A Different Way To Look At IMC

Maybe we’re scaring student pilots too much about what it’s like inside a cloud.

While I am all in favor of a healthy respect for weather among VFR pilots, I also believe there could be excessive fear instilled during the training process that makes an inadvertent encounter with IMC more dangerous than it needs to be.

Having gotten my private-pilot certificate in 1981, I was a VFR-only pilot for about three years before starting work on my instrument rating. My prime motivation was all those flights scrubbed due to a thin cloud layer or just the threat of a narrow patch of weather blocking the way. I had stretched my VFR cross-country envelope with my little Grumman Trainer on trips from my home in New England as far as Key West, Florida, and found myself grounded en route a few too many times for my liking. My dead reckoning VFR navigation and map reading were functional, as far as they went; a necessity in my case, since the Grumman’s factory navigation equipment was limited, to say the least.

I had further motivation when I was hired as an editor at FLYING Magazine in the mid-1980s. Editor-in-Chief Richard Collins was a passionate instrument flyer, and when you worked for him, getting yourself IFR-rated was virtually a foregone conclusion. So, I got my instrument rating, but even so, most of my flying in my own airplane remained VFR-centric. The Grumman’s limited range was as big a factor as the avionics, though I had at least managed to upgrade from the lone Narco Escort 110 in the panel to a King KX170B and a fancy Mode-C transponder. It seems hard to imagine now, but the wonder of GPS navigation was not yet a glimmer in most aircraft owners’ eyes.

From the beginning of my flying lessons, I was always conscious of the ever-present specter of succumbing to “continued VFR into IMC.” As VFR pilots, we were told repeatedly that we would last only a few harrowing moments in the soup before tumbling into irreversible loss of control. I trained and practiced the routine of gingerly executing a shallow 180-degree turn to escape the jaws of death that lurked within the clouds. Even earning the instrument rating didn’t do enough to calm that fear. The training process did not encourage flying in actual IFR conditions, so virtually all of my “experience” at flying on the gauges was under a hood. It was hard to balance the feeling of confidence that was supposed to come from the instrument rating with the ingrown dread of so many years of avoiding clouds as if they were filled with hungry trolls just waiting for me to trespass.

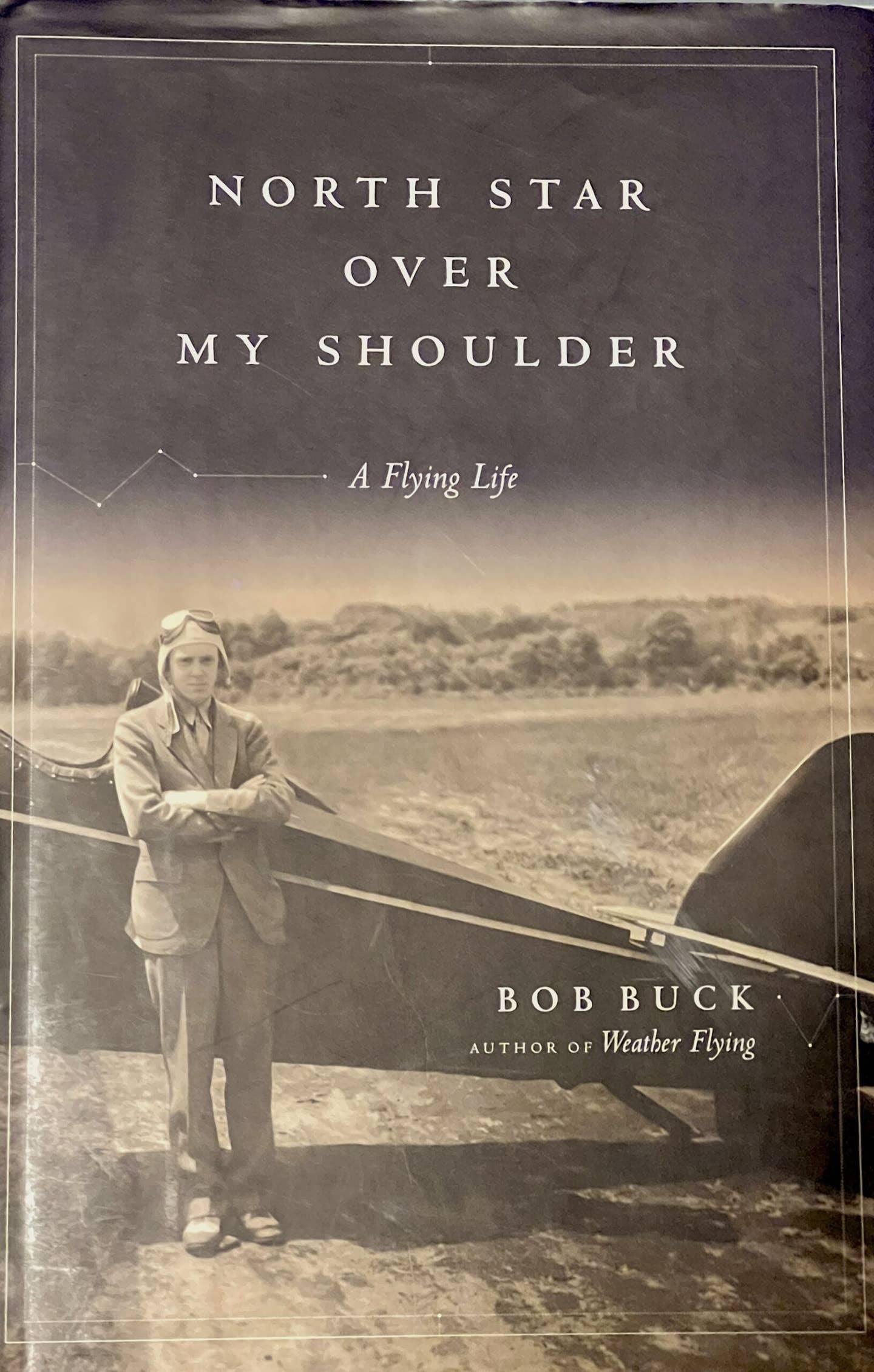

That’s why it was almost a shock to my system when I read career pilot (and accomplished writer on weather flying) Bob Buck’s memoir, North Star Over My Shoulder. He described the first time he flew on instruments—just turn-and-bank, airspeed, and compass—on a 1930 trip from New Jersey to New Hampshire in his Pitcairn Mailwing biplane. And he was a teenager at the time! “At 3,000 feet, I leveled off, pulled the power back to cruise, and dared to look around—there was whiteness everywhere, not a break in it, no ground, no blue sky, just white above, below, all around. But the instruments said we were steady-on, and despite the worry, a feeling of comfort edged its way in. I was well above the ground, not down near trees and hills trying to hedge-hop in bad visibility wondering where the next dangerous obstruction was—no, up here I was safe. I slid back further in the seat and gradually relaxed, felt as though the whiteness was protecting me, that the world now was the snug cockpit and the instruments on the panel that translated how the airplane was doing in space. The airplane and I were released from the earth, not bound to it—we were of the sky only, truly flying.”

Wow. I had never, ever, associated flying in solid cloud with “a feeling of comfort.” Pardon the pun, but it opened my eyes to a new way of looking at flying blind. I thought about Bob Buck’s words the first time I sank into a cloud layer on an instrument approach on my own. He helped reassure me that I was “steady-on.” And while I continue to believe it’s healthy to instill a reasonable fear of cloud into VFR pilots, I wonder if it might not also be a good idea to balance that fear with some of the fascination that Bob Buck experienced on his first instrument flight.