Airplane owners are caretakers, according to the more philosophical among us. Each man leaves his mark on the plane passing through his care before he and machine separate to others, and ultimately, their destinies. Anyone doubting this might consider our present exhibition, an intriguing white Pitts Special most recently named Smokin’ Hot and once again winning the Biplane Gold championship race at Reno last September.

Stock Beginnings

The story begins in 1978 when a young Mike Ryer was awarded a certificate of airworthiness for the Pitts S-1S he had just built in Boulder, Colorado. Ryer constructed his Pitts for strenuous aerobatics in contests and airshows and in 25 years accumulated 3000 hours on the little sportster before slipping away from hardcore acro. There is little written record of Ryer’s time with his stock, red S-1S sport plane, other than an August 27, 1981, mention in The Steamboat Pilot newspaper. Documenting a local airshow with a three-paragraph bit surrounded by huge display ads for mundanely local businesses, The Steamboat Pilot noted, “Mike Ryer flew his high-performance Pitts Special to the delight of audiences…” We bet Ryer got a kick out of it, too.

What is documented is Ryer sold the Pitts to Bob Bryson in 2003. Not a race pilot, but “a big time Experimental builder,” according to later owner Jake Stewart, Bryson was the first to bend the S-1S toward air racing. Not afraid to make notable changes, Bryson’s ambitions stopped short of piloting around pylons, and instead he had pilots J.P. Thibodeau and later Leah Sommer and Mark Barber tend the stick at Reno. During Thibodeau’s time the plane was whimsically Son of Galloping Goat; Sommers and Barber opted for the less cheeky Son of Galloping Ghost. Both names undoubtably played off the P-51 racer Galloping Ghost, iconic for its Cleveland appearances and later coming to huge grief when crashed into the spectator area at Reno in 2011. But that was in the future in Bryson’s day.

Bryson’s modifications included rebuilding, or more accurately, replacing, the wings. Using a Sparcraft kit, Bryson modified the airfoil to his own semi-symmetrical shape using custom-built ribs and clipping the wing assemblies to a seriously short 14 feet 2 inches. No doubt looking for aerodynamic stiffness, he then skinned the wings with carbon fiber, only to quickly remove the wonder material in favor of reapplying fabric covering. The four leading edges were also modified; normally skinned in thin aluminum or molded plywood (the latter stiffer but typically a test of a builder’s skills and patience), Bryson covered his leading edges with Kevlar he had shaped in a mold. He chose the yellow fabric over carbon fiber because Kevlar doesn’t shatter under impact loads (think bird strike) as does carbon fiber.

Additionally, Bryson removed all dihedral from the lower wings, which in turn necessitated longer interplane I-struts.

Wanting to dispense with the draggy, externally braced Pitts tail group, Bryson amputated it in favor of a Knight Twister arrangement. This was a set of all-new vertical and horizontal surfaces built to Knight Twister plans and skinned in carbon fiber. The necessary mounting tabs were welded to the Pitts fuselage to accept the Knight Twister transplant and the result was a big increase in speed.

Bryson also spiced up the engine a bit and was likely the one who replaced the original red paint with white, given that he had changed so much of the little Pitts’ surface area.

Next up was Jake Stewart, who bought the budding hot rod in 2013. Renaming it Bad Mojo, we’re guessing due to its frightening handling characteristics, Stewart continued upping the plane’s performance while adding user friendliness. And by user friendliness we mean Stewart made it so the plane wasn’t trying to continuously kill him. Our mouth sort of went dry when Stewart casually noted he did some engine work, “and I made a new mount to move the engine forward five inches, and it had a 4-inch prop spacer, which I changed to an 8-inch.” Holy aft CG, Batman! That would be fast, but oh so scary.

Asked how it flew with the CG tagging along like the red rag on the end of a load, Stewart gravely intoned, “You did not stall that airplane.” Then a pause, “It would not recover. The Knight Twister tail was too small in area…As I picked up speed it would tail stall in a race if I hit turbulent air and would nose down. And it would not recover until out of turbulent air.”

Bad Mojo indeed.

Summoning an aerodynamicist friend to run the numbers, Stewart enlarged both the horizontal stab and elevator so they were a little larger than the stock Pitts pieces, meaning they cast a noticeably larger shadow than the Knight Twister parts they started out as. This, along with moving the CG from 5 inches outside the rear end of the envelope to the correct zip code, did the trick. Stewart is now able to say the vertical tail is perfect, the rudder maybe a tad larger than it really needs to be and the pitch handling correct. He also opines the Knight Twister tail group dates from the 1930s and simply wasn’t designed for the 220-mph speeds a hot-rodded Pitts runs today.

Winning Power

Besides getting the IO-360 Lycoming properly placed, Stewart gave it a thorough hot-rodding to reach its present state of tune. Pumping up the horsepower is de rigueur in the Biplane class because unlike F1, with its highly restrictive O-200 Continental mandate, Biplane rules allow engine upgrades and the high-drag airframes respond well to it. That makes Biplane a happy place for gearheads looking for some hot-rodding fun but not at the heroic levels associated with the Sport class.

Stewart’s engine mods are underlined by a custom “semi-dry sump” oiling system. This is essentially a remote oil tank concept where oil gravity feeds—there are no scavenge pumps—to a tank mounted low on the firewall and shaped to aid cooling air exit the lower cowl opening. While bereft of any pump-powered crankcase evacuation advantages, namely enhanced piston ring seal and nearly eliminated crankcase windage (oil wrapped around the spinning crankshaft), the semi-dry sump is very simple, inexpensive, lightweight, easy to package and does reduce windage while giving the oil a break from frothing and heating inside the crankcase. Such systems are common in F1 monoplanes, and indeed, the late Jay Jones, an F1 racer from Buena Vista, Colorado, contributed substantially to Stewart’s oiling system.

The remote oil tank also shortens the engine vertically, allowing a tighter lower cowling for better streamlining. This advantage was augmented by building a custom cold-air intake system with 2-inch runners generated with some input from another of Stewart’s friends who just happens to have NASCAR intake design experience. Naturally, Stewart had to build a new cowling to take advantage of the engine’s tighter packaging, which was accomplished with the usual mountain of foam shaped into a plug to make a mold and finally the actual carbon fiber cowling layup.

The engine’s exact compression ratio is a team secret neither current owner Sam Swift nor Jake Stewart want to divulge, but Stewart said enough when he allowed the Lycoming has “extremely high compression north of 12:1. We’d go through about two starters a year!” That’s definitely a racy amount of squeeze, sufficient to move the engine into the accelerated overhaul timetable typical of specialized race engines. But that’s not really a factor as the plane doesn’t accrue too many hours a year, just the once-a-year racing plus enough time for the pilot to remain current.

Because of the increased rpm—3100 rpm while racing is typical—the camshaft specifications were changed to suit. This was done by slightly tweaking a Phase 3 Ly-Con camshaft. Ignition is provided by one magneto and a single Light Speed Engineering Plasma III system.

An engine this highly tuned would be a candidate for four-into-one headers, but Stewart specifically designed a custom two-into-one crossover exhaust because such systems tend to make more torque than long-tube headers in his experience. This also avoided a long, large-diameter, aerodynamically draggy tailpipe.

In what may be a Biplane class exclusive, the white Pitts runs something of a tunnel cowl exit built by Bryson. Stewart thought to expand on this and try an exhaust augmented cooling exit. He fitted a stainless steel heat shield, but as an expedient shot the aluminum rivets he had on hand instead of stainless rivets. During the test flight the aluminum rivets failed due to the heat—goes to show you what sort of forces are in exhaust—and the hot gas burned through the fuselage skin. This literally heated Stewart’s seat cushion and, “I made the fastest trip ever back to Denton, Texas.” The heat was bad enough, but the real danger was chemical. “I was feeling dizzy, and that cockpit has only a tiny vent. I put two fingers through it to scoop as much air as possible. You can’t open the canopy because it comes completely off…I lost three days of work to carbon monoxide poisoning.” The augmented cooling was abandoned.

Swift Going

In 2022 Jake Stewart sold Bad Mojo to fellow Biplane competitor Sam Swift. It was time for a change, says Stewart. “I don’t know. The racing just isn’t what it used to be. I won in 2021…it was more stressful than fun; the juice wasn’t worth the squeeze. I’ve got two kids now…and I had to burn up all my vacation to go to Reno. [If I race] I can’t take the kids to Florida or Galveston. I just wasn’t enjoying it as much.”

Meanwhile Sam Swift, who interestingly enough was flying another ex-Jake Stewart Pitts, a red S-1D, was wanting to speed up his racing program. Swift’s red ride featured light hot-rodding, but was well behind Stewart’s white racer when it came to speed mods. Knowing that buying an already hot-rodded airplane was easily a less expensive and labor-saving method of going fast than modifying the one he already owned, Swift kept after Stewart to sell him the white plane.

As Swift put it, “You’re time and money ahead to buy an existing race plane than modify your own. You can work yourself up [through the racing ranks] by buying and selling airplanes.” It’s a strategy Swift has been faithful to, having started racing in 2016 in the red Pitts he had bought from Stewart. But the last several years Swift seemed stuck in fourth in the Biplane Gold race. “I couldn’t crack the podium.” Hence the move to the white Pitts.

And it worked. Mounted in the ex-Bad Mojo (now Smokin’ Hot), Swift had the Biplane field covered last year and he took the Gold win at 206 mph. This was Swift’s first Biplane championship and the airplane’s third as it took the Gold in 2014 and ’21, both with Stewart, plus the 2022 win with Swift at the stick.

Swift made no modifications to the plane in the short time he owned it prior to his 2022 win, so his plans are simply to “get more comfy with the airplane” and tease out “how to operate it most efficiently for racing.” He has no plans for major airframe mods. “That’s why I bought a different airplane…I’d have to spend thousands to gain the mods I did,” so expect to recognize Smokin’ Hot at the races for some time. Swift does plan on upgrading to a JPI 830 engine monitor while completely stripping out the existing instrument panel and rewiring the plane. His goal is to make Smokin’ Hot’s panel mimic his old Smokin’ Hot’s panel (see the naming sidebar) as he liked its layout and says it will be easy to duplicate.

His other plans are to freshen the engine, or at least some cylinder work, and build a lighter weight carbon fiber cowling, plus possibly try a different propeller—information the rest of the Biplane field didn’t want to hear, we’re sure.

So, if old Pitts never die but just go faster, it’s a good bet Smokin’ Hot will eventually have more owners in its future, along with more stories to tell.

Photos: Tom Wilson.

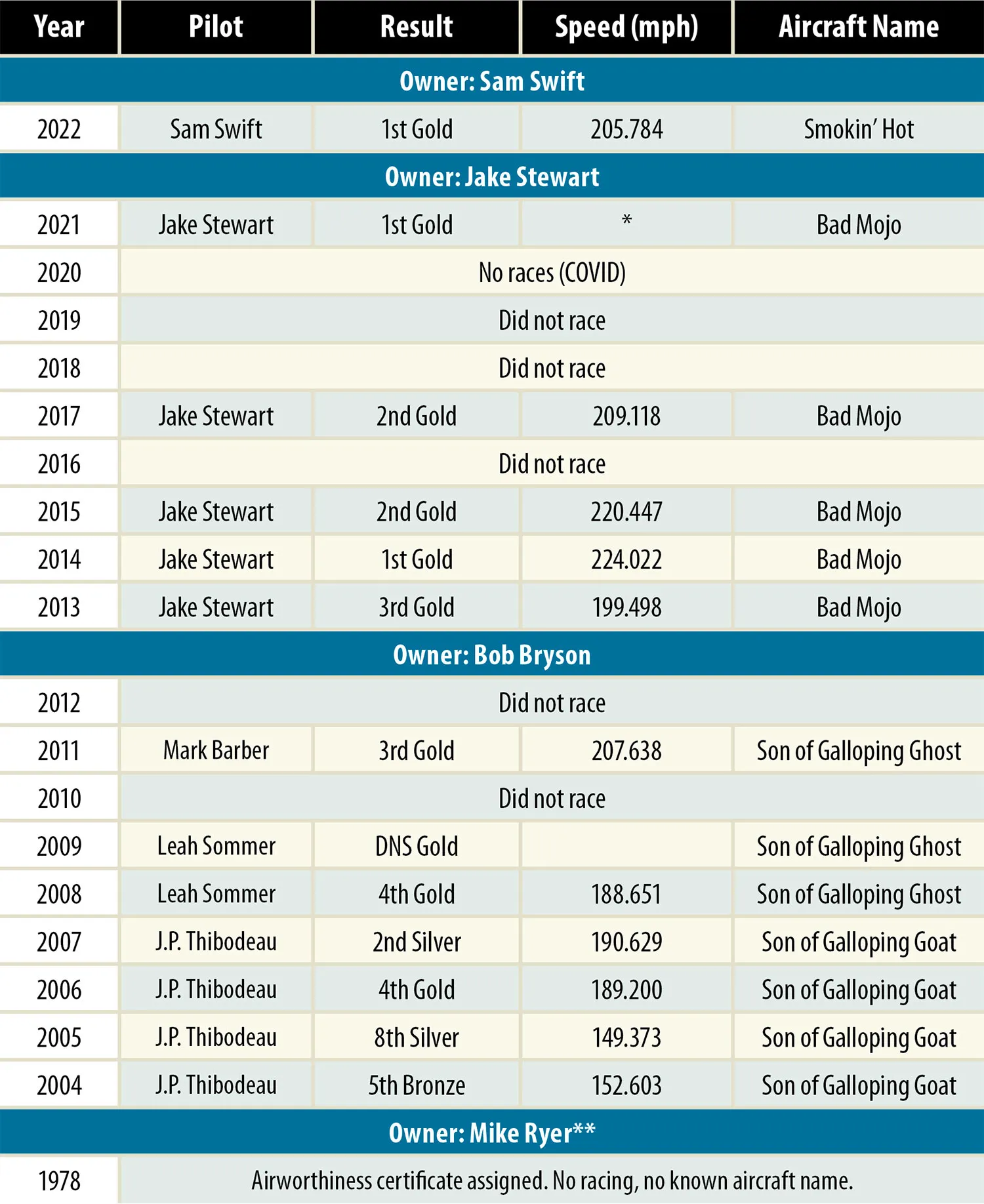

Racy Record

Spanning 18 years, four owners, five pilots and four names, our feature airplane’s record includes winning the Biplane Gold championship a commendable three times. This is more notable considering its career is concurrent with the all-conquering Tom Aberle/Andrew Buehler Phantom with its 13 Biplane Gold wins.

**For more Mike Ryer see: Changing a Perfectly Good Airplane, October 2017 and November 2017.

Playing The Name Game

In the sort of thing driving historians to strong drink, there have been two racing Pitts Specials named Smokin’ Hot. Even more confusing, both planes have been owned by both Jake Stewart and Sam Swift, and both planes were painted red, at least for a portion of their lives.

First off, the name Smokin’ Hot references Sam Swift’s wife, Paula, and as he has a penchant for naming his race planes alike, we think Mr. Swift a smart manager of his marital capital. The original Smokin’ Hot was a red Pitts S-LHN registered N2968G and was first owned and raced by Jake Stewart as Zipper II with Race Number 3 before selling it to Swift. When Swift bought and first raced this plane in 2016, he renamed it Smokin’ Hot and kept Race Number 3. This plane was sold by Swift in 2022 and the Smokin’ Hot name and Race Number 3 transferred to the white Pitts featured in the main text of this story.

The white Pitts featured here, N11PJ, was originally red as noted in the main text, but was resprayed white many years ago. It’s also gone through a series of names as listed in the “Racy Record” sidebar above, but it was Bad Mojo carrying Race Number 10 and Maltese crosses from 2013–2021 so it’s been well-known by that moniker in modern times.

Of course, Swift had to have some fun with all this. Not wanting to alert his Biplane competitors that he was going to show up for the 2022 races with the fastest biplane currently running, he kept the sale of his original red Number 3 Smokin’ Hot quiet. He then registered for the races with Smokin’ Hot, a Pitts Special carrying Race 3, and everyone logically thought he was returning with his usual plane, until they got to Reno.

This article originally appeared in the June 2023 issue of KITPLANES.

For more great content like this, subscribe to KITPLANES!

Quite a history in such a relatively short time for this aircraft. One can only imagine the sheer expense of getting this ship to this point.

Looks a little harder to land than the Champ I’ve been flying 😉

I am having a hard enough of a time to just be a rental pilot. I cannot imagine how much it would be to be A, an owner, and B, to hot rod said aircraft.