Pro pilots tell us that it’s not the difficulties we train for that will get us. It’s the ones we can’t train for. Here are seven examples of IFR pilots who coped with the unexpected. What would you have done?

Too Much Tech?

A Beechcraft V35 departed VFR at dusk with rain squalls in the area. The pilot elected to obtain his IFR clearance airborne before climbing into darkening sky. Crossing 2000 feet, ATC cleared him on course direct. Then he noted that his GPS had dropped out.

The Bonanza had recently been updated with an Aspen 1500 and a Garmin GTN 650. The GTN was interfaced via a Flightstream 210 wireless connection to an iPad mini on the yoke running Foreflight—a well-equipped IFR avionics panel. The GPS signal returned in about 30 seconds. Still VMC, he debated remaining VFR or aborting his flight. The GPS loss seemed like a glitch. ATC said no one had reported an outage. Ultimately, he elected to continue IFR into rain, cloud and turbulence up to 8000 feet.

Suddenly the GPS not only failed again, but the ADS-B In failed, and multiple error messages began spewing from the GTN. Counting on his yoke-mounted iPad with Foreflight, he figured he could continue in heading mode and navigate via ATC. He soon realized that the iPad data had been corrupted by the erroneous GPS data from the GTN 650. Once the pilot disconnected the iPad from the panel, the panel settled down.

It is possible there was too much connectivity between the GPS, ADS-B In, heading and tablet software. It also seems that this installation was new or nearly so. Any new panel should be wrung out thoroughly before tackling IFR.

GPS Malfunctions

A bizjet crew realized something was wrong on approach when their FMS began issuing error messages including “VOR-GPS disagree” and “FMS DR”—meaning the FMS had fallen into dead reckoning mode. Looking outside, they were much closer to the airport than the FMS claimed. They advised ATC and received vectors for the remainder of the approach.

In another case, ATC gave an aircraft a heading and cleared them to FRAME intersection (at the time) after departing KFAT in Fresno, California. Even though the aircraft appeared to turn correctly, ATC asked if they had turned toward FRAME yet. The crew declared it had lost the GPS and asked for vectors. The GPS never recovered, so they navigated with vectors and VORs to the destination. The pilots might have recognized the GPS issue before departure, but it seems they did not check it at that time.

Jamming can cause pilot saturation. One pilot reported multiple routing changes due to GPS outage advisories, distracting the crew and precipitating several clearance deviations. Another aircraft reported a GPS outage, causing the autopilot to revert to PITCH and ROLL modes. Busy dealing with the autopilot, the crew misunderstood ATC and mistakenly began a descent. Shortly thereafter, GPS returned to normal.

Approaching White Sands Testing Area in New Mexico, ATC warned a pilot of “radar jamming” affecting GPS. Soon afterward, both GPS units lost position reporting for the remainder of the flight.

These experiences tell us to be aware of testing, which can play hob with GPS. If a GPS TEST NOTAM is issued, be prepared for unusual panel events. High workload and frequent flight plan revisions can trigger pilot saturation, confusion and pilot deviations. En route, back up GPS with VOR when able.

Where’s Here?

A Piper Arrow was on a VFR flight when its GPS failed. In-flight troubleshooting also failed. The pilot elected to land and correct the issue. Spotting an airport with two runways, but unable to identify it, the pilot landed.

After parking, the pilot noticed many people in uniform. After speaking with a police officer, he found he had been in a restricted area and worse, he had landed at a military base. The pilot’s idea of resolution centered on his instructor’s post-event recommendation to shut all the avionics off and restart. He added that he should have requested flight following through the area.

Somehow this instrument-rated pilot managed to forget that his Arrow had two VORs, which he could have used to locate himself. This may be a dying art, but it works. A much better idea than time in the brig.

Random Heading Indicator

During an instructional IFR flight in IMC, ATC requested the 182 turn to a heading of 360. Moments later, ATC called saying they had turned too far and to return to heading 360. Verifying the heading against the compass, the HI was off. The instructor reset it, but ATC again complained that it was off. The HI was not working. When the attitude indicator began to roll over, the crew realized they had suffered a vacuum failure. The instructor informed ATC and requested vectors to their departure airport. ATC gave them no-gyro turns and vectors. Once in VMC, they canceled IFR and landed.

The instructor chided himself for not having suspected vacuum system failure sooner. He was also upset because he missed several ATC calls while troubleshooting. In such a situation, it seems that troubleshooting is more important than talking on the radio to someone who can’t help you fix it.

Too Much IFR

An instrument-rated pilot was planning to land at KVAY in Mount Holly, NJ. Navigating VFR, he received flight following for the 15-minute flight.

Turning right downwind to base for runway 26, he instead lined up with runway 19 at Flying W airport just two miles away. Landing on runway 19 he realized his error when he saw another airplane facing him at the far end of the runway. Someone said “Isn’t runway 1 the active?” on the CTAF. Rattled, he back-taxied to runway 1 rather than exiting the runway. He departed and landed at KVAY minutes later.

He admitted that he was rusty with VFR, noting that IFR is often easier than VFR. During preflight, he should have known of the nearby airport. On final, he would have seen his error had he but looked at his heading. While the runway numbers were very faded, they were still readable.

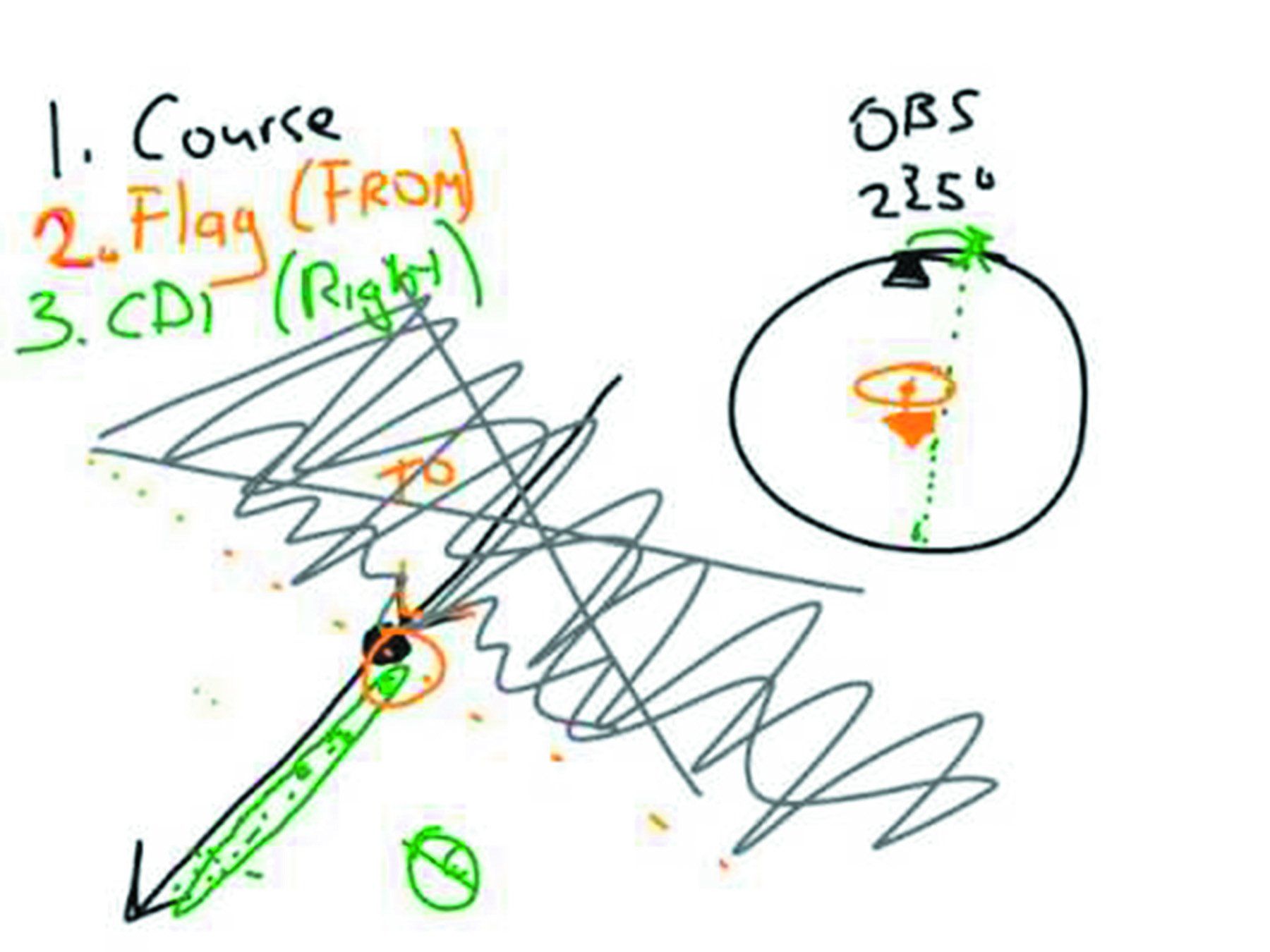

Even better, he could have used his GPS to verify that he was landing at KVAY. The VFR Sectional reveals a cluster of four airports in the vicinity. Many pilots use OBS mode to set the centerline of the desired runway or enable the runway extension feature in many MFDs to prevent this kind of error.

Altimeter Antics

On an instructional IFR flight, the Cessna was flying the RNAV 25R approach at KLVK in Livermore, CA. ATC alerted the aircraft that it was below altitude for that approach segment and to stop descending. Crosschecking, the analog altimeter was reading 300-400 feet higher than what ATC was receiving via the transponder’s Mode C. They stopped their descent, reset the altimeter setting issued by ATC and checked the alternate static air in case of a blockage. No change.

Even so, and perhaps unwisely, the aircraft requested a low approach. Tower said he was in a “quandary” as to whether the Cessna was canceling IFR. However distracting, the situation could have become critical with two safety issues in progress. The aircraft completed its low approach and received more cooperative service from Approach en route to home base.

The pilot later learned that there had been a significant rainstorm for the past 2-3 days with heavy winds and downpours that could have allowed water to enter the static port. Having a misreading altimeter, especially high, is dangerous. A better choice would have been to scrub the approach and go home, relying on ATC for altitude.

The Mode C readout is pressure altitude, based on 29.92 inches of mercury. Usually it’s close to the altimeter if the pressures are similar, and therefore a good backup.

The Panicked Passenger

Flying two passengers to TruckeeTahoe Airport in California, one passenger asked to fly right seat and be given a headset; the pilot agreed. His plan was to overfly KTRK and cancel IFR if it was VMC. While unable to see the airport from altitude, the AWOS was reporting ten miles and clear. Noting a large clear area over the valley, the pilot canceled IFR and advised ATC that he would descend and turn to KTRK. ATC advised of another aircraft several miles away on the RNAV 20 approach to KTRK.

With the AWOS holding, the pilot began to descend. At about 7200 feet and 3-4 miles from KTRK, he was suddenly engulfed in a whiteout condition just as the other aircraft declared a missed approach. He elected to make climbing turns over KTRK and then divert.

The passenger riding shotgun panicked. Extremely distracted, the pilot flew the aircraft into an accelerated stall due to over-banking while turning. The pilot coolly pitched down to recover, re-established his climb and diverted to his alternate.

Recalling The Learning Events

Having been acquainted with the IFR system for well over 40 years, I sometimes forget how it was as a fledgling pilot in the early days. However, it doesn’t take too long, especially when providing dual for the Instrument Rating, to bring back some of the events that shaped my thinking and my reaction philosophy to the environment.

The first time you’re faced with navigation failure can bring a cold chill down the spine, especially if the approach you are executing is to a non-towered airport that didn’t provide direct ATC communication. When you’ve descended below their line-of-sight, and radar contact is lost, you’re on your own. What would your first response be—the miss?

How many minutes—or seconds is your initial troubleshooting effort, before you realize that there are some pretty tall mountains/towers out there and you need a plan of action—quickly.

The realization of instrument failure is another awakening moment. This one came as I was departing and had just poked my nose in the clouds and had started my scan. Here I had “the voice” of the tower, but there was nothing they could do, it was all up to me.

So what is your strategy for addressing a critical failure? Certainly, there is no substitute for knowledge and proficiency. But there is also that ability to keep hold of your emotions and fly the plane.

—Ted Spitzmiller

Fred Simonds, CFII, lives in south Florida. The above events were selected and condensed from the ASRS Report Set on GPS.

This article originally appeared in the October 2018 issue of IFR Refresher magazine.

For more great content like this, subscribe to IFR Refresher!