Great Plains Weather

For some, flying is just braving the traffic pattern or short, local flights. But serious long-distance flying or commercial operations will eventually bring you to the heart of the Great…

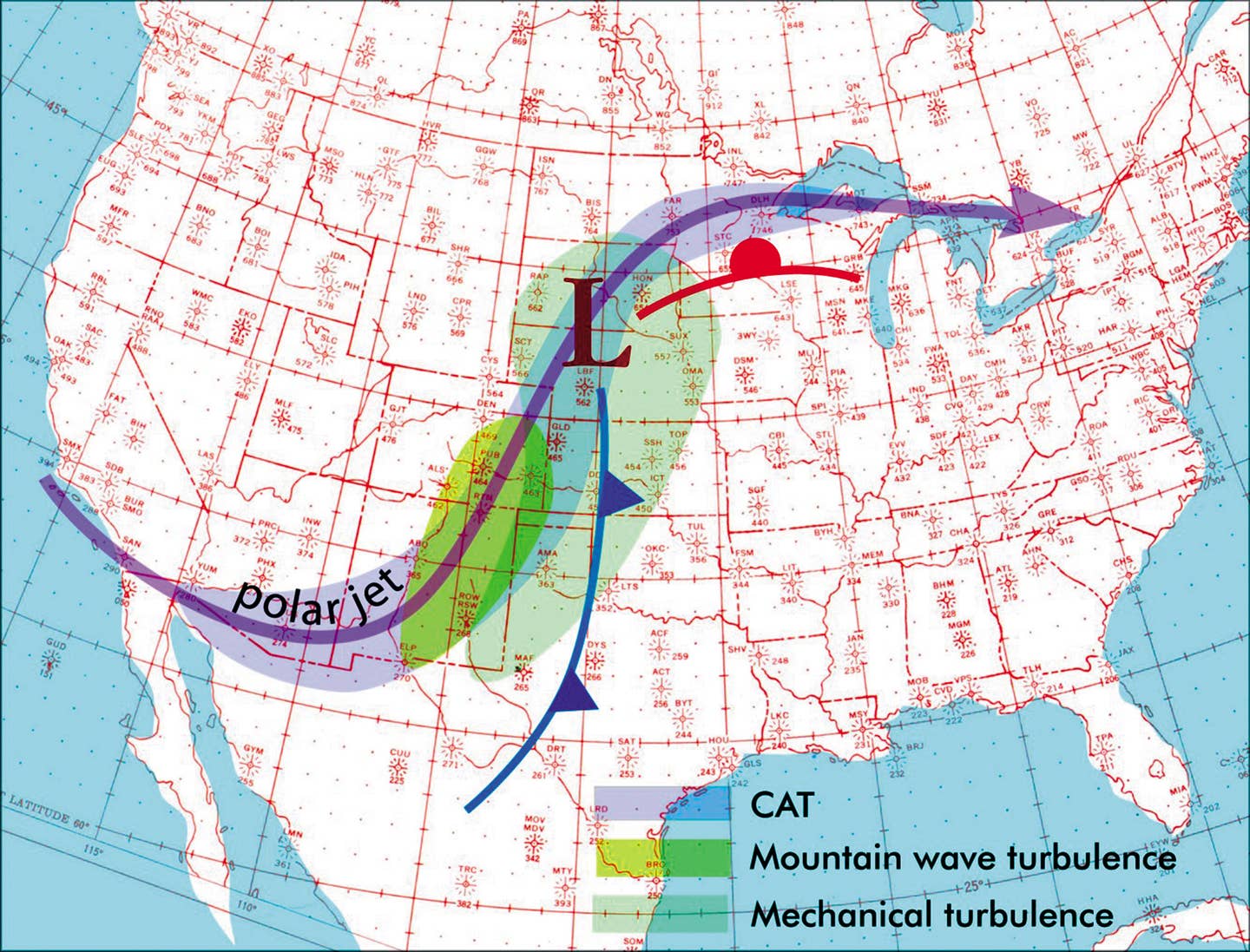

A typical Great Plains weather system can bring significant turbulence.

For some, flying is just braving the traffic pattern or short, local flights. But serious long-distance flying or commercial operations will eventually bring you to the heart of the Great Plains. Meteorology captivated me because of the incredibly turbulent and strange weather in this area. I chased tornadoes for 15 years and forecasted weather for B-1B training routes in remote parts of Texas, Oklahoma, and Colorado. So sit back and enjoy: Here’s an insider’s perspective on aviation weather in this unique part of the world.

The verdant farmfields of the Platte began to disappear and in their stead, so far you couldn’t see to the end, appeared long flat wastelands of sand and sagebrush. I was astounded.

“What in the hell is this?” I cried out to Slim.

“This is the beginning of the rangelands, boy. Hand me another drink.”

We passed the bottle. The great blazing stars came out, the far-receding sand hills got dim. I felt like an arrow that could shoot out all the way.

—On The Road, Jack Kerouac

The Big Picture

The Great Plains is the vast flat region that extends from the Rocky Mountains to the Mississippi River, covering most of the Central Time zone. It extends as far south as south Texas and north to Alberta and Saskatchewan. Geographers insist the Great Plains lies west of Dallas and west of Kansas City, but forecasters extend the region east to Des Moines, St. Louis, Little Rock, and Shreveport as the weather behaves much the same there.

Most of the Great Plains was laid down by erosion and weathering of the Rocky Mountains, providing a flat surface that gradually decreases elevation from over 5000 feet near Denver to 500 feet near St. Louis. As humans settled the area it became the home of the Sioux, the Pawnee, and the Comanche tribes, who followed the great buffalo migrations and prospered. With the European settlers in the 1800s, the Great Plains became a vast agricultural region connected by railroads and barges.

The region became known for its turbulent weather. The diaries of settlers in the 1860s and 1870s spoke of vast whirlwinds, large hail, and incredible lightning displays. By the 1890s, when photography was flourishing, tornado pictures were widely circulated and captivated the imagination of the country. This led to the Wizard of Oz becoming the icon of Great Plains weather (Trivia factoid: the world’s tornado hotspot is not Kansas, but is actually about halfway between Amarillo and Oklahoma City).

Great Plains Playbook

To understand the meteorology, you have to know a bit about the geography and the atmospheric patterns found there. In meteorology, you are the product of your environment, and by going around the compass, we see all of the influences that contribute to our weather. This technique is actually quite valuable for quickly putting weather at your destination into context as you review planning charts and read TAFs.

To the north we have the vast Canadian arctic—essentially an extension of the Plains. It’s flat and mostly continental, albeit full of bogs and muskeg in the summer. In the winter, though, it’s covered by a semi-permanent snowfield, insulating the air mass from the warm Earth, and turning Canada into a powerful winter cold air factory.

To the southeast is the Gulf of Mexico. With water temperatures averaging 65 degrees F in winter and 80 in summer, evaporation in the Gulf is a powerful process. It’s the single biggest contributor to atmospheric water vapor east of the Rockies, and it shapes the climate there year-round. Whenever winds are blowing from the Gulf, they’re likely to transport humidity and clouds.

The north-south Rocky Mountains to the west act as a channel, increasing the importance of anything located to the north or to the south. But some Pacific systems migrate west to east. In crossing the Sierra Nevadas and Rockies these systems are usually dry when they reach the lee slopes of Colorado and New Mexico, but often link with Gulf moisture to regain their original strength.

Although not often stressed in weather books, the southwest regions are important too. These are the deserts and plateaus of far-west Texas, Mexico, New Mexico, Arizona, and the Four Corners region. These areas tend to be warm and dry, favoring hot downslope winds, drought weather, and fire-danger conditions. In spring, the leading edge of this air forms the dryline.

In the east—the Appalachian region, the Midwest, and the southeast forests—air masses here are usually stagnant and hazy. This air doesn’t often make it west to the Plains, but when it does, it brings mild weather and hazy conditions.

Winter Patterns

One of the biggest factors shaping United States winter weather is the strengthened upper-level flow during the cold season as the jet stream relocates further south. The LAX-JFK route, normally just five hours, can shorten by 90 minutes thanks to the strong tailwinds. This flow perpendicular to the Rockies often creates mountain waves and moderate to severe clear air turbulence in the High Plains.

But this perpendicular flow also develops lee-side troughing with low pressure. It often extends from western Alberta down to southeast Colorado and frequently is found on weather maps. As a result, the normal wind flow on the Great Plains is often from the southeast, flowing northwest into the trough.

The other winter pattern we see in the United States is the regular march of cold Canadian high pressure systems southeastward. When you see one of these huge high pressure areas, it helps to think of them as a big blob of cool air. Sometimes these blobs are “trapped” in Canada by low pressure in the Plains or strengthened troughing out west.

But other times you’ll see a large blob pushing its way into the United States, preceded by an east-west cold front, and we say the Canadian polar air is dominant, sometimes called a “prevailing high.” Most of the time, the center of these Canadian air masses tracks toward the northeast U.S., but they can occasionally track more directly south toward Texas, Arkansas, or Louisiana.

As these Canadian air masses reach the Great Plains, surface winds become northerly. This northerly layer gradually deepens, from only a few thousand feet in shallow cold outbreaks all the way to the entire troposphere in particularly strong outbreaks. Since the air mass consists of very cold air flowing over warm terrain, it’s warmed from below creating a cold-overwarm profile near the ground. Behind fresh cold fronts, expect shallow instability, gusty surface winds, and lots of mechanical turbulence in the lowest few thousand feet. Climbing will get you a smoother ride.

While these patterns are underway, the lee side troughing on the High Plains often remains. It might be covered temporarily as the cold air mass arrives and passes, but winds quickly revert to southeast or south. If a cold high departs to the east, the lee side trough temporarily taps this air mass and conditions will be cool and dry. But with weak Canadian highs, the lee side trough is more likely to tap moist Gulf air, bringing clouds and unsettled weather north.

Spring Patterns

In spring, the snowfields disappear in Canada, and the cold air factory begins shutting down. Cold outbreaks still arrive in the eastern states, but are much weaker. This means that lee side troughing patterns are much more likely to tap air from the Gulf of Mexico. When this happens, warm conditions and moisture can advance far into the Great Plains.

Early in the spring, nocturnal radiation is strong and there are often cool air masses in place over the Great Plains. As soon as deep southerly flow becomes established in the lower levels, it often overrides these cool air masses at the surface, producing an effect called isentropic lift. In short, the southerly flow tends to rise as it flows over these cooler air masses, and since it’s already carrying abundant moisture from the Gulf, clouds and poor weather are likely.

This gives us another rule of thumb: When there’s cool weather on the Great Plains and deep southerly flow develops, we should expect stratus and fog. This effect is particularly pronounced in Texas and Louisiana between November and May, where there’s a sharp transition from warm muggy air to cool air inland. This can produce extensive broken to overcast layers from the surface to 4000 feet, particularly in the morning hours. Austin, Dallas, Shreveport, and Houston are affected the most.

Furthermore, the weather disturbances from the west and the interaction with Gulf moisture create an enhanced risk of thunderstorms and severe weather. The two key ingredients are high dewpoints in the low levels and cold temperatures aloft, which are found within nearly all upper-level troughs. Once these come together, the instability brings cumulonimbus clouds. A boundary helps focus the release of this energy, which is why fronts, troughs, outflow boundaries, and drylines are the best places to look for severe weather.

And for supercells and tornadoes, the key ingredient is strong turning of the wind in the lowest one or two thousand feet of the atmosphere. This is most likely to happen on the east side of well-developed surface lows. Coincidentally this is where we usually find warm fronts, giving our next rule of thumb: Severe weather is more likely to occur along warm fronts. Other favored areas are anywhere east of “mesolows,” which are like small ripples in the surface wind field. We won’t teach you how to forecast these, but we will urge you to use the convective weather products at Storm Prediction Center, www.spc.noaa.gov. I can assure you that some of the sharpest minds in severe weather forecasting work there, and their convective outlook and mesoscale discussions will accurately tell you how things will unfold.

The most violent thunderstorms are found in Texas in April, shifting north to Oklahoma and Kansas in May, then to Nebraska in June, and the Dakotas by July. As the peak of severe weather passes on its way north, the weather at that location transitions almost immediately to summer-like conditions and lots of VFR weather. This is due to the migration of the jet stream northward and warming of the upper troposphere. Remember from the Aviation Weather circular that any trend toward “warm-over-cold” means increasing stability.

Summer Patterns

On the Great Plains, summer tends to immediately follow the peak in thunderstorm activity. Summer patterns are characterized by southerly flow, broken to overcast patchy fog and stratus in the morning, and lots of SCT040 by afternoon.

Weak Canadian fronts and backdoor fronts from the eastern United States are the main weather makers and often become quasi-stationary for many days of rain showers or thunderstorm activity, especially in Iowa, Missouri, Arkansas, and adjoining parts of Texas, Oklahoma, Kansas, and Nebraska. Summer flash flood situations are usually associated with these patterns.

Also, large thunderstorm complexes can reinforce or even replace these fronts, adding to the weather misery and extending the bad weather into successive weeks. That leads us to another rule of thumb: If it’s summer and there are thunderstorm complexes with a weak wind profile, expect the pattern to last multiple days.

The hottest weather of summer comes when large upper-level highs (“subtropical highs”) cover the area. Global models are very good at forecasting these out to 240 hours, and when you see them covering your part of the Plains instead of their usual haunts (Mexico and the Gulf), it is a strong indicator you’ll be seeing hot weather and high density altitudes.

By late July or early August, the subtropical high often shifts northward into Colorado, Kansas, or the Tennessee-Kentucky area. Not only does it place those areas under hot stagnant weather, but it puts the Gulf Coast and Southern Plains under easterly tropospheric flow. Believe it or not, it’s common to have a tailwind in August when flying west.

This regime is called “easterly flow” and the patterns tend to have strong tropical characteristics. Easterly waves can even ripple through this pattern, bringing an increase in thunderstorm activity every two or three days, especially in Texas. The moisture is also very deep, with extensive scattered to broken layers at all altitudes, and hazy conditions can reach well up into the jet altitudes. This easterly flow characterizes much of late summer.

Fall Patterns

Autumn in the Great Plains tends to be stagnant, with weak lee side troughing in place that couples with the large heat low covering the southern Rockies. Midwestern cold fronts become a little stronger and every one or two weeks they bring an increase in rain as they stall out over Texas, Oklahoma, or Kansas.

Starting in early September and particularly in October, the Great Plains can be affected by landfalling hurricanes. These storms originate mostly from the Gulf, but can also cross the Sierra Madres from Baja California. They can reach as far north as Oklahoma and Kansas. The wind fields usually die out during the first day the storms come inland, but the moisture fields can be tremendous and have a huge impact on the Great Plains. When the remains of these hurricanes come inland, it’s a good idea to plan on lots of afternoon thunderstorm activity along their path, with MVFR and patchy IFR, more than you’d normally expect.

As fall continues, snowfields become established once again in Canada and we see the return of the strong Canadian high pressure systems, that push southward into the Great Plains. The pattern returns to winter once again and the cycles continue.

Tim Vasquez has done most of his 30 years of forecasting on the Great Plains, and continues to program, write weather books, and process weather data from his home office in Texas.

For more great content like this, subscribe to IFR!