Tehachapi, California: You Gotta Be Dedicated … or a Little Nuts

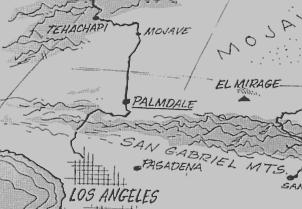

It’s winter, late January. There’s snow on the ground atTehachapi, California. The wind is blowing like crazy. And thetwo of us were about to camp out in an unheated hangar. All ofthis to save money so we could fly sailplanes. The operator ofthe glider school allowed us to park our borrowed tent trailerin the hangar, knowing that we’d be protected from the strongwinds and biting cold. We were appreciative.

It’s winter, late January. There’s snow on the ground atTehachapi, California. The wind is blowing like crazy. And thetwo of us were about to camp out in an unheated hangar. All ofthis to save money so we could fly sailplanes. The operator ofthe glider school allowed us to park our borrowed tent trailerin the hangar, knowing that we’d be protected from the strongwinds and biting cold. We were appreciative.

My buddy, George, brought his own sweetheart of a sailplane, anL-Spatz 55 high performance bird that he’d brought back fromGermany. He was looking forward to trying his craft out on thefamous standing wave that hovers over the Tehachapi Mountainsthat time of year.The rounded lenticular clouds over the ridgesteasingly pointed to the wave.

For my part, I was going along to help crew for him, assailplane flying is not a solo sport. You need help just puttingthe plane together after pulling the fuselage and wings out ofthe trailer. And it helps to have somebody with you duringlaunch to keep wingtips from dragging before forward motion andairflow-lift does the job. But I was also hoping to get someinstruction and earn my own glider rating as an addition to myprivate pilot’s ticket.

We had just a week to get in as much flying as we could andhoped that the weather would cooperate. Indications that firstnight after arrival were not auspicious. We huddled inside ourtent and wrapped up in sleeping bags while playing cards andlistening to a portable radio for some encouragement in theweather reports. Improvement was forecast for late the nextafternoon.

We had just a week to get in as much flying as we could andhoped that the weather would cooperate. Indications that firstnight after arrival were not auspicious. We huddled inside ourtent and wrapped up in sleeping bags while playing cards andlistening to a portable radio for some encouragement in theweather reports. Improvement was forecast for late the nextafternoon.

The next morning we awoke to a stillness and hush that comesafter an evening snowfall. The winds abated during the night,but four or five inches of the white stuff covered everything.The row of tied-down sailplanes on the flightline, threeSchweizer 2-22’s, two 2-32’s and four or five 1-26’s lookederrie under their blankets of snow. George was glad we’d lefthis plane in the covered trailer for the night.

By mid-morning the sun was out and things looked better. Infact, it was really very beautiful with the snow-coveredmountains ringing the valley. The air was cool and crisp. It wasa good day to fly. The lure of the wave excited George, as wehastened to unload and assemble his L-Spatz.

By one o’clock he was airborne, towed aloft behind the supercub. I then sought out the school operator to arrange for my owninstruction and flying. Fortunately, winter activity was slowand there were no other novices seeking guidance. I was the onlystudent for the week.

It took me about four rides with an instructor in the dual-seat2-22 trainer and I was ready to solo. Another four hours ofsolo flying, plus a demonstration flight for my examiner, and Iwas signed off as glider qualified. The only critical part ofthe test was making the spot landing precisely at a place alongthe runway marked by the examiner. No sweat.

It took me about four rides with an instructor in the dual-seat2-22 trainer and I was ready to solo. Another four hours ofsolo flying, plus a demonstration flight for my examiner, and Iwas signed off as glider qualified. The only critical part ofthe test was making the spot landing precisely at a place alongthe runway marked by the examiner. No sweat.

Then I checked out in the single-seat 1-26, which I flew each ofthe remaining three days of our camping and flying vacation atTehachapi. It was terrific, despite nippy morning cold weatherand the return of stiff breezes. The latter pleased George,because it meant return of the wave and he could stay up forhours riding back and forth along that ridge of rising airbouncing off the hills.

For this neophyte it only made landings a little more difficultto judge, for I was not yet qualified to attempt wave flying. Ihad to settle for finding bubbles of rising warm air (thermals)above the south-facing hillsides or over the town of Tehachapi.My flights were considerably shorter than George’s.

For this neophyte it only made landings a little more difficultto judge, for I was not yet qualified to attempt wave flying. Ihad to settle for finding bubbles of rising warm air (thermals)above the south-facing hillsides or over the town of Tehachapi.My flights were considerably shorter than George’s.

I was hooked on the wonderful sport of motorless flight.

Yank Soars Downunder: The Chance of a Lifetime

It was the chance of a lifetime for me, that invitation to attend the instructor pilot school at Gawler, South Australia. It happened during my tour in Viet Nam, the result of conversations with Aussie pilots assigned to our RF-4C outfit.

One evening, while just sitting around the operations center and chewing the fat, the subject of sailplanes came up. I happened to mention that I had flown sailplanes in Arizona and California a few years back. An Aussie pilot began to tell me about the Australian Gliding Federation and their activities. Then he mentioned the annual fortnight-long instructor school and suggested that I ought to go there. In fact, he added, I should take my upcoming rest and recreation (R&R) break to go down there. He’d introduce me to his pals and set things up.

To make a long story short, I was soon at Gawler, some one hundred miles north of Adelaide, and the little airfield devoted to sailplane activities. Its operation is subsidized by the government and makes flying available to citizens at a very modest cost.

My schedule permitted attending only half of the instructor school, but the pilots and ground crews welcomed me with open arms for a marvelous experience. Academics last all morning each day, followed by afternoon flying sessions.

Each night the guys partied. I was not able to keep up with them on that score. In fact, I jokingly told them I’d have to go back to combat in Viet Nam to recover and rest up from the pace they set.

One part of the flying that really intrigued me was the chance to practice landing while on tow. That’s something not commonly taught here in the states, so I was glad for the experience. It’s not all that difficult, but surely a skill that sailplane pilots ought to know.

One part of the flying that really intrigued me was the chance to practice landing while on tow. That’s something not commonly taught here in the states, so I was glad for the experience. It’s not all that difficult, but surely a skill that sailplane pilots ought to know.

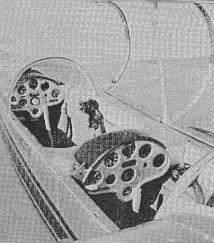

It was also a thrill for me to do that training in the all-metal, high performance Blanik aircraft. Now that’s a real Cadillac. My instructor put me in the front seat and off we went behind a terrific tow plane, a Grumman Ag-Cat. Most tow planes really strain with sailplanes dragging behind them. Not that Ag-Cat. Itgot us aloft in a hurry with no difficulty.

Landing on tow is simply a matter of keeping the tow rope taut,without using excessive drag that would stall the towplane. Behind a smaller craft, like a Piper SuperCub, the sailplane could excessively hamper things.

I loved the handling qualities of that Blanik, especially the hand-operated Fowler flaps for landing. Boy, that is smooth.Sure wish I could have flown that bird more often than theschedule permitted.

I loved the handling qualities of that Blanik, especially the hand-operated Fowler flaps for landing. Boy, that is smooth.Sure wish I could have flown that bird more often than theschedule permitted.

During my stay I managed to fly about four different planes, all but the Blanik single-seaters. It was indeed an experience of a lifetime. I loved every minute and will always be indebted to the gracious hosts of the Gawler and Waikerie sailplane clubs.