I suppose as analogies go, using fruit and baked goods is as good as any to describe the state of the general aviation market. A decade ago, it was sugar plums. Now it’s pies or, to be more accurate, pie in the singular.

About 2005 or so, but definitely by 2007, every GA manufacturer of any size—and many small ones—had or was considering a “China plan.” That’s because China was then seen as a potential bottomless pit of airplane demand, a teeming mass of humanity whose individual and collective hearts throbbed with an unquenchable desire to fly airplanes. Thus the sugar plum analogy.

Ten years later, we’ve come down off that sugar high and accepted that sales of airplanes are, at best, flat, if not in decline globally. The pie isn’t getting any bigger, so companies are angling for a bigger slice of it. Continental’s Rhett Ross put it in more or less those exact words when I interviewed him recently at the company’s Mobile headquarters.

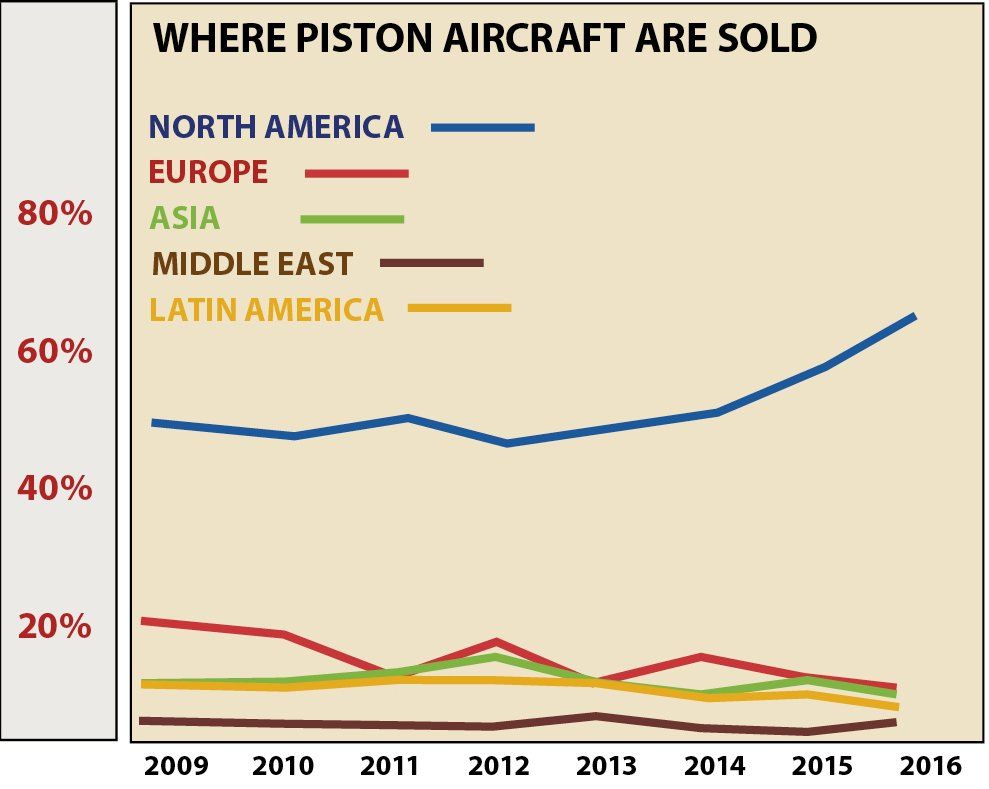

And now, something new: How about a North American plan? The argument for that is seen in the graph here. I couldn’t find good data prior to 2009, but since then, the North American share of the pie has gotten markedly larger while ever other region’s is trending slightly smaller, according to GAMA’s data.

Why is this so? It’s both obvious and not obvious. North America is where the money is, gas is cheap here, regulation is minimal (it’s all relative) and the world comes to the U.S. to learn to fly. There are currency issues; through the 2005 to 2008 period, the dollar exchange against the Euro was as high as 1.5 to the Euro. It’s now at 1.12. Jets and turboprops are almost exclusively business-use aircraft, but so are some pistons and that’s more likely to be the case in the U.S. than anywhere else in the world. And given that the U.S. economy is outstripping at least some of the western industrial economies, there’s just more business activity here. When you’re selling only 1000 piston airplanes a year, it doesn’t take much of that to move the needle a little.

Cirrus, Cessna and Mooney probably have this baked into their thinking, so their default is to sell in North America. The Austria-based Diamond has noticed the trend and that’s the very reason the recently announced DA50-VII will have a Lycoming TEO-540 as a primary engine and diesel as an option. Diamond’s Christian Dries recently told me that’s what will sell in the U.S. and that’s where the larger slice of pie will be found. I knew the data supported his supposition, but until I graphed it out, I didn’t realize how dramatic the swing has been.

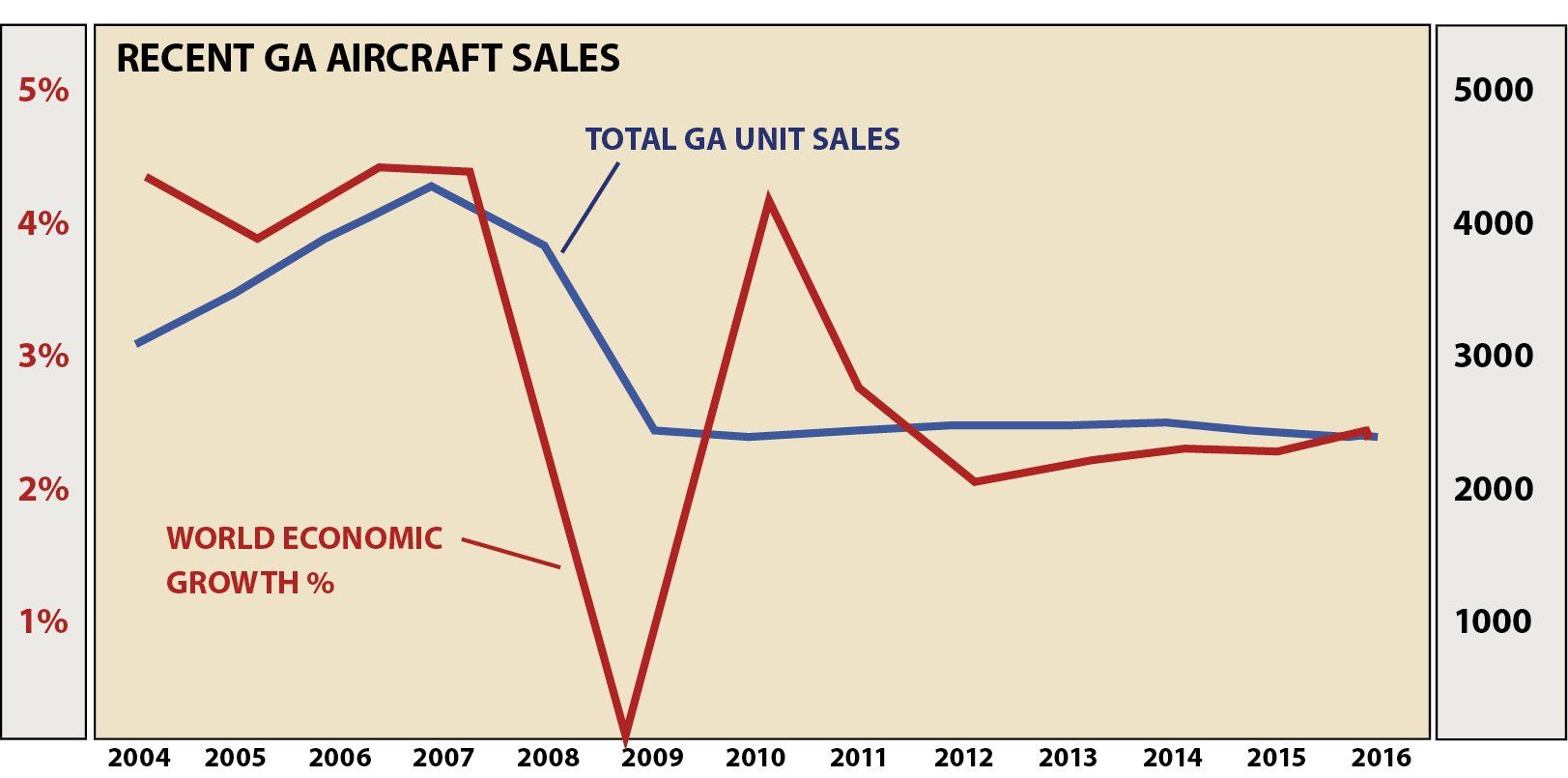

I also took a look at longer trend lines in GA sales. We tend to obsess about GAMA’s quarterly sales reports, but the second graph shows why we shouldn’t. Total GA output—that’s everything from pistons to jets—has been essentially flat since 2009. There was a little bump in 2014, but current sales have hovered around 2200 airframes a year or just over 50 percent of the last high-water mark in 2007, which was 4276 aircraft.

That was a full decade ago, which is why you don’t hear people talking about “recovery” anymore since the realization has set in that the cycle has probably extended beyond the normal business swing. No one can say for sure, but if we’re ever going to reach 4000-plus airframes again, the market forces that will do that seem to be well camouflaged. But turn the question on its head and ask if 2007 was just an aberration, a fluky peak never to be repeated.

Maybe. But there must have been a reason for it. In an otherwise stagnant market for anything, new products stimulate sales and that’s probably true of airplanes, too. Two things were new in 2005, when the sales peak was becoming visible: the widespread availability of glass cockpits and Diamond’s DA42 diesel twin, which found latent demand in the training industry. Since then, we’ve had iterative improvements, but no major product introductions. The Cirrus jet and Diamond’s DA60 may be innovative enough to bump the numbers some. We’ll see.

Just as a curiosity, I plotted world GDP growth against aircraft sales. As you can plainly see, there’s loose correlation, but definitely loose. It’s strongest in the flat part of the curve since 2009. I also looked at the first-quarter sales extending back to 2004. GAMA’s first-quarter report for 2017 seemed to show a bright spot; sales were up 6 percent over the same period in 2016. While that’s good news, I don’t think it means much.

Since 2009, there have been first quarters better than that and worse than that. The average for that period is 383; the mean 371. I think in context, it’s just noise in the data. Absent any other changes or data, I think that curve sketches a sea change. The market is now trending more strongly toward replacement of training aircraft than it did from 2005 to 2007. There’s still enough wealth out there for private owners to write $500,000 checks for new airplanes, but are we more likely to find fewer rather than more of them? I think the former for the short term. Until, of course, all those Chinese wake up to the fact that they’re burning to fly airplanes.

You’re welcome to post your own theories in the comments section.