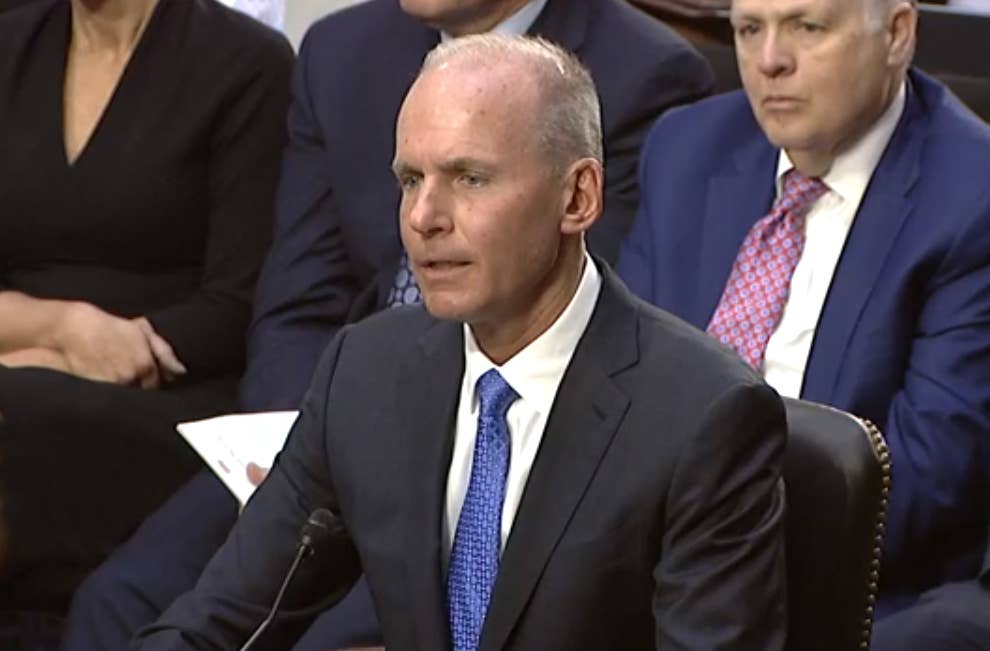

Senate Committee Questions Boeing CEO On MAX Safety

The Senate Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation grilled Boeing CEO Dennis Muilenburg and Boeing Commercial Airplanes Chief Engineer John Hamilton on “actions taken to improve safety and the company’s…

The Senate Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation grilled Boeing CEO Dennis Muilenburg and Boeing Commercial Airplanes Chief Engineer John Hamilton on “actions taken to improve safety and the company’s interaction with relevant federal regulators” during a Tuesday hearing related to two fatal accidents involving Boeing 737 MAX aircraft. The hearing, titled “Aviation Safety and the Future of Boeing’s 737 MAX,” took place in the wake of last week’s publication of the final report on the Oct. 29, 2018, crash of Lion Air Flight 610. The Boeing 737 MAX has been grounded since March following the crash of Ethiopian Airlines Flight 302.

“While the Ethiopian Airlines accident is still under investigation by authorities in Ethiopia, we know that both accidents involved the repeated activation of a flight control software function called MCAS, which responded to erroneous signals from a sensor that measures the airplane’s angle of attack,” Muilenburg said in his opening statement (PDF) to the committee. “Based on that information, we have developed robust software improvements that will, among other things, ensure MCAS cannot be activated based on signals from a single sensor, and cannot be activated repeatedly. We are also making additional changes to the 737 MAX’s flight control software to eliminate the possibility of even extremely unlikely risks that are unrelated to the accidents.” Muilenburg reported that Boeing has logged more than 100,000 engineering and test hours on “improvements to the 737 MAX,” along with flying at least 814 test flights with the updated software and conducting simulator sessions with 545 participants representing 99 Boeing customers and 41 global regulators.

Senators also questioned Muilenburg on the recent emergence of communications from Boeing staff that suggest the company may have been aware of potential safety issues with the aircraft’s Maneuvering Characteristics Augmentation System (MCAS) and that there might have been some attempt at hiding those issues from regulators during the certification process. Muilenburg told the committee that he had only recently been made aware of the documents in question, including a 2016 instant messenger exchange between Boeing’s 737 MAX chief technical pilot Mark Forkner and a colleague describing the MCAS as “running rampant in the sim” and the aircraft as “trimming itself like crazy.” As previously reported by AVweb, FAA Administrator Steve Dickson sent a letter to Muilenburg on Oct. 18 demanding an immediate explanation for the contents of that document and Boeing’s delay in bringing it to the FAA.

Further inquiries were made by the committee into Boeing’s relationship with the FAA and the Organization Designation Authorization (ODA) program. In addition, the committee heard from NTSB Chairman Robert Sumwalt and Chairman of the Joint Authorities Technical Review (JATR) Christopher Hart on their work surrounding the MAX. Sumwalt spoke on recommendations published by the NTSB in September regarding the effects of multiple cockpit alarms and what can happen when pilots don’t react as expected to emergency situations. The recommendations were the result of investigations into the MAX accidents.

Hart discussed JATR’s final report (PDF), issued in October 2019, which calls for “reviewing whether the ODA process can be made less cumbersome,” ensuring adequate communications in the certification process, and “revisiting the FAA's standards regarding the time needed by pilots to identify and respond to problems that arise.” JATR was chartered by the FAA in June 2019 to conduct an independent review of the certification of the Boeing 737 MAX.

The complete hearing can be viewed on the Senate Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation’s website. According to Committee Chairman Roger Wicker, R-Miss., additional hearings on the 737 MAX will be held.