did you want to go? “

“DUXZU”

“Maybe you’d better go see a doctor that sounds like a nasty cold.”

“No center, we want to go direct DUXZU, the initial approach fix for the GPS RWY 28 at Mount Airy.”

(It’s a good thing he didn’t ask for direct ADQAJ or we would have thought he was choking on something.)

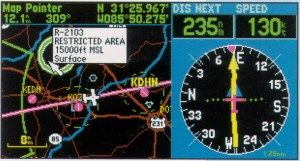

Among the multitude of problems center controllers are having with GPS approaches is our lack of familiarity with them. The ILS and NDB approaches are shown on the radar scopes. We have a symbol right on the glass depicting the NDB and the airport. If we can vector for the final approach course (FAC), we will have a line depicting the FAC on the glass, too. In contrast, none of the fixes are depicted for the GPS approaches: at least not in my Area of Atlanta Center.

Among the multitude of problems center controllers are having with GPS approaches is our lack of familiarity with them. The ILS and NDB approaches are shown on the radar scopes. We have a symbol right on the glass depicting the NDB and the airport. If we can vector for the final approach course (FAC), we will have a line depicting the FAC on the glass, too. In contrast, none of the fixes are depicted for the GPS approaches: at least not in my Area of Atlanta Center.

If you come on my frequency and request direct ALDOH for the GPS RWY 10 at SVH, you’ll probably get the response, “Uhhhhhhh … standby.” I’ll pull out the chart, find ALDOH and the first thing I’ll wonder is, “Is that even in my airspace or is it CLT’s?” I’ll have to ask the computer (assuming the computer knows it) where it is and see if I need to coordinate with CLT to use their airspace. If I do, the first question the CLT controller is going to ask is, “Where the heck is ALDOH?” And yes, you guessed it, when we’re done with that long-winded conversation, we’ll have to get back on the radio and say once again, “Say again, I was on the landline.”

It will take us a while to become as familiar with the GPS approaches as we are with the other instrument approaches. Please be patient. If you’re going to ask for direct to a fix on a GPS approach, please make sure it’s a fix designated as an initial approach fix (IAF). You can’t start the approach from an intermediate fix. We can’t vector for the FAC of a GPS approach either. Your mileage may vary at other facilities.

The Center Approach

While we are on the subject of instrument approaches, let me get just a little off the GPS subject. Most controllers who work in the centers east of the Mississippi aren’t that familiar with instrument approaches. You’ll run into some areas like mine that provide approach control services on a full-time basis, but you’ll run into more like the area just south of mine where the controllers don’t work any airspace below 11,000, except on the midnight shift, when the center assumes control of a lot of airspace when a local approach control closes for the night.

As a pilot, it would be worthwhile to keep the following information in mind: Although I consider myself proficient and I’m very comfortable vectoring for approaches, I only work one sector out of seven where I get to practice these skills. There’s no way I’m going to be as good at it as an approach controller who vectors for the same approach all day long, every day. When we take over airspace from an approach control on the midnight, my comfort level goes down to somewhere near zero. In the instance where the controllers don’t work any airspace below 11,000 during the day, their comfort level is zero.

As a pilot, it would be worthwhile to keep the following information in mind: Although I consider myself proficient and I’m very comfortable vectoring for approaches, I only work one sector out of seven where I get to practice these skills. There’s no way I’m going to be as good at it as an approach controller who vectors for the same approach all day long, every day. When we take over airspace from an approach control on the midnight, my comfort level goes down to somewhere near zero. In the instance where the controllers don’t work any airspace below 11,000 during the day, their comfort level is zero.

My advice to you is to keep it simple in these situations. Be prepared to shoot the full approach with the procedure turn. In many places it is the only option. If you are offered vectors to the final, don’t push it by asking for “a tight turn near the marker.” In most cases it is illegal for a center controller to do it (equipment limitations) and in virtually all cases, it’s a bad idea. Trust me on this one. This is one situation where you don’t want to be in a rush. The idea here, the only idea, is to keep it safe. We’ll talk more about the subject later.

The Silver Lining

Before I wrap up this column, I want to point out one of the positive aspects of GPS for controllers. Everybody knows that thunderstorms turn Air Traffic Control into Air Traffic Chaos. Trying to describe the route that you wanted to recommend to a pilot was a nightmare, both on the radio (to the pilot) and in the computer (hence, to the next controller). GPS has made it a dream come true.

Before GPS, there was never a VOR where you needed it, to describe a route around a thunderstorm. With GPS there is almost always a fix (intersection, NDB, airport) right where you need it: “Cleared direct OZONE, oscar zulu oscar november echo, direct Hendersonville airport, zero, alpha, seven and then direct Greenville Downtown.”

Trust me, as clunky as that sounds, it’s light years ahead of doing it the old way. Best of all, everyone is playing on the same page. The pilot knows where he is going: No more “fly heading 270 and we’ll bend you around to the south in about eight minutes.” The controller knows where the airplane is going. Even the computer can figure it out. Well, at least until the next center border anyway.

GPS is here to stay. You know it and controllers know it. As soon as our automation catches up with GPS, controllers may even learn to love it as much as pilots. Please don’t make the mistake of thinking those automation challenges are simple to solve. They are far from it. I don’t expect you to understand them; I work with (or around) them every day and I don’t understand them. In the meantime, you might want to spend a few extra moments with the AIM and a map when you plan your flight. Who knows, if you toss in a few identifiers that the computer and the humans recognize, you might actually get to where you are going faster. If you’ll work within the system, I assure you, everyone will get to where they are going faster and safer.

Have a safe flight!

Don Brown

Facility Safety Representative

National Air Traffic Controllers Association

Atlanta ARTCC