Remember when the holidays meant a big turkey dinner at Grandma’s? The table would be overflowing with family, friends, mashed potatoes and pumpkin pie. That used to mean about a two- or three-hour drive. Now it means we agonize over when and where we fly. Do we visit my wife’s parents on Thanksgiving or do we go for Christmas? If the guilt factor gets out of hand we might have to do both.

Remember when the holidays meant a big turkey dinner at Grandma’s? The table would be overflowing with family, friends, mashed potatoes and pumpkin pie. That used to mean about a two- or three-hour drive. Now it means we agonize over when and where we fly. Do we visit my wife’s parents on Thanksgiving or do we go for Christmas? If the guilt factor gets out of hand we might have to do both.

Uncle Sam decides for me on occasion. Sometimes we stay home so I can work. My in-laws don’t understand why someone with as much seniority as I have can’t get off every holiday. The families of the guys who are senior to me have the same problem, I suspect. I drew the really short straw this year. I get to work Thanksgiving, Christmas and New Year’s. I guess I’d better start saving for the airline tickets now. Next year’s guilt factor is going to be expensive.

Broken Record

So, this year, it’s going to be you and me. The day before Thanksgiving (TDBT) – yes, I’ve been working for the government too long – is traditionally the busiest flying day of the year. Oh sure, you see that tidbit on the news at 6 o’clock every year, with that junior reporter stuck at the airport – we’re not the only ones who have to work – showing the crowds lined up at the ticket counter. But when controllers refer to the busiest day of the year we’re not talking about the passenger load on the airliners. The number of airline flights is pretty constant and takes up the same amount of airspace – full or empty. What makes it a record day is general aviation.

So, this year, it’s going to be you and me. The day before Thanksgiving (TDBT) – yes, I’ve been working for the government too long – is traditionally the busiest flying day of the year. Oh sure, you see that tidbit on the news at 6 o’clock every year, with that junior reporter stuck at the airport – we’re not the only ones who have to work – showing the crowds lined up at the ticket counter. But when controllers refer to the busiest day of the year we’re not talking about the passenger load on the airliners. The number of airline flights is pretty constant and takes up the same amount of airspace – full or empty. What makes it a record day is general aviation.

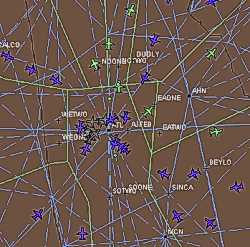

On TDBT, Boeing doesn’t rule, Cessna does – and Piper, Beechcraft, Lear, Mooney, Gulfstream … Anyone who owns an airplane is using it, and it’s a sight to behold. The high-altitude sectors are jammed up with every biz-jet in the country trying to squeeze in between the airliners. The low sectors are filled up with the props trying to work their way around the airline hubs. Every sector at every altitude stratum is crawling with airplanes, and nobody wants to be late for that turkey dinner.

On this day, the supervisors stay out of the way and let the controllers drift toward their preference in sectors. You can lump most Center controllers into two groups: high-altitude specialists and low-altitude specialists. Just in case there are any real old-timers out there, there aren’t formal groups like that in the Centers anymore. We’re required to work all the stratums, from the ground all the way up into the highest flight levels. What I’m talking about are controller preferences. I’m definitely in the low-altitude group.

Oh, the Weather Outside

Starting on TDBT, all controllers will be praying the same schizophrenic prayer: “Please God, make it really, really good weather or really, really bad weather.” It’s not that we don’t want you to be able to go, we just want you to be able to go safely. During the holidays, we know that “get-there-itis” spreads faster than the flu. It’s just bad luck that the holidays coincide with the onslaught of winter weather. Way too many people are tempted to push their personal weather minimums, both VFR and IFR. When they decide to do that at the busiest time of the year, it makes ATC even more interesting than it usually is.

The High Road

Once again, GPS has created a whole new dimension for controllers. Not a day goes by that I don’t work someone who has filed a flight plan into a mountain. Filing direct point-to-point is a lot easier than looking at a maze of airways on a chart, but that chart also has those neat little things like MEAs, MOCAs and MSAs. I know … I know … you’re going to ask for higher when you get a little closer, right? No one files /G with an handheld GPS and we never, ever see anyone whose equipment suffix is listed as /A file airport direct to airport.

Once again, GPS has created a whole new dimension for controllers. Not a day goes by that I don’t work someone who has filed a flight plan into a mountain. Filing direct point-to-point is a lot easier than looking at a maze of airways on a chart, but that chart also has those neat little things like MEAs, MOCAs and MSAs. I know … I know … you’re going to ask for higher when you get a little closer, right? No one files /G with an handheld GPS and we never, ever see anyone whose equipment suffix is listed as /A file airport direct to airport.

Humor me if you will. Purely as an intellectual exercise, can you tell me what altitude you’re going to when the radio quits? I also need to know when you’re going to start that climb. It’s usually an electrical failure that kills the radio and that takes out the transponder too. Remember those old charts with airways on them? The airways had Minimum Enroute Altitudes on them. Remember the intersections that had the “X” on the little flag? We knew what altitude you’d be climbing to back when everyone used those. We had a pretty good idea when you’d start your climb too.

Chilly Willies

That’s the most obvious problem with a point-to-point flight plan in the low altitudes. Slightly more subtle but much more prevalent is icing. It pays to know what is below you when you file your route of flight. That direct route looks real good until you run into icing at 8,000.

That’s the most obvious problem with a point-to-point flight plan in the low altitudes. Slightly more subtle but much more prevalent is icing. It pays to know what is below you when you file your route of flight. That direct route looks real good until you run into icing at 8,000.

“Center, this is N12345, we’re picking up a little light rime, we’d like lower.”

“Cessna 12345 unable lower , minimum IFR altitude in your area is 8,000. Expect lower altitude in 30 miles.”

Just a few dozen miles south he’d have three more altitudes to chose from. The winds are usually much better too.

Mountain Monsters

Speaking of winds, I wish I had a nickel for every time I’ve had this conversation in my career.

“Cessna 12345 are you familiar with the Mt. Mitchell area?”

That’s usually met by a puzzled response. Anybody who is trying to fly over or on the east side of Mt. Mitchell during the winter and spring winds isn’t familiar with the area. The people who know the area know better and avoid it.

“Cessna 12345, the Mt. Mitchell area is 12 o’clock, 30 miles. The area has a long history of severe downdrafts and turbulence. Minimum IFR altitude is 8,700. I’d be glad to vector you around it if you’d like.”

Right now, somewhere in the bowels of the FAA, some legal eagle is having a conniption fit.

Years ago, the MEA on V35 (which passes just east of Mt. Mitchell) was 11,000. Some genius noticed that it exceeded the criteria for 2,000 ft. terrain clearance in mountainous terrain. It did, for good reason. The rules prevailed over common sense and the MEA was lowered to 8,700. So now, at least two or three times a year pilots tempt fate at the wrong time and they get the roller coaster ride of their lives. A 1,000 FPM descent despite applying full power gives you two minutes to ponder your fate. Remember that controller that stuck his neck out and offered you a vector around it? All he can do now (as you tell him of your predicament in a voice two octaves above your normal range) is say “Roger.”

By the way, if you ever find yourself in that predicament, the terrain falls off sharply just east of Mt. Mitchell. That’s not a recommendation. That’s not a suggestion. It’s not even a hint. My only recommendation/suggestion/hint is that you stay away from it when the wind is blowing. However, I have seen a few pilots survive an encounter with Mt. Mitchell by turning due east . If a controller ever offers you a vector out of the way of something (say an airplane, mountain or thunderstorm) you might want to give serious consideration to taking him up on it. Don’t wait until you get scared. By then it may be too late.

The Low Road

Now that I’ve pointed out that flying the low route might be the way to go, let me point out a few problems with that plan. What can I say? Everybody has a talent. Mine is pointing out problems. The first problem is that controllers are reluctant to give away their minimum IFR altitude. Doing so locks up every airport that you pass by. If someone calls for clearance just as you’re approaching the airport, the guy on the ground is going to have to wait. I know you think you’re burning up the sky with that 50-knot headwind, but the guy on the ground waiting for a departure clearance thinks you’re slower in coming than Christmas.

Now that I’ve pointed out that flying the low route might be the way to go, let me point out a few problems with that plan. What can I say? Everybody has a talent. Mine is pointing out problems. The first problem is that controllers are reluctant to give away their minimum IFR altitude. Doing so locks up every airport that you pass by. If someone calls for clearance just as you’re approaching the airport, the guy on the ground is going to have to wait. I know you think you’re burning up the sky with that 50-knot headwind, but the guy on the ground waiting for a departure clearance thinks you’re slower in coming than Christmas.

The next problem with taking the low route is the airline hubs. Let’s take a short mental tour of the Appalachians from the North to the South. Stay just east of the Poconos and you’re in EWR’s backyard. Fly along the Shenandoah Valley and you’re bumping against IAD. There’s just the tiniest sliver of airspace between CLT and the Blue Ridge. Ditto for Atlanta. I can keep you at 4,000 until you get to the northwest corner of CLT’s airspace and then you going to have to go to 5,000. To stay at 4,000 or get down to 3,000 you’re going to have to go across CLT’s final. I’m told all things are possible, but I’ll believe that one when I see it. You might be able to skirt ATL’s northern airspace, but only because their final is running East-West instead of North-South like CLT’s.

I know it looks like wide open skies from the cockpit but when you start looking at it from a controller’s perspective it’s amazing how usable airspace tends to get compressed. Pilots can understand that when they can see the thunderstorms in the summer, but winter brings its own compression factors.

Rough Riders

During your typical inbound push to ATL from the northeast, we normally have the inbounds spread out at FL310, 350, 390. As the interior departures (ATL-bound flights departing inside Atlanta Center airspace) rise up to join the herd from the northeast they tend to get stopped off at FL280, FL260 and (if we get desperate) FL240. We’ll start adjusting the speeds 200 miles from ATL, trying to build five miles in trail (MIT) before we start descending them all to the same altitude where they are fed to Atlanta Approach.

During your typical inbound push to ATL from the northeast, we normally have the inbounds spread out at FL310, 350, 390. As the interior departures (ATL-bound flights departing inside Atlanta Center airspace) rise up to join the herd from the northeast they tend to get stopped off at FL280, FL260 and (if we get desperate) FL240. We’ll start adjusting the speeds 200 miles from ATL, trying to build five miles in trail (MIT) before we start descending them all to the same altitude where they are fed to Atlanta Approach.

Being able to finesse the speeds while the planes are cruising at different altitudes is a real art. Assuming that things are running smoothly, it’s a lot of fun too. Due to the huge volume on that side of ATL, we have the high altitudes split into three stratums instead of the normal two. The lowest, high stratum is FL240-FL290, the middle stratum is FL310-FL330 and the ultra-high stratum is FL350 and above. Can you picture that in your mind? Good. Throw that image in the trash. Today we have moderate turbulence at FL280 and above.

Chopped Liver

Instead of having six altitudes to run the ATL arrivals, we now have two. Instead of having them spread out at various altitudes and being able to finesse the speeds to get five MIT, we take out the meat cleaver and start hacking away with vectors. It’s not pretty and it’s not fun. You’ve got three sectors worth of airplanes compressed down into one and you’re having to make twice as many transmissions trying to keep them all separated.

You’d like to run them a little tighter but it’s hard to do safely with that much volume. You just know as soon as you try, your transmission will be blocked by “how are the rides” for the 20th time in five minutes. (Sorry, that just slipped out.) The next thing you know you’ve got them all slowed down to 250 KTS 300 miles away from Atlanta, the first tiers have been stopped on the ground and the CLT North departures have capped off at FL230 and below. They’ll join all the turboprops (that have been stopped off even lower) in screaming bloody murder because they can’t get up and test out the turbulence for themselves.

So what’s your reward when you walk into the house on Christmas Eve at 11 o’clock? Your wife is sitting by the fireplace with the Christmas tree all aglow. The kids are upstairs pretending to be asleep. As you sit down in your favorite chair and your faithful dog curls up next to your feet the same junior (i.e. clueless) reporter you saw at six o’clock comes on the TV and starts talking about “ATC delays.” Bah, humbug. Merry Christmas indeed.

The Iceman Rings Twice

Let’s go back and talk about icing a little more. Once again, you need to realize the difference in working with an Approach Control and a Center. My Area in Atlanta Center works with seven different Approach Controls. That’s a mighty big piece of airspace. Trying to keep up with what the weather is doing in every section of that much airspace is challenging. Don’t forget that you have to think vertically too. Weather considerations at 5,000 are quite different than at FL310. The controller working you at 5,000 may have just come back from break after working in the flight levels all morning. He’s been working airliners leaving contrails in crystal clear skies all day. Now every time he calls traffic he gets the response, “we’re in the soup.” It’s quite an adjustment to make.

Let’s go back and talk about icing a little more. Once again, you need to realize the difference in working with an Approach Control and a Center. My Area in Atlanta Center works with seven different Approach Controls. That’s a mighty big piece of airspace. Trying to keep up with what the weather is doing in every section of that much airspace is challenging. Don’t forget that you have to think vertically too. Weather considerations at 5,000 are quite different than at FL310. The controller working you at 5,000 may have just come back from break after working in the flight levels all morning. He’s been working airliners leaving contrails in crystal clear skies all day. Now every time he calls traffic he gets the response, “we’re in the soup.” It’s quite an adjustment to make.

Continuing along those same lines, it’s not written down in your flight plan what kind of de-icing equipment you have on your airplane. We know that a Cessna 150 won’t have any and all the airliners will, but there are a lot of airplanes in between that we don’t really know about. One pilot will sound cool as a cucumber reporting light rime and the other will sound like he’s going to hyperventilate. We might be able to guess who has de-icing equipment from that, but you don’t really want us guessing when it comes to icing.

Several times each winter we get into an exchange that goes like this.

“Center, N12345 is picking up some ice we need lower.”

“Cessna 12345 roger, unable lower, traffic 12 o’clock 15 miles opposite direction, a Cherokee at 6,000.”

Thirty seconds later we’ll hear,

“Center, Cessna 345 needs lower the ice is really building up.”

“Cessna 345 roger, traffic is now at 12 o’clock 10 miles expect lower in three minutes.”

Let’s stop and take a close look at what is going on here. The pilot is obviously worried. What is the controller supposed to do? He can’t put the two airplanes into conflict. Five miles doesn’t seem like much until we start looking at the time frame in the context of ice buildup. The average Cessna is going across the ground at about 2 miles per minute. Even if the controller turns the aircraft 90 degrees off course (not an attractive option with a wing-load of ice) that’s 2 and 1/2 minutes before the aircraft clears the airway (or course centerline of the head-on traffic) by five miles. And unless somebody declares an emergency, that controller is going to have five miles or a thousand feet between those two airplanes.

This is the kind of situation for which the term “Pilot in Command” was invented. The controller can’t see the ice building up on your wings. He doesn’t know if you have de-icing equipment, he’s not that familiar with the performance of your aircraft, and he doesn’t know your capabilities as a pilot. If you tell a controller that you need lower or higher due to icing and the controller says “unable,” hopefully he will tell you when to expect the altitude change. If he doesn’t and you need to know, ask. If he says “three minutes” and that is unacceptable, it’s time to come up with an alternate course of action.

Don’t make the controller guess how bad your situation is becoming. Tell him in plain language. Ask him if there is any other available option. If there isn’t and the situation warrants it, it’s time to consider declaring any emergency and telling the controller what you are going to do. Declaring an emergency and leaving an assigned altitude may not be appealing to any of us, but it beats falling out of the sky.

Cheery-Ho-Ho-Ho

By the time you read this, TDBT will have come and gone. The same conditions will prevail through Christmas and on through New Year’s Day, so I hope you’ll find something here useful for your next holiday flight. I hope you’ll take a few extra minutes and carefully prepare yourself to ensure a safe trip. This is supposed to be the season of joy and good cheer. Having your smiling face at the family table is the best way I know to keep it that way.

By the time you read this, TDBT will have come and gone. The same conditions will prevail through Christmas and on through New Year’s Day, so I hope you’ll find something here useful for your next holiday flight. I hope you’ll take a few extra minutes and carefully prepare yourself to ensure a safe trip. This is supposed to be the season of joy and good cheer. Having your smiling face at the family table is the best way I know to keep it that way.

By the way, lest you feel too bad for those controllers who will have to work Christmas, keep in mind that every cloud has a silver lining. When we finally do get home, we get to tell our kids (with a straight face) that we had to work Santa Claus. Just ask any five-year-old: How cool is that?!!!

Have a safe flight!

Don Brown

Facility Safety Representative

National Air Traffic Controllers Association

Atlanta ARTCC