High-Tech Approaches: In the Future, Flight Training Will Team People with Processors

Is there a CPU in your future? If NASA’s AGATE program has its way, tomorrow’s light airplane will be nearly as computerized as a Boeing 777 or Gulfstream V is today. What’s more, the AGATE flight training workgroup is proposing a new approach to flight training with heavy emphasis on computer-based instruction and simulators. Flight Training magazine’s Greg Laslo brings you up to speed on where this is all headed.

I remember my first flight in a Level D simulator. It was abusiness jet, and I was lost among the electronic flat-panel displays, auto-throttles, andflight management systems. Totally "where-the-heck's-the-airspeed-indicator"lost.

I remember my first flight in a Level D simulator. It was abusiness jet, and I was lost among the electronic flat-panel displays, auto-throttles, andflight management systems. Totally "where-the-heck's-the-airspeed-indicator"lost.

Apparently I wasn't the first person to stare confusedly at the glass cockpit like itwas a wall of televisions at an electronics store. "That's why you fly the simulatorfirst," said the instructor pilot. "You learn how things work before you getinto the real thing. It's safer, less expensive, and it builds your confidence. That's theadvantage of technology."

Then he said, "Don't let the new gadgets confuse you — it's still an airplane.The technology is there to help you. You've got a lot more information in front of you,but pull back on the yoke, and houses still get smaller. Push forward, and houses stillget bigger."

The technology in that simulator — satellite-based navigation; simplifiedengine-management controls; computer-based systems monitoring and control; andmulti-function, flat-panel avionics displays — represents the next generation of lightairplanes.

Over the next five years, the aviation industry will attempt to woo more generalaviation pilots by putting technology to work for them. The federal government, academia,and industry have teamed to develop new programs, technologies, training techniques, andways of doing business that will dramatically change how many of us take to the skies inthe near future. The end result, they all hope, will be a safer, cheaper, more convenientpersonal air transportation system.

The key word is "personal." The system is built around the pilot, to make thejob of flying easier. Training will be easier and less expensive. A pilot certificate willbe more useful. Proficiency will be easier to maintain. "We'll be able to have safe,low-time, casual pilots," says Randy Nelson of Cessna Aircraft Company. "Mostpilots don't fly enough to stay proficient."

By tailoring new flight-training products to the pilot, especially one who can affordto fly and own an aircraft, and by designing new airplanes that permit both easy ownershipand light-aircraft transportation in nearly all weather conditions, general aviation willbe jump-started into an era of high-tech wizardry. Or so the story goes.

"I think we have to differentiate between pie-in-the-sky enthusiasm for futuretrends and realistic expectations for the near future," says NASA's Bruce Holmes."The immediate effects are easy to forecast. There will be an expanded use ofcomputing power we have available to us at low cost, and we'll design products for FBOsand flight schools that are specialized to teach people how to fly."

The impetus behind the technological infusion into general aviation is the AdvancedGeneral Aviation Transportation Experiment (AGATE), founded in 1994 by NASA and the FAA(http://agate.larc.nasa.gov). AGATE shifted into high gear last year when it announced aflight training workgroup whose goal is to develop a way to train people to fly that isless expensive and also creates better pilots. Meanwhile, other workgroups are developingnew avionics packages, power-control systems, and powerplants.

The shifting sand of flight training will be affected by other winds as well. Newaviation consumers are shaking up the way many schools do business. Quality-controlprograms initiated by manufacturers are changing the faces of flight schools themselves.And FAA plans to rebuild the airspace system will change the way we fly from one place toanother. The present way of doing things will change.

The new system is built around a "model" pilot, who will be different thanthe student pilot of the past. Last year, the general aviation industry launched GA Team2000, the industry consortium to boost the number of student pilot starts to 100,000 ayear by the year 2000. By all accounts, the first year — a test year — was successful.Student pilot starts for 1997 edged upward nearly 8 percent, to about 60,000 — no doubtpartially because of GA Team 2000. That's not a flood, but it's a reversal of a longdownward trend, and the 100,000-start goal appears to be achievable.

GA Team 2000 is targeting a pilot prospect who's affluent, adventuresome, intelligent,busy, and demanding. He — and she — has always wanted to learn to fly and is willing(and able) to pay for top-quality training, aircraft, and technology. But he'll want itserved up his way. He'll want convenient, efficient home study, inexpensive training,quicker certification, better skills, and a more useful certificate. He wants reducedworkload in the cockpit, and less overall stress to flying. And he doesn't want to pay hisdues to join the aviation fraternity. Training has to be easy and hassle free — or itwon't happen.

New Airplanes

"New aircraft will look different, feel different, and operate differently for thepilot," Cessna's Nelson says. "They'll be more user-friendly, and moreinformation will be available to the pilot. They will ease the pilot's workload, andthereby make training and proficiency easier to maintain."

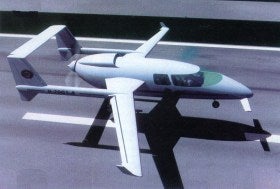

Winner of the National General Aviation Design Competition, this airplane — designed by the Kansas Consortium — should be flying later this year. |

Under those guidelines, a group of aviation pioneers in Kansas is hoping to reinventpowered flight. The engineers — graduate and undergraduate students from a collection ofuniversities in that state — will test-fly a proof-of-concept model for a turbofanpowered, single-engine aircraft designed to be quieter and more fuel efficient thancurrent piston-powered aircraft.

The students, winners of the "Design it, Build it, Fly it" category of theNational General Aviation Design Competition, an AGATE-related event, will debut theirsingle-engine aircraft at this year's Experimental Aircraft Association convention andfly-in in Oshkosh, Wisconsin.

This is the second time the Kansas Consortium — Wichita State University, Kansas StateUniversity, the University of Kansas, and Pittsburg State University — has won an awardin the four-year-old competition, which is sponsored by NASA, the EAA, FAA, AircraftOwners and Pilots Association, the Air Force Research Laboratory, and the Virginia SpaceGrant Consortium. The Kansas colleges won a $10,000 seed grant to build the design. Theconsortium's 1996 entry was a composite, diesel-powered single-engine kitbuilt design thatwould have the performance characteristics of a new Cessna Model 172 — at about half theprice.

That's the point of the competition — to use the academic world's aeronautical brainpower and resources to create an aircraft that appeals to recreational and businesspilots. The competition is open to undergraduate and graduate students enrolled atfour-year engineering schools. They must design a fixed-wing, single-engine, single-pilot,propeller-driven aircraft for two to six occupants that cruises at 150 to 300 knots for800 to 1000 nautical miles.

Their designs use state-of-the-art technology, including VHF datalink (VDL) radios,which reduce the amount of spoken communication between ATC and the pilot. VDLs receivecoded radio signals about weather, clearances, traffic, and other advisory information.Satellite navigation systems will include terrain and obstacle avoidance.

Aircraft of the future could employ impact-absorbing composite construction, havesingle-level power controls, and use alternative powerplants, including diesel andturbofan engines. Both powerplants are being developed now through the General AviationPropulsion (GAP) program at NASA's Lewis Research Center. By importing existing technologyto aviation from other industries, the competition sponsors hope to reduce productioncosts from 25 to 40 percent.

The technology isn't that far away.

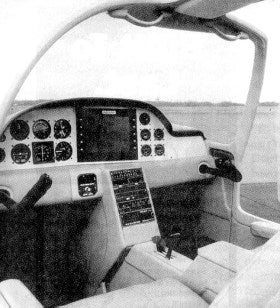

In the AGATE airplane of the future, the instrument panel will be home to several multi-function flat panel displays. Part of the future is here today in the Cirrus SR20, which has a flat-panel screen that displays engine and navigation information. |

In cold, snowy Duluth, Minnesota, engineers from Cirrus Design are completingcertification work on the Cirrus SR20, a four-place, all-composite, 160-knot,single-engine aircraft. This year the company expects to receive the type certificate forthe airplane that "gives pilots long-awaited access to today's technologicaladvances."

"In concept, the goals we strive for with the SR20 is what AGATE is strivingfor," says Cirrus' Dean Vogel. "It will be easier to fly and to maintaincurrency in nearly all weather conditions."

The SR20 is not your father's single-engine airplane. It's a sleek, fast, long-rangecruiser. But that's on the outside.

On the inside, it incorporates cockpit design features currently found only on someexperimental designs or in large, state-of-the-art commercial aircraft. The pilot operatesan ergonomically designed side stick — gone is the traditional W-shaped yoke jutting fromthe panel. The pilot controls engine power with a single lever and monitors navigation andengine instruments on a multi-function, cathode-ray tube in the center of the instrumentpanel.

On the drawing table, the company designed the SR20 to be crash-survivable. Theproduction model will use seats that absorb high impact forces and a Ballistic RecoverySystem parachute to safely lower the airplane, should it become disabled or should thepilot lose control such as in inadvertent VFR flight into IFR conditions.

It's a contemporary sedan with wings, and according to Vogel, that's what future pilotswant — and need.

While more than half of all pilots fly for the challenge (57.5 percent, according to anew Flight Training survey), far more (more than 70 percent) fly for recreation andenjoyment. For the recreational, weekend pilot, today's aircraft may require more time andeffort to maintain currency and confidence than they have to give. Those pilots eventuallylose interest. Or worse.

"The only way to make aviation less expensive is to get more people to doit," Vogel says. "To do that, you have to take away some of the challenge. Forsome, it may be too much of a challenge. Look at it this way — some people like to domath problems in their head. Fewer people like to do math problems in their head whenthey're stressed. Even fewer people like to do math problems in their head when they'restressed — and they're flying in instrument conditions with the mother of their childrensitting next to them. A lot of people like to fly, but when they aren't current, itbecomes stressful. So, they don't fly as much, and they don't use their airplane as muchas they once did."

To break this cycle, an airplane must be easier to use.

"The AGATE ideals will be to general aviation what the graphical user interfacewas to the computer market," Vogel says. "People bought computers beforeMicrosoft Windows came out, but they were mostly technically oriented people — likepilots are today. Windows, because it was easy to use, really made the computer ahousehold appliance."

New Classes

If the pilots and airplanes are changing, so must the method of teaching.

Currently, only about half the pilots who begin flying lessons actually earn theirrecreational or private pilot certificate. Also, an untold number of certificated pilots,having neither the confidence nor the reason to fly, lapse into inactivity when theirmedical certificate expires.

The general aviation industry — certainly the single-engine, recreational part of it— needs all the active bodies it can get, lest the private pilot become an endangeredspecies.

AOPA warns that fewer pilots mean less representation before — and protection from —local and national governments. Less representation means fewer airports, as cities andneighborhoods petition to close the local, non-towered, general aviation airport. Fewerairports mean fewer opportunities for pilots — and less margin for safety. And so itgoes.

Pilots quit flying for a variety of reasons. They may not have the time, the money, orthe energy to fly. In any case, general aviation isn't fulfilling their needs. Byrebuilding the training curriculum so earning a pilot certificate is easier and cheaper,AGATE flight training would attract and keep student pilot prospects that previously wouldhave been scared away.

The AGATE flight training workgroup — Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University, Ohio StateUniversity, Florida Institute of Technology, Advanced Creations, Cessna, and Jeppesen —is drafting a curriculum that would unify training. The concept is to have student pilotsearn a combined private pilot certificate and instrument rating.

The workgroup's first task is completing a one-step training curriculum that will takea new student through the instrument rating. The combined course will be shorter than thepresent separate training programs, and it should cost about 25 percent less. Next, theworkgroup will draft single-lever power control and multi-function, glass-cockpit displaytraining modules, both to be completed by 2000. Then the team will write free-flight andicing modules. The FAA is now developing free-flight, which essentially dismantles thecurrent airway system and permits flexible routing and cruising altitudes.

The workgroup will have a variety of tools available to it. Computer-based instruction(CBI), Personal Computer-based Aviation Training Devices (PCATDs), free-standing FlightTraining Devices (FTDs), and new airplanes with new systems will all be instrumental inthose training programs. The magic mix is still under development.

"The AGATE emphasis is on cost, not on time, " says Steve Hampton of ERAU."Time in an airplane is expensive. Time in a PCATD is very inexpensive. Five hours ina PCATD versus one hour in an airplane is cost-effective."

CD-ROM ground school courses will bring the best of all worlds to student pilots —video-, textbook-, and classroom-based study guides. Portable and convenient, thecomputer-based learning programs allow students to study at their leisure. "We'lltake advantage of multimedia for training that can be driven by the student," Nelsonsays.

At EAA Oshkosh 97, both Cessna and Jeppesen introduced computer-based instructionalprograms. "CBI brings flight training to people in a very comfortable way that's notbeen available before," says Cessna's Jan McIntire. "CBI gives studentsconvenience and flexibility. It makes flight training that much more accessible. A pilotcan carry a notebook computer with a CD-ROM drive instead of stacks of books, and he canstudy on an airliner or in a hotel room. It'll also teach younger people in a way they arefamiliar and comfortable with. It's entertaining, it incorporates the best educationaltechniques, and it doesn't allow students to continue until they've mastered eachlesson."

Cessna's CBI private pilot course will be available this spring through Cessna PilotCenters. Jeppesen's CD-ROM is already part of their student pilot kit.

CBI will allow certificated pilots to participate in recurrent training also. Safetyseminars and continuing education courses could be written for CD-ROM. Home study wouldactually result in proficiency that meant something, Nelson says.

CBI, though, is not general aviation's magic bullet. It's a popular training method —and other industries have put it to use with encouraging results — but CBI offers noguarantee that it will work for general aviation. SimuFlite, the corporate pilot trainingcompany in Dallas, tried to use CBI in its programs, but it failed and the company stoppedusing it, Hampton says.

"Developing CBI is expensive and time consuming," Hampton says. "To makeit educationally sound isn't an easy task. It has to be attractive to hold your attentionfor 20 or 30 hours, and there has to be interaction. But even then, some students won'tlike CBI. We still have to design curricula for all learning styles."

Reliance on computers for training — CBI, PCATDs, and high-tech cockpits — may makeaviation seem too much like a game, critics say. "People understand that and areworking hard to make that clear," Cessna's Nelson says. "You don't get a GameOver' message in the real world. You have to make the entire program a little more robustthan a video game."

That obstacle, and others, has to be overcome. "We have to be sure we don't talkdown to professionals," Hampton says. "With doctors, lawyers, and other highlyeducated individuals taking flight training — the market GA Team 2000 has targeted —instructors and educational systems have to treat them like competent, intelligentadults."

But attention to customers isn't solely a technological problem.

New Schools

Diamond Aircraft Industries opened the doors of its first Diamond Flight Center inOntario, Canada, on December 1, 1997. The manufacturer owns the school but a contractorwill provide flight training services to customers. Diamond spent more than $750,000 tobuild the 12,500-square-foot facility, which includes a flight school, up-scalerestaurant, and bar.

Diamond's school will be a test center for Diamond curricula, marketing efforts, andcustomer-service efforts. The main reason for the program, Diamond says, is to offer itsKatana DA20 operators a wealth of business knowledge to help them run a more profitableoperation. "The goal was to test and implement different procedures — how we market,new ways to implement our flight training device, new programs, new procedures, and newsyllabi," says Diamond's Jeff Owen. "It'll allow us to test different things tostudy our market — to see what makes them come and what makes them come back."

A week after the Diamond school opened, a group of flight school managers converged onIndependence, Kansas, to attend the first-ever, new-and-improved Cessna Pilot Centerrefresher seminar. Cessna restructured its Cessna Pilot Center training program toemphasize customer service, marketing, sales, and solid business practices among itsmember flight schools. Those schools that don't measure up will be cut from the program.

"Everybody knows what the fundamentals of business are — marketing and customerservice — but it's how you apply those fundamentals," Owen says. "The reallygood schools out there aren't doing anything everyone else couldn't do. The secret isdoing people-oriented things."

The flight school of the future will probably resemble a corporate office park or amodern, high-end fixed-based operator rather than a contemporary flight school, with itstraditional "rumpus-room" decor. Neon and windows will replace wood paneling andposters.

It will be a different marketplace out there.

It will have to be. Otherwise, potential flight training customers will continue tospend their money elsewhere — on personal watercraft, golf, or other leisure activities.If that happens, AGATE, GA Team 2000, GAP, and every other industry-revitalization programwill have lost the race before they leave the blocks.

The training industry has acknowledged this fact. Cessna will disassociate with CPCsthat don't comply with contracts and will sign up rising-star flight schools. Diamond willtrain its DFC managers in flight school operations. GA Team 2000's InfrastructureCommittee will examine how to rebuild the base of flight schools. The National AirTransportation Association offers its second season of Flight School Managers seminarsthis year. Flight Training's four-year-old sister publication Flight School Businessoffers how-to, back-to-basics information on flight school management. Between industryinput and consumer demands, the next few years will bring big changes to flight schools.

New Systems

Aviation historians will look back on GPS satellite navigation as a turning point ingeneral aviation. Manufacturers have sold more than 150,000 aviation units. That's a dropin the bucket compared to the more than three million purchased for other purposes, butthe FAA expects to make GPS the sole means of navigation within the next 15 years.

A GPS-only airspace system will change how we fly, when we fly, and how we get there.

Already, AGATE members are drafting curricula that will teach pilots to fly in thecoming free-flight, nearly all-weather National Airspace System. Already AOPA is pushingfor the FAA to design more GPS-only instrument approaches — the majority of today's GPSapproaches are overlays of existing non-precision instrument approaches. That's only ashort-term solution, the association says, and GPS-only approaches will be vital to earlyphases of Wide Area Augmentation System (WAAS) implementation, which will provide a GPSsignal accurate enough for precision instrument approaches.

The FAA expects to have a full WAAS network up and running by 2002, in spite of earlyorganizational and contractual problems. The FAA plans to phase out ground-based navaids,such as VORs and non-directional beacons (NDBs), in 2005 (with a few exceptions, such as afew on-airport navaids at selected locations, which will be phased out completely by2010).

In a "virtual highway in the sky," pilots will use sophisticated situationindicators in one package that provide the same three-dimensional information as ahorizontal situation indicator (HSI) and attitude indicator together do, NASA's Holmessays. Just follow the bouncing white ball.

A free-flight system will require different avionics — multi-function displays, suchas the one in the SR20, that display communication, navigation, and satellite (CNS)information; VDL datalink radios; and new aircraft situation indicators.

The result will be Category I instrument approaches — 200-foot ceiling andone-half-mile visibility minimums — around the United States, which translates into nearall-weather flying for most instrument-rated pilots. The system will give themthree-dimensional guidance on precision approaches at more than 5,000 public-use airportsnow served only by non-precision instrument approach procedures with higher minimums.

That's important to safety.

In studies of big-airplane accidents, most controlled flight into terrain (CFIT)accidents occur when the pilots deviate vertically from the glideslope, not laterally,says the Flight Safety Foundation. Furthermore, big airlines are five-times more likely tocrash on non-precision approaches than on precision approaches, FSF says.

FAA critics and Congress question whether the FAA can implement a free-flight WAASsystem in the time frame the agency has set. The FAA says it can, and points to the 1996Atlanta Olympics. There VHF datalink radios gave graphic weather information, trafficinformation, flight planning and clearances, and textual automatic terminal informationservice (ATIS) and Notice to Airmen (NOTAM) information to 92 aircraft using Olympicairspace. They also point to a GPS-based approach at Minneapolis International Airportthat allows airline pilots to fly an ILS-like precision approach.

New Questions

AGATE's new technology means nothing if it doesn't make flying safer.

Airlines and corporate operators fly jet aircraft with glass cockpits and sophisticatedavionics that reduce the complexity of flying big, expensive aircraft. The results — inspite of best intentions to use technology to make flying easier and safer — aren'tencouraging.

"With more than 4,000 hours in advanced cockpits, I've found that these supposedlyfail safe' systems can occasionally set us up — and then let us down in a bigway," wrote one pilot to NASA's Aviation Safety Reporting System.

"We missed the crossing altitude by 1,000 feet," another pilot wrote to ASRS."The captain was busy trying to program the flight management computer. Being new inan automated cockpit, I find that pilots are spending too much time playing with thecomputer at critical times, rather than flying the aircraft. No one looks outside fortraffic."

And another pilot wrote — "We descended 400 feet below the 10,000-foot crossingaltitude. How did this happen? I suppose the wizardry of the glass cockpit and twonewcomers who were not aggressive enough intervening when the computer did other than whatwas expected."

So if high-time airline pilots have difficulties with new, high-tech, glass-cockpitaircraft, what will the new general aviation pilot experience? What about the AmericanAirlines crash in Cali, Colombia, in which the pilots flew off course and selected anincorrect waypoint on their flight management computer?

"An AGATE airplane will be more sophisticated in terms of displays," Hamptonsays. "It won't have an auto-throttle like a big jet, but it will have a simplifiedpower-management system. The pilot still has to understand how the systems operate, butthat's a cognitive function — it's a management function. You'll need basic skills to beable to manage the system."

That function is what the AGATE curriculum team has to train pilots to perform. "Ithink we can do things a lot simpler than we do it now," Hampton says. "But wehave to build a solid foundation of airmanship skills. Technology is changing, and we haveto be careful to not let the technology get out of control. AGATE allows us to takeadvantage of those changes and see what is good and what is bad. It's better that ithappen this way than for the FAA to tell us we have to change."

Each new system will require new training, and an AGATE aircraft and a Piper J-3 Cubwill share only distant general aviation lineage — just like a Gulfstream V and Beech 18."But we're trying not to make two classes of pilots — AGATE and non-AGATE,"Hampton says.

Each new system will require new training, and an AGATE aircraft and a Piper J-3 Cubwill share only distant general aviation lineage — just like a Gulfstream V and Beech 18."But we're trying not to make two classes of pilots — AGATE and non-AGATE,"Hampton says.

In reality, though, the pilot-aircraft interfaces will be very different, and the classdivision may happen.

Which is unfortunate, because I also remember the first time I flew an open-cockpitbiplane — a big, beautiful, blue and yellow beast with only a handful of steam-gaugeinstruments. In a steep bank, I looked over the side of the open cockpit to see nothingbut 3,000 feet of air below me and wings all around me. It was magical. It wasexhilarating. It was pure, unadulterated flying, high above the cross-hatched fields ofMidwestern farms, and it was the first time I felt like a pilot.