Slim Goes To Paris

Before there could be the Lindy Hop, there had to be the Scintilla Shuffle.

My friend and fellow blogger Paul Berge revealed what a sheltered life he has led when he confessed in last week's blog to not knowing the significance of Sidney, New York. At the expense of appearing a boorish know it all—as opposed to just a boor—I can say that I most certainly did know the significance of Sidney.

Because … the Sidney Scintillas. It's easy to remember, but I got a refresher as I was reading The Flight: Charles Lindbergh's Daring and Immortal 1927 Transatlantic Crossing by Dan Hampton. I think I turned the last page just as Berge was releasing that expensively flown fly to the jaws of certain death.

Hampton's book isn't new; it was published in 2016. It showed up on my Kindle list and looked interesting. Is. Sidney merits a mention because Lindbergh's Wright J-5 Whirlwind was sustained by a pair of Sidney-made Bendix Scintilla magnetos and upon their reliability, he staked his continuance on the mortal coil.

Hampton is a retired Air Force F-16 pilot and drawing on Lindbergh's extensive notes, his book is a minute by minute account from inside the cockpit. Contemplating Lindbergh's flight from the comfort of the couch causes me to consider that, sure, Lindbergh was a shy, intense man and a steely eyed aviator, but also a bit of a wild-eyed lunatic. It may be silly to view Lindbergh's flight through the lens of modern risk assessment, but it's just as impossible not to. If you plug in the various risk factors into what we belovedly call aviation decision making, the machine would buzz and click and nothing would come out.

Let me elaborate on just two points: navigation and instrument flying. The former was in its infancy for aviators in 1927, the latter was barely a sperm cell. Indeed, after the fact, Lindbergh pioneered I Learned About Flying From That when he conceded that the next time he charged across the Atlantic, he'd damn well take a navigator. Yet, while success in the early trans-Atlantic race was elusive, cruel ironies were not. In Francois Coli, famed French World War I aviator Charles Nungesser had a superb navigator. The pair vanished without a trace attempting a westbound Paris to New York flight 10 days before Lindbergh succeeded. Slim paid his respects to Nungesser's grieving mother in Paris.

By the time he left New York, Lindbergh had been through military flight and navigation training, but he had no oceanic experience. When he departed from St. Johns for Ireland, his overwater experience consisted of the leg he'd just flown from Cape Cod. As Hampton and other authors have explained, Lindbergh was obsessively laser focused—or whatever the 1927 equivalent of that was—on endurance and hence, fuel. If he accepted that his navigation would be, to be generous, rudimentary, he could adjust by carrying a ton of fuel—literally, and then some.

Lindbergh planned a great circle route—150 miles shorter than a direct rhumb line—90 minutes of duration in the Ryan NYP. He maintained the circle with a series of 100-mile straight legs, with a compass correction at the end of each leg. The oft-discussed earth inductor compass helped with the headings, but the first time he used one of those was the morning he departed. Even Lindbergh admitted his remarkably accurate landfall at Dingle Bay was due as much to uncommonly good fortune as to heading discipline.

As Hampton reveals from Lindbergh's notes, Lindbergh had the barest notion of winds and although he had a drift meter, he didn't use it. His dead reckoning strategy required periodic position hacks, but he had no accurate estimate of how far east he was, nor of crosswind drift. He realized his landfall could have been anywhere from the Bay of Biscay to Scotland. If it had been north of that—improbable but not impossible—he'd of landed in Oslo.

The instrument flying part gives me sweaty palms. Lindbergh flew into darkness—and weather—about 12 hours into the flight. That far north and flying east, night was short, but the NYP was minimally equipped to handle heavy cloud cover, rain and icing, by any standards, much less modern ones. It encountered all three.

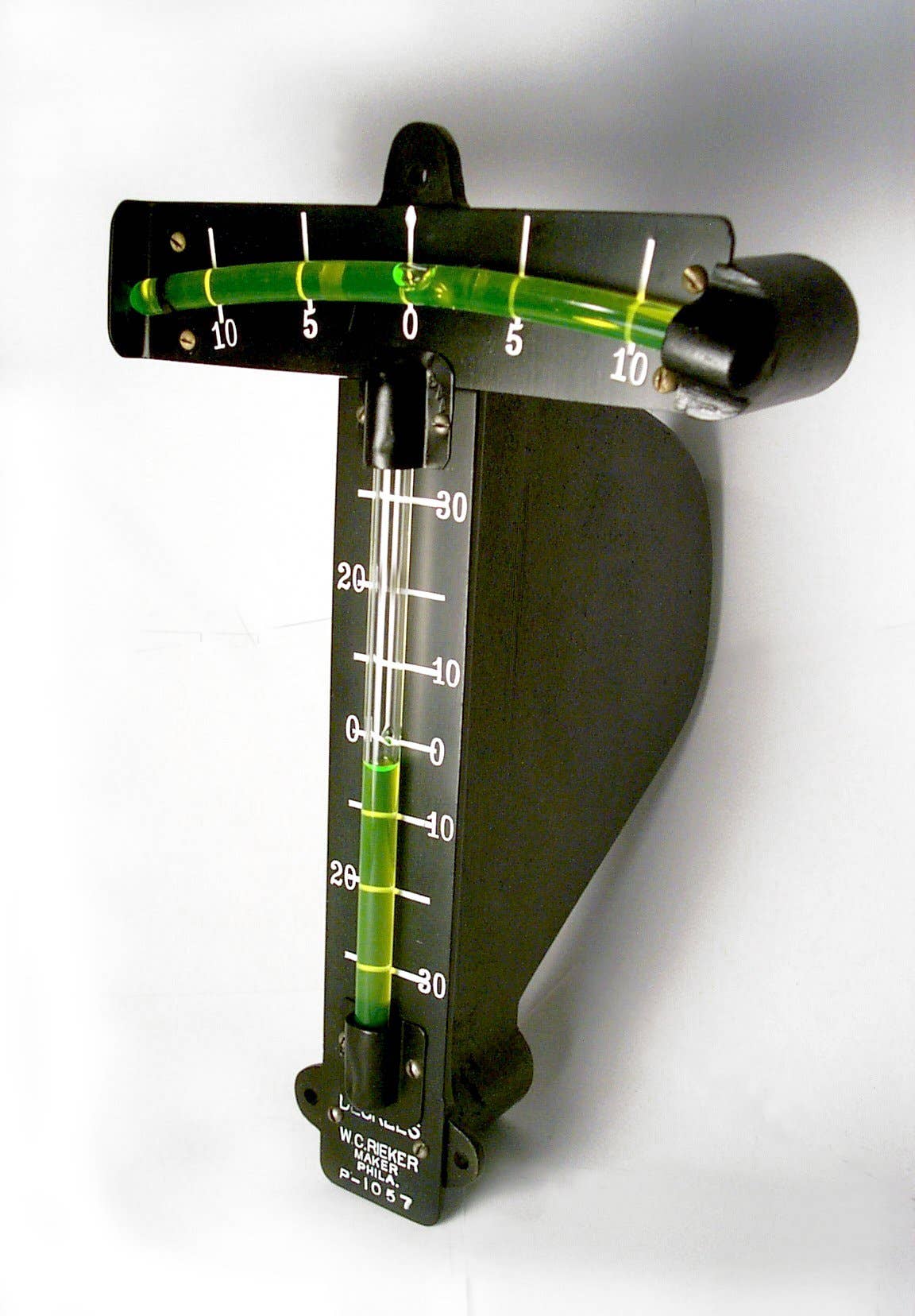

Lindbergh had a turn-and-bank indicator for roll, airspeed for pitch and a clever device called a Rieker P-1057 Degrees Inclinometer. It's a variation on the slip-skid indicator that also includes a bubble for pitch. In this photo of the NYP panel, the Rieker is the large T-shaped device in the center of the panel.

Radium being high tech in the 1920s, these instruments would have glowed enough to read them—probably. Despite a diligent search, I can't find any description of cockpit lighting in the Spirit of St. Louis, although some photos seem to show old-school shielded lamps at the top of the panel. These could have been added later. Lindbergh had at least one flashlight, but probably not the six most of us carry these days.

Either way, Lindbergh had a thousand miles of needle-ball-and-airspeed flying, much of it in utter blackness, turbulence and with no radar to pick the soft spots. At least he didn't have to worry about in-trail restrictions. As with his oceanic navigation, he was learning on the fly. Despite a couple of years in the airmail service, his instrument experience was minimal. Private pilot applicants may have as much.

Jimmy Doolittle's seminal blind flying experiments were still two years away and it took the FAA another 50 years to dream up six hours and six approaches. For Lindbergh, it wasn't so much keeping the greasy side down, but doing it hour after hour with no help from an autopilot following a sleepless 40 hours.

Lindbergh's flight put Ryan on the aeronautical map. But the company soon faded, existing today as an echo of the founder's name in Teledyne Ryan. Wright Aeronautical, maker of the J-5 Whirlwind, became Curtis Wright. It failed to make the transition to the jet age, but exists yet today as an industrial conglomerate. In little Sidney, New York, Bendix thrived, employing nearly 9000 during World War II, building mags for aircraft, tanks and PT boats.

Before the Lindy Hop was a thing, the Scintilla Shuffle was the happening dance in Sidney, according to a company history. It's what you did when you grabbed two magneto leads and gave the rotor a spin. Somehow, I think an apprentice's first day on the job in the QA department would have been just a regular barrel of monkeys. By the way, the dictionary defines scintilla as a "tiny trace or a spark." But this does not describe the output of a Bendix magneto. It is, in fact, a fat, blue knock-you-on-your-ass discharge capable igniting fuel/air mixture squeezed down by 50 atmospheres. If you've ever ruminated on this from an unintended repose on the ramp, you know what I mean. To this day, Continental Motors still makes the evolved Bendix magnetos, although the Bendix identity dissolved in a series of mergers and acquisitions. And yes, the Bendix in BendixKing has bits of Sidney DNA.

The interesting one is Rieker Inc., a little company you never heard of. Last year, the company celebrated its centenary and in an age when pilots think rudders are foot rests for the brake pedals and finding a slip/skid ball on a glass panel evokes needles and haystacks, the company still makes mechanical inclinometers. These are mostly ground bank and pitch indicators and boom angle devices for crane operators who, as YouTube videos will attest, aren't always as successful at keeping the shiny side up as Lindbergh was.

Reiker's Skip Gosnell sent me a nice photo of the P-1057 Degrees Inclinometer Lindbergh used. They no longer manufacture it, but more than 90 years later, they can still repair one if you happen to need it for that long-planned trip to Paris. There's more to it than meets the eye. In that housing behind the instrument is a triangular tube with a pinched orifice that damps the fluid flow—something you'd really appreciate if you were bouncing around in a pitch black cockpit over the Atlantic.

Reiker is in Aston, Pennsylvania, west of Philadelphia. New Garden Airport, 20 miles west, has a turf glider runway one could probably stuff a Citabria into or certainly a Cub. I feel a field trip coming on.