Canada’s Transportation Safety Board says Diamond Aircraft’s factory maintenance staff mis-rigged the rudder cables on a DA42NG, contributing to an accident that heavily damaged the twin. In its final report the TSB said the plane, registered to the company’s U.S. sales division, was on its post-maintenance test flight on May 25, 2022, when it yawed left on takeoff and the pilot was unable to properly control it. The aircraft landed heavily on the grass at London Airport, where Diamond Aircraft has its North American headquarters, and was badly damaged. The pilot suffered minor injuries. Diamond did not immediately respond to an after-hours email request for comment, but we will publish its response if it is forthcoming.

Examination of the aircraft revealed that rudder cables had been installed incorrectly after some worn control cable guide tubes were replaced during heavy maintenance of the aircraft. The plane was undergoing a 2,000-hour inspection and overhaul, which involves partial disassembly of the airframe, replacement of the engines and general refurbishment of the aircraft.

The TSB report said the worn tubes were discovered by an apprentice mechanic who was then tasked with replacing them. When he put the system back together again, he set up the cables incorrectly and that resulted in the rudder moving in the opposite direction to control movements. “This was the first time the apprentice changed the rudder cable guide tubes on a DA 42 and he was not aware that they had to cross over each other,” the report said. “The apprentice’s previous experience with rudder controls at Diamond Aircraft Industries Inc. was on a DA 20 aircraft. The rudder cables on that aircraft run parallel to each other.”

The TSB said the guide tube snag was not properly documented and the mechanics who oversaw the apprentice did not give him guidance in the correct configuration of the control cables. “The team lead did not provide the apprentice with any reference material, such as the manufacturer’s installation drawings,” the report says. “The team lead also did not ensure that the apprentice knew and understood that the rudder cable guide tubes crossed over each other in the rear fuselage, as described in the AMM.”

The TSB said the pilot did a thorough preflight inspection but it’s difficult for the pilot to see the rudder when checking control movement and he did not notice that the rudder moved opposite to control inputs.

One major thing you do when an aircraft has been in for maintenance is review the scope of work that was done and then pay extra attention to those systems. Regardless of the scope of work a basic flight control check with visual verification is a must!

How is this even still a thing that catches pilots unaware?

These things called ‘humans’

No, the accident was because a pilot did not TEST correct movement of the surfaces before the first flight after the control cables were removed and replaced. Never, ever just haul off and fly after “heavy maintenance”. I’m sorry but this was 100% preventable.

Arthur, you are correct.

Yes Arthur, you are correct. And whatever happened to “thou shall use the Maintenance Manual” rule? The local FAA made us have the current data at our tool boxes!!

Pilots check “free and correct” on EVERY preflight, because your life depends on that (maintenance or not).

Precisely, Mr. Raf Sierra.

First of all , this type of work has to be done by a trained and licensed mechanic , ( they cost more money) 2 . He has to perform a flight control check with a second person outside with knowledge! ( more money!) 3. A pilot with knowledge and a person with knowledge outside has to perform a 2. flight control check !!

4. A test flight has to be performed after all flight control and power malfunction or work ! But that cost more money! We want to have everything cheap as possible, the company management has to react or they are out of business . So ho is guilty ?

Cost? We see again what it costs when a pilot does not do his preflight.

The mechanic failed to assemble the aircraft correctly, the supervisor failed to inspect the mechanic’s work or ensure he had proper manuals to perform the work. The pilot then failed to do a proper control check, which would require someone in addition to himself.

Smells like Swiss cheese.

You blame greed, but I’m going with sloth.

I’m inclined to back up and ask why the design had the cables crossed in the first place. I can’t think of a single aircraft having only one rudder, where the cables cross. That seems to be just asking for trouble. And yes, there were multiple points where the error could have been caught, but why leave a landmine just off the path?

Irregardless of the complexity of the design on the rudder system of this DA42 or on any aircraft, be it rudder torque tubes and cable routing, the mechanics are required to reference design docs and pictorials in the respective Mx manuals and have them at their work station and use them, with the lead mechanic overseeing the entire work order and supervising any apprentices.

Then, final oversight and inspection and checklist completed, documented.

Apparently none of this was done.

Total nonchalant complacency here on the part of Diamond Aircraft Mx .

The Canadian TSB didn’t mince their words in their final report .

As was stated before, ” Shade Tree ” style operation here from an aircraft manufacturer and Mx Department no less.

This plane was designed before the Chinese buyout. It was probably done to reduce complexity and weight while offering better feel for the pilot. If it was considered an unsafe design, I doubt Diamond would have done it. They could have easily made the plane many knots faster, and sold many more of them, but they did not.

Yes, this should have been caught during QA checks and preflight, but the more disturbing thing is this was a “factory refurbishment” not ref’ing procedural docs with leads being part of the problem…shade tree mechanic “stuff” that how many customers were paying extra for.

…or maybe they’ve just taken on Boeing/Spirit corporate processes.

Agreed

Never ever short cut checks after maintenance. Reminds me of when I picked a King Air 200 up from annual. Going through the rudder boost check, found it was working backwards. Seems the pneumatic lines were reversed.

How many thousands of times had I done that check and it worked correctly? What would’ve happened if I’d lost an engine on rotation like that?

Trust no one

Poor design imho. Tubes should be different sizes, have different threads, something. Fuel gasses (propane, acetylene) all have left hand threads for a reason. Pc computers, since almost day one, if the cable doesn’t plug in there, it’s not supposed to plug in there.

Bad design? Reminds me of Piper Aircraft getting sued because of the “bad design” of the J3 having bad forward visibility on the ground.

Never heard of that one —

” Piper to be sued because of poor forward visibility in a J3 Cub ” while in ground ops…

They should have included C.G.Taylor and Walt Jammaneau if that is true.

Cleveland v. Piper Aircraft.

Just read that one online, WOW, talk about a “Stupid Pilot” and Piper paid the bills. Thank you stupid Judges.

Good comment- even different colors for left and right etc

You can only make it “Idiot Resistant” not “Idiot Proof”…the truly determined idiot will find a way around those parts that won’t go together…and they self-identify, they’re the one not using the maint manuals.

Takes a determined idiot to get jet fuel in a recip, but hand him a funnel and he’ll get right on it.

Well ,as Jennifer Homandy of the NTSB said recently:

” If there is human error, there usually means the system itself is broken and needs redesign.”

Human error, is the root of most errors. Humans are the system designers as well.

The system consists of maintenance manuals, training, and inspections. None were used in this case.

Complacency. Use of maintenance manuals (lack of). Insufficient oversight. Lack of proper task verification. If the pilot cannot properly see control movements pre-takeoff due to the design, the previous pointers become essential.

One would think that by now design criteria for these kind of systems are required to limit cross-control installation. There have been numerous high-profile accidents due to this (simple) flaw.

Wake-up everybody!!

Every time I have picked up an airplane out of maintenance that had flight controls worked on, I visually check the control direction with another person at the controls. It takes at least a second person to do this. This is before powering up the plane. Too many accidents out there where the controls were connected wrong by mistake, at least wrecking the plane or killing all onboard!

I’m surprised that no operational checks done. Even if it isn’t stated, always a good idea to do after critical systems work. In my case, it is probably a legacy of my USAF Crew Chief days.

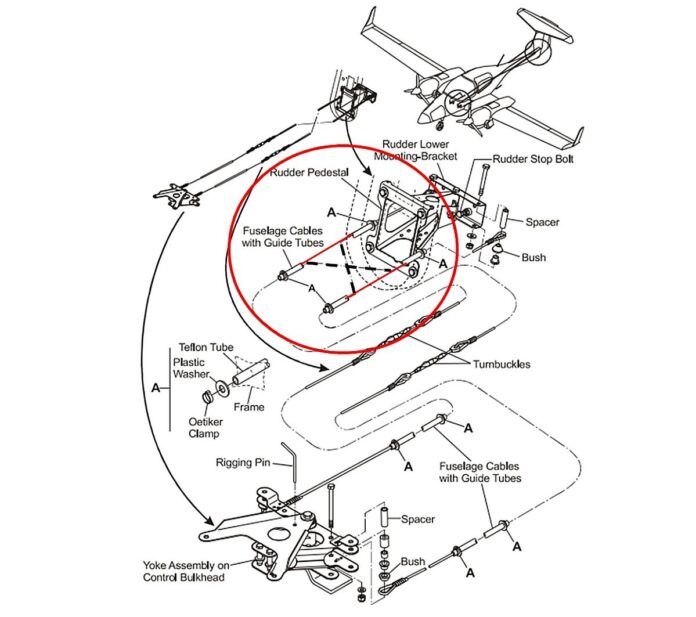

I figured it had something to do with the glider-like S-tubes for the adjustable rudder pedal positioning. manualslib dot com has a diagram in their online DA42 NG manual, page 816, which shows the rudder pedals not included in the image above. The cable routing from the pedals to the yoke assembly shows how the motion gets reversed while maintaining correct motion for L or R pedal inputs. L & R sides can be adjusted independently for length without affecting length or tension from the yoke to the rudder. IT’S IN THE MANUAL.

My flying activities span from (heavy, large, fast and costly) model airplanes, via GA to B747_2/3/400 (retired a long time ago).

Especially the first ones where servo reversal can be done with just one wrongly placed finger touch in the computerized transmitter, I never ever took off without a decent flight control check. Let alone with a newly built or revamped one. Testflying the B747 after heavy maintenance, which I did for a few years, was NEVER done w/o an observer outside, notwithstanding a flight control position indicator in the cockpit.

I still get the shivers from the Convair testflight where the pilots trimmed themselves into the ground because of the reversed elev trim tab.

All along another multi layered Swiss cheese pack. I feel sorry for the apprentice mechanic, he was left in the dark by the system.

Point of Order for those citing checklists:

“FREE and CORRECT” should be checked on the ground, during preflight, well before the engine is running and you are strapped into a place where you likely cannot see the rudder or elevator (or ruddervator or stabilator, etc)

“FREE and CLEAR” should be checked as part of the BEFORE TAKEOFF CHECKLIST to ensure nothing was kicked up into the flight controls, the front seat passenger is well aware of the area to avoid, and that their and your EFB is not interfering with full control deflection.

New to me. Will integrate. Thank you

Happy to be of assistance. This was something I adopted after transitioning from high-wing Cessnas with rear windows to a swaddled-deep Piper where I could not see beyond the wing’s trailing edge after closing everything up and strapping into the seat. Now I do it with any aircraft I plan on taking airborne.

Can’t you just mash down on the rudder pedal all the way and then get out or lean out of the cockpit and observe that the rudder is positioned in the correct direction? And then do the same for the other rudder direction. I have a hard time believing that the rudder returns completely to the neutral position, especially if it is connected to the nose wheel.

The posted picture is lacking in clarity. Although it does show the controls crisscrossing, the picture could show this much more clearly. In the picture, the part above the red circle does show a crisscross as a black cross. It also shows a cross within the red circle, but with two straight red lines connecting the cables incorrectly. Then when you look at the dotted lines, they show connecting the left to the left and the right to the right. It’s easy to be deceived by this picture. The diagram in the maintenance manual should show this much more clearly. Since it has been said that the apprentice technician didn’t have the manual available anyway, then I guess it doesn’t matter.

Smart phone cameras make this easy in many planes, including all Diamond Aircraft.