Thanks for the Landing

All pilots vividly remember their primary flight instructor, but most of us lose touch with our original mentors as we pursue our aviation careers. AVweb reader John Laming is a striking exception. This former Royal Australian Air Force fighter and bomber pilot and retired 737 captain writes a poignant account of the day a few years ago when he had the chance to offer his old military flight instructor – age 80 and nearly blind – the left seat of a Piper Cherokee, and talked him through his final landing. Dont miss this touching story.

Lockheed Hudson |

In my career I have flown with many flying instructors, and likemost pilots, I remember my first flight quite vividly. It was in a Lockheed Hudson flownby Captain Harry Purvis AFC, and which took place at Camden near Sydney in 1949. Harry wasa highly-experienced and well-known pilot who had flown with Charles Kingsford Smith inthe Southern Cross. I sat on the metal floor of the Hudson and suffered the pain ofblocked ears because no one had told me how to relieve the internal pressure.

In my career I have flown with many flying instructors, and likemost pilots, I remember my first flight quite vividly. It was in a Lockheed Hudson flownby Captain Harry Purvis AFC, and which took place at Camden near Sydney in 1949. Harry wasa highly-experienced and well-known pilot who had flown with Charles Kingsford Smith inthe Southern Cross. I sat on the metal floor of the Hudson and suffered the pain ofblocked ears because no one had told me how to relieve the internal pressure.

It was two years later before I saved enough money to take my first dual trip in aTiger Moth. The instructor had a thick European accent that was exacerbated by hisbellowing unintelligible orders down the Gosport tube. The flight was a disaster, and Ididn’t learn a thing.

Determined to learn to fly, I saved more money and had another go. This time theinstructor was a kindly man called Bill Burns. Bill was a wartime pilot who had flown inNew Guinea and now worked for Qantas as their flight safety manager. He sent me solo aftereight hours of excellent instruction.

How I Met Sid

Shortly after, I joined the RAAF to be a pilot, and it was during my early trainingthat I first met Flight Lieutenant Sidney Gooding DFC. He had been a Lancaster pilot inWorld War II, and after the surrender of Japan in 1945, had stayed in the RAAF, and wasposted to Japan as part of the Allied Occupation forces. There he flew Mustangs and anoccasional Spitfire. Later he flew Lincoln bombers against the communist terrorists inMalaya, after which he returned to Australia to become a QFI (qualified flyinginstructor).

The Korean war began to hot up in 1951. As pilot recruiting increased, Sid, along withother experienced former wartime pilots, were posted to the instructional staff at RAAFBase Uranquinty near Wagga, in New South Wales. Uranquinty had been turned into a migrantreception area in the early post war years, and when in 1952 the decision was made toreturn the aerodrome to full Air Force control, it became No 1 BFTS (Basic Flying TrainingSchool.)

Douglas C-47 Dakota |

At the time, I was one of 45 trainee pilots on No 8 Post War Pilot's Course and afterinitial training at Point Cook and Archerfield we were sent to Uranquinty in April 1952 tostart basic training on Tiger Moths and Wirraways. There, my instructor was FlightSergeant Vernon Jackson who had previously flown Dakotas. Vern was a real gentleman and afine instructor who eventually retired as a Group Captain. Fifty years later, we stillkeep in touch. There was a wealth of experience among these pilots with most having flownoperational tours on Beaufighters, Bostons, and Mosquitos. Others had flown Liberators,Hudsons and Spitfires. Apart from the inevitable bad-tempered instructor that isencountered sooner or later at all flying training establishments (including theairlines), we were fortunate to encounter keen and dedicated men who actually enjoyedinstructing.

Sid's Groundschool

|

Besides flying, Sid Gooding gave class lectures on airmanship. Our first impression wasof a genial smiling man with a battered pipe and a wry sense of humour. On his uniform wasthe purple and white striped ribbon of the Distinguished Flying Cross. We all wondered howhe had won this decoration for bravery, but in those days it was not the done thing toask. His officer's cap was set at a rakish angle and he looked entirely at ease.Conforming to RAAF discipline and good manners, the class stood up as he entered the room.He would thank us for the gesture and tell us to be seated.

After introducing himself, Sid unfolded a large blueprint and pinned it to theblackboard. With a grave expression he then explained that he enjoyed inventing things,and that the blueprint was of a pair of steam-driven roller skates, with a tiny fireboxbuilt into the heels and the wheels driven by pistons rather like a steam locomotive. To astunned classroom of trainee pilots, he proceeded to go into the details of its design.This was far better than the dry formula of aerodynamics or the study of saturatedadiabatic lapse rates, and Sid soon got our attention. Five minutes later, he put away hisblueprint and talked about the real subject of his lecture, which was carburetor icing onTiger Moths and Wirraways.

Each lecture would be preceded by the blueprint of yet another invention before gettingon to more serious matters such as cockpit drills, propeller swinging, thunderstormpenetration, engine handling and aircraft captaincy. One strange invention that Sidproduced was a Phillips electric shaver head, manually operated via a flexible wire cable.The blueprint showed one end of the cable connected to the shaver, while the other end wasattached to a large rubber suction cup. Sid explained that while flying the Lincolnbomber, an inboard engine would be closed down and the propeller feathered. As theaircraft slowed down, the cable would be cast out of a window and an attempt made tolassoo the sucker to the spinner of the stopped engine. If this was successful, the enginewas restarted and the rotation of the spinner would allow the cable to turn the blades ofthe shaver, and on long flights the crew could all have a shave. We never quite knew ifSid was serious or having us on! But I do know that no one ever went to sleep in Sid'slectures, for fear of missing the good gen on airmanship or his inventions.

Flight Training

Each instructor was allotted four students, and those that had drawn Sid were indeedfortunate, as he proved to be kind and patient with even the most backward students. Inthe back of our minds was the constant worry of being scrubbed from flying because ofperceived lack of ability. Those unfortunates who failed flying tests were posted away toundergo a navigator's course at East Sale, while others were discharged from the RAAFaltogether and sent to back civilian life. I was nineteen years old, and with no home andno job to return to, the prospect of being scrubbed was terrifying and made me work allthe harder.

But with a good instructor in the back seat and the willingness to burn the midnightoil, the chances of not making the grade were greatly reduced. Sid's students were usuallysuccessful, while Vern Jackson's expert tuition set the framework for my eventualgraduation as a pilot. This was despite my next instructor at the Advanced Flying TrainingSchool at Point Cook who was a real screamer. However, fortune smiled upon me, and Ireceived my wings in December 1952.

A Memorable Cross-Country

B-24 Liberator |

On one occasion I flew a Wirraway with Sid on a low level navigation exercise. Weflight planned from Uranquinty to Tocumwal, which was a RAAF airfield on the NSW andVictoria border. In those days, the airfield was a vast storage depot for war surplusMustangs, Liberators, and other types. Sid had done this trip with his other students, andhaving noticed the absence of guards around the base, he decided to liberate thenavigator's astrodome on a Liberator (I thought "liberate" was a neat choice ofwords), and use it as punch bowl at home. We flew at 200 feet across the countryside, andafter landing Sid disappeared armed with a crash axe and screwdriver. While I kept an eyeopen for roving guards, Sid found a suitable Liberator and — wary of red-back spiders —carefully removed the astrodome.

The immediate problem was where to stow it in the Wirraway. It was too bulky to fitthrough the fuselage access door, so one of us would have to hold it on our lap in flight.This was solved by Sid removing the instructor's detachable stick from the rear cockpit(which was normal procedure for solo flying from the front seat) and flying as apassenger, rather than as an instructor.

After clipping on his parachute, and settling awkwardly into the rear seat, he managedto wrap both arms around the precious astrodome and hold it on his knees. I strapped intothe front seat and started the engine. With the rear control column stowed, Sid warned methat I was in command and for Christ's sake don't prang the aircraft, as there was no wayhe could take over control if something went wrong. Making the flight with theinstructor's controls disabled was a potential court martial offence, and so probably wasthe removal of an astrodome from Her Majesty's Liberator bomber! Sid, however, wasdetermined to have his punch bowl.

The flight home at 200 feet was uneventful, and I had almost forgotten that Sid wasaboard until a quiet voice from the rear seat exhorted me to land real carefully and trynot to ground loop after touch-down. To our mutual relief, the landing was a smooththree-pointer on home turf, and afterwards Sid wrote in my hate sheet (student pilotprogress report) that I was now qualified to carry out solo, low level navigation flights.

An RAAF Pilot...At Last

After graduation from Point Cook, I did a short spell on Mustangs and Vampires beforebeing posted to fly Lincolns with No.10 Squadron at Townsville. The Lincoln was a morepowerful version of the well known Lancaster four engine heavy bomber. Among the aircrewwere veterans of bombing raids over Europe, including navigators, gunners and radiooperators wearing the gold eagle badge of the Pathfinders. While collecting my tropicalkit and parachute at the clothing store, I was surprised and delighted to run into SidGooding again. He had been with the squadron for a few months as the QFI and wasresponsible for the conversion of new crews to the Lincoln. He congratulated me onreceiving my pilot's wings, and said I was on the roster to fly with him on the Anzac Dayceremonial fly-past over several North Queensland towns.

After graduation from Point Cook, I did a short spell on Mustangs and Vampires beforebeing posted to fly Lincolns with No.10 Squadron at Townsville. The Lincoln was a morepowerful version of the well known Lancaster four engine heavy bomber. Among the aircrewwere veterans of bombing raids over Europe, including navigators, gunners and radiooperators wearing the gold eagle badge of the Pathfinders. While collecting my tropicalkit and parachute at the clothing store, I was surprised and delighted to run into SidGooding again. He had been with the squadron for a few months as the QFI and wasresponsible for the conversion of new crews to the Lincoln. He congratulated me onreceiving my pilot's wings, and said I was on the roster to fly with him on the Anzac Dayceremonial fly-past over several North Queensland towns.

When we met, he was exchanging a scorched and battered flying helmet and goggles for anew set. On seeing my raised eyebrows, he pointed across the airfield to the burnt outwreckage of a Lincoln bomber. Sid had been converting an experienced Dakota pilot andwhile demonstrating a landing with one propeller feathered, he got into difficulty whenthe aircraft drifted off the runway just before touch down. Sid decided to go around, andapplied full power on the remaining three Rolls Royce engines. Even with full rudderapplied, he was unable to stop the Lincoln from yawing into the dead engine. He managed tokeep it in the air for the next 20 seconds before the left wingtip hit a power pole andspun the huge aircraft into the ground. The three crew members managed to escape from thewreckage before it went up in flames. The only casualty was the radio operator who brokehis nose during the final impact. Just before the plane blew up, Sid decided to return tothe wreckage to find his wallet, which had dropped from his pocket as he ran. Fortunately,he had second thoughts on the matter, because 2,000 gallons of fuel from the rupturedtanks ignited a few seconds later.

Sid returned to the scene of the accident the next day, and posed for the unitphotographer. The photo was a classic. It reminded me of the scene of a lion hunterposing, rifle in hand, and with one foot placed triumphantly on the dead beast. In thiscase Sid had one foot on the wreckage of the Lincoln, his pipe in hand, and service capjauntily tilted on his head. The caption was "All my own work!"

Building Time

When I first arrived on the squadron, I had 280 flying hours in my logbook. Thecommanding officer briefed me that I could expect to fly as a second pilot for nine monthsbefore being given a take off or a landing. At the end of that time, I would be then bechecked out to fly in command on local flying. At a later stage, I would be given my owncrew (consisting of seven men) and become qualified to take part in anti-submarineoperations. Contrast this with the major airlines where seniority ruled supreme and 15years to first command was the norm.

While building hours on the Lincoln, I flew with captains of varying abilities, but myfavourite was always Sid Gooding. In later years as an instructor, I tried to model my owntechnique around his patient and laid back approach. His helpful attitude was in markedcontrast to that of the many supercilious and pompous check captains that I encountered inmy airline career.

Anzac Day

It was Anzac Day 1953, and Sid and his crew (with myself as second dickey) got airbornein Lincoln A73-10, for a fly-past over North Queensland country towns. It would culminatein a low run down the main street of Cairns over the marching war veterans. Seconds afterliftoff, the starboard outer engine lost cooling glycol, and Sid asked me to feather thepropeller. It was inconceivable that we should turn back and abandon the fly-pasts, and inany case the RAAF reputation depended on our presence in the skies over North Queenslandon this day of national importance.

We flew over several country towns with No. 4 engine feathered, finally passing lowover the Cenotaph at Cairns, dead on time. Engine failures on the Lincolns were notunusual, and I became quite used to flying with one engine stopped.

One day, Sid gave me the controls for take off. I was delighted to have a go, andmanaged to keep straight with much juggling of throttles and rudders. The Lincoln was atailwheel aircraft, and therefore prone to swinging both on take off and landing. Thetechnique was to lead with both port throttles until the rudders came effective, thenincrease to full power on all four engines. As the tail came up, gyroscopic forces actingthrough the propellers, were countered with judicious use of rudder. I had been used tothis in the Mustang, so it was no big deal to keep the Lincoln straight down the runway.However, as this was my first take off in a Lincoln, Sid talked me around the circuit andwith quiet encouragement and also talked me through my first landing in this big bomber.It bounced a few times, but ran straight and I felt on top of the world.

In that era it was considered good manners to thank the captain for giving away thelanding, although that old world courtesy seems to have disappeared in modern times.Certainly I never saw it happen in the airlines. As we taxied back, I thanked Sid for thetake off and landing. "That's quite alright, Sergeant," he replied, "It wasa pleasure."

Forty Years Later...

The years passed, and I heard that Sid had left the RAAF to become a schoolteacher.Faced with the inevitable desk job, I too regretfully left the RAAF after 18 happy years.The pages of my logbooks filled up with civilian flying hours with the airlines, and onreaching age 60, I was faced with compulsory retirement from flying Boeings. To earn acrust, I renewed my instructor rating and did occasional work as a flight simulatorinstructor.

Then, from a colleague came the news that Sid had retired from teaching and lived inNumurkah in country Victoria. I found his address and was soon on the phone. His voicebrought back happy memories of our flights together nearly forty years ago.

Sid was nearing 80, and his eyesight was fast fading. He welcomed my suggestion that Icould fly up to see him, saying that he would arrange a picnic for my arrival at a nearbyairstrip. The next day was sunny, and I track crawled at 2,000 feet to Numurkah. None ofthis one-in-sixty rule for me!

Circling the airstrip, I could see two people with a car waiting in the shade of sometrees. The wind was calm and the touch down slightly bouncy. After many hours in Boeings,I still had trouble nailing the round out in light aircraft.

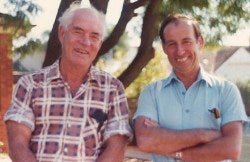

Piper Cherokee |

As I climbed from the Cherokee, I recognized Sid immediately. He looked younger thanhis real age, although by now his hair was white. Having said that, I felt conscious of myown balding head and middle-aged spread. We talked of old times, and I mentioned that Ihad a photograph of him standing on the wreckage of his crashed Lincoln. He asked me toexamine the photo closely to see if his wallet was there. I thought that with time, I musthave imagined the story of Sid's wallet, but happily it was still true.

While Doreen his wife arranged the sandwiches and tea, I finally asked Sid how he wonthe DFC. He said that he had been on a 1,000-bomber night raid over Germany when anotherLancaster collided with his aircraft. With part of the right wing torn away and theoutboard engine demolished, Sid needed full rudder and aileron to hold altitude. Heconsidered jettisoning his bombs and returning home, but realized that this meant flyingback into the outbound bomber stream. A midair collision was a near-certainty in the dark,so he decided it would be safer to continue to the target with his crippled Lancaster thanrisk a turn back. His big worry was that if a German night fighter locked on to him, hewould be unable to take evasive action. In the event, he dropped his bombs on the target,and returned safely after flying seven hours with full control deflection. For this he wasawarded the DFC.

Taking Sid Up

|

As we talked, it was clear to me that his eyesight was bad, because he was unable tosee the photographs that I brought with me. He told me that his wife read books to him,and that sometimes he obtained talking books from a Melbourne library. The time came tosay farewell, and on impulse I asked Sid would he like to come on a short joy flight withme before I left for Melbourne. He was delighted with the idea, and after helping him onto the wing of the Cherokee, I soon had him strapped into the left seat. His wife politelydeclined my invitation, and told me quietly that Sid had hoped that I would offer to takehim up.

|

There was no way that Sid could see the instruments clearly, although he could discernthe horizon as a general blur between sky and ground. I started the engine and, afterreleasing the brakes, asked Sid to taxi the aircraft. By giving him general directions —left rudder for five seconds, right rudder for two seconds, now rudder central — wetaxied to the end of the field and lined up for take-off. I could see Doreen watching fromthe trees.

The Cherokee is a simple training aircraft, and with Sid at the controls I asked him ifhe wanted to do the take off. "Just keep an eye on me, and give me directions,"he said, and off we went. I gave him a few minor corrections to keep straight and as wereached rotate speed, I called for him to place the nose just above the horizon. He flewby instinct and experience, holding the attitude just right.

He could not see either the altimeter or airspeed indicator, so I told him to level outwhile I set the throttle. He held attitude accurately despite seeing only a blur. His turnto downwind was smooth and beautiful to watch, and I found myself going back in time whenI had watched Sid execute a perfect asymmetric circuit after we had lost the engine onAnzac day in 1953. I asked him could he see the airstrip now on his left. He had no hope,he said. Would he like to do the approach and landing, I said. He said he would happy togive it a go, but would need steering directions on final. By this time we had gone a fairway downwind, and I lost sight of the grass strip behind us. Talk about the blind leadingthe blind!

Talk-Down

In the RAAF, we used to fly practice GCAs (Ground-Controlled Approaches). These wereradar approaches conducted by ground controllers, sometimes known as"talk-downs." The controller sat in a radio truck and guided the radar targetdown the course and glidepath marked on his screen. As the aircraft came over thethreshold, the radar controller would say, "Touch down, touch down ... NOW!" andseconds later the wheels would hit the runway. GCAs were very effective in thick fog, butunreliable in heavy rain due attenuation of the radar screen. Today there was no fog orrain — just a fine sunny afternoon and perfect for a GCA. But first I had to locate thestrip again.

In the RAAF, we used to fly practice GCAs (Ground-Controlled Approaches). These wereradar approaches conducted by ground controllers, sometimes known as"talk-downs." The controller sat in a radio truck and guided the radar targetdown the course and glidepath marked on his screen. As the aircraft came over thethreshold, the radar controller would say, "Touch down, touch down ... NOW!" andseconds later the wheels would hit the runway. GCAs were very effective in thick fog, butunreliable in heavy rain due attenuation of the radar screen. Today there was no fog orrain — just a fine sunny afternoon and perfect for a GCA. But first I had to locate thestrip again.

I told Sid I would talk him down like a GCA controller using RAAF terminology withwhich we were both familiar. He had flown radar controlled approaches in Mustangs andSpitfires, so he was no stranger to the technique. Sure, he lacked currency after fortyyears, but he could still pick an attitude despite being partially blind.

His circuit height was remarkably accurate as I asked him to add more or less power tomaintain cruise airspeed. Finally I spotted the strip and turned Sid on to long final. Heheld the nose attitude admirably as I gave him heading instructions to keep the airstripdead ahead. I warned him of the trim change with lowered flaps, which he fixed with thetrim wheel after a little groping. I told him that when round-out was imminent, I wouldcall him to flare and close the throttle. From experience, he knew the rate at which tokeep coming back on the wheel during hold off. Any problems, I told him, and I would takeover control. Thirty seconds to round-out, and I could see Doreen walk from the shade ofthe trees to watch the landing. I think she knew that Sid would be on the controls.

"Five, four, three, two, and flare NOW, Sid," I called, and held my breath,my hands poised close to the controls. "Six inches above the grass, Sid ... hold itthere." Sid held off beautifully then greased it, maintaining the aircraft right downthe centre of the strip. I asked him to apply the brakes gently, and as we slowed down Itook control for the 180-degree turn. We taxied back to the trees and shut down theengine. After the propeller had stopped and I switched off the ignition, my mind went backin time to when Sid had given me my first landing in a Lincoln. I was glad that I couldreturn the favour, albeit forty years later. For me, it was a touching moment, and whileSid happily told his wife about his landing, I busied myself with a walk around beforedeparture.

Then we shook hands and said our farewells. As I settled into the cockpit of theCherokee, Sid touched me on the shoulder and said, "Thanks for the landing,John". "That's alright, Sid," I replied. "It was a pleasure."

NOTE: Sid Gooding just celebrated his 84th birthday. John Lamingwrote this story as a birthday present for his old military instructor. Can you imagine amore thoughtful gift?