You remember the bicycles hanging under the wing, right? You may not remember that the yellow-and-red high wing carrying those bikes was the Murphy Radical prototype, even though it was on our cover way back in the October 2017 issue of KITPLANES. But everyone seems to remember the bikes. Well, no bikes this time, but we’re taking another look at the Radical because much has happened at Murphy Aircraft in the last six years—and even since we last checked in with the company. (See Jerry Folkerts’ “Murphy Resurgent” story in the June 2022 issue.) And now we have the Radical nearing volume kit production this summer.

Murphy’s Moves

It wasn’t long after our 2017 visit to Murphy that founder Daryl Murphy retired. An entrepreneurial sort who had penned multiple aircraft and by then had seen his company through 30 years of kit manufacturing, Murphy was ready for a change and so was the company. The model line had grown confusingly, with some designs cannibalizing sales from the others. While there were real winners in the Murphy lineup it was time to put all the good ideas in fewer airframes and concentrate on business. Those airframes are the manly sized Moose, the right-sized Radical plus the affordable Rebel.

Putting the oomph behind that concentration was Daryl Murphy’s sale of his company to Chinese conglomerate Duofu International Holding Group. As we’ve seen with other aviation companies under Chinese ownership—namely Cirrus, Continental and Superior—the offshore management has taken a long-term view of Murphy’s business and has no intention of moving the company from its rugged British Columbia roots. While providing capital and some oversight, Duofu has left those on the ground in Chilliwack to run the company.

Today Murphy Aircraft is guided by CEO Jensen Li with Doug Thorpe managing sales and marketing. The vibe in the shop right now is admittedly sleepy as management put kit production on hold in favor of updating not only their offerings but also the manufacturing process. However, meaningful groundwork is being laid toward firing up the production lines later in 2023 when the reworked Radical kit hits the market. Murphy’s intention is to make its kits easier to build with far more predrilling and improved supporting materials.

Big pluses for Murphy are that after 35 years and more than 2000 kits sold, the company has both a built-in fan base as well as generous shop space under the roof in Chilliwack. That facility includes a production-level laser cutter and an imposing 2000-ton press capable of squeezing any conceivable bit of aluminum into an airframe part. Welding and other production capabilities are in place at Chilliwack so the hardware to make volume kit production a reality is not a problem.

Hit The Books

An issue has been documentation. The builder’s manuals were all very 1980s with super-thick three-ring binders and tons of text but few images. These don’t provide the level of customer support expected today, so updating the build manuals based on SolidWorks files is underway. Bringing the Radical into the computer age is a real boon to builders who will be able to manipulate 3D drawings of assemblies and work with proper parts lists while not wading through a forest of paper.

As for the kit hardware, the initiative is for Murphy to complete more steps for the builder. Until now, Murphy kits were marked by formed aluminum channels, stampings and flat sheets of aluminum, some of it predrilled in spots—but much of it not. Compared to the match-drilled excellence from other aluminum airframers, the Murphy kits were perhaps at times closer to scratch building than riveting together a modern quickbuild kit. A quality build was possible, but it asked for a big chunk of the builder’s time and the opportunities to make—and correct—little mistakes were too frequent.

Assisting Murphy Aircraft is Marco Probst, owner of the white Radical we’re featuring in this article along with a Moose under construction. His hands-on experience building a Radical as a customer gives Murphy one source of accurate feedback on how the kit works once it leaves the factory, plus he has incorporated a few of his own updates that Murphy can evaluate as well.

The first Murphy airframe to get the update treatment is the Radical, starting with the tail kit. Where the original kit arrived at the builder’s door mainly as a pile of formed aluminum, the new kit is completely predrilled. In fact, Murphy’s goal—not completely finalized at our visit—was to ship major components such as the vertical and horizontal stabilizers Clecoed together so the builder could simply start pulling rivets. This is not an issue in Canada where there is a “51% rule” but professional building is legal and widespread. (Murphy assembles many of their Canadian customers’ airframes in-house.) But what the FAA would allow was still to be determined last fall. No matter the outcome for U.S.-bound kits, the upgraded parts will go together faster than Murphy’s previous offerings.

Speeding assembly is sort of building on a Murphy tradition. The company is fond of pulled rivets—the only solid rivets in a Radical are in the wing spar—so while there are many rivets, they pull quickly by one person armed with a pneumatic gun. And then there is that 2000-ton press stamping out whole bulkheads, ribs and other complex shapes. Building a Murphy airframe is becoming more of an assembly rather than a fabrication process, lending credence to the company’s 1000-hour build-time estimate.

The Radical

With Murphy Aircraft living the outdoor life in British Columbia it’s no surprise they offer rugged, metal utility aircraft built to take the weather, carry a load and think nothing of banging around on rocky river sandbars or brush-thick fields. The Radical packages this ethos in an ample two-seat airframe ready to haul nearly 1000 pounds of fuel, people and gear. Plus the kids on an optional rear bench seat stolen from a Jeep Wrangler. The result is not just native STOL utility, but pleasant handling, excellent stability and a general all-around friendliness endearing to the enthusiast pilot.

The Radical’s mostly metal construction includes an aluminum monocoque fuselage with wings created from a built-up, strut-braced aluminum spar and stamped ribs covered with aluminum skins. The horizontal stabilizers are also strut reinforced for reduced weight. Control surfaces—ailerons, flaps, elevators and rudder—are framed by aluminum stampings and fabric-covered, also to save weight. Control actuation is pushrod for the ailerons and elevators, cable for the rudder. Pitch trim is electric.

As mentioned, pulled rivets are used throughout, save for solid rivets in the wing spar—it’s built up from a series of doublers joined with approximately 600 solid rivets. This requires the builder to have a large gun or squeezer that is otherwise unneeded, plus the time to do the work. Alternatively, Murphy will build the spar for $2000 in their special rivet machine. This saves the builder about 30 hours plus buying another tool and results in a tight, well-built spar, explaining why most customers opt for the service. For the remaining pull rivets, Murphy helps the builder by sticking to a small range of rivet sizes so the builder needs only one size of rivet puller.

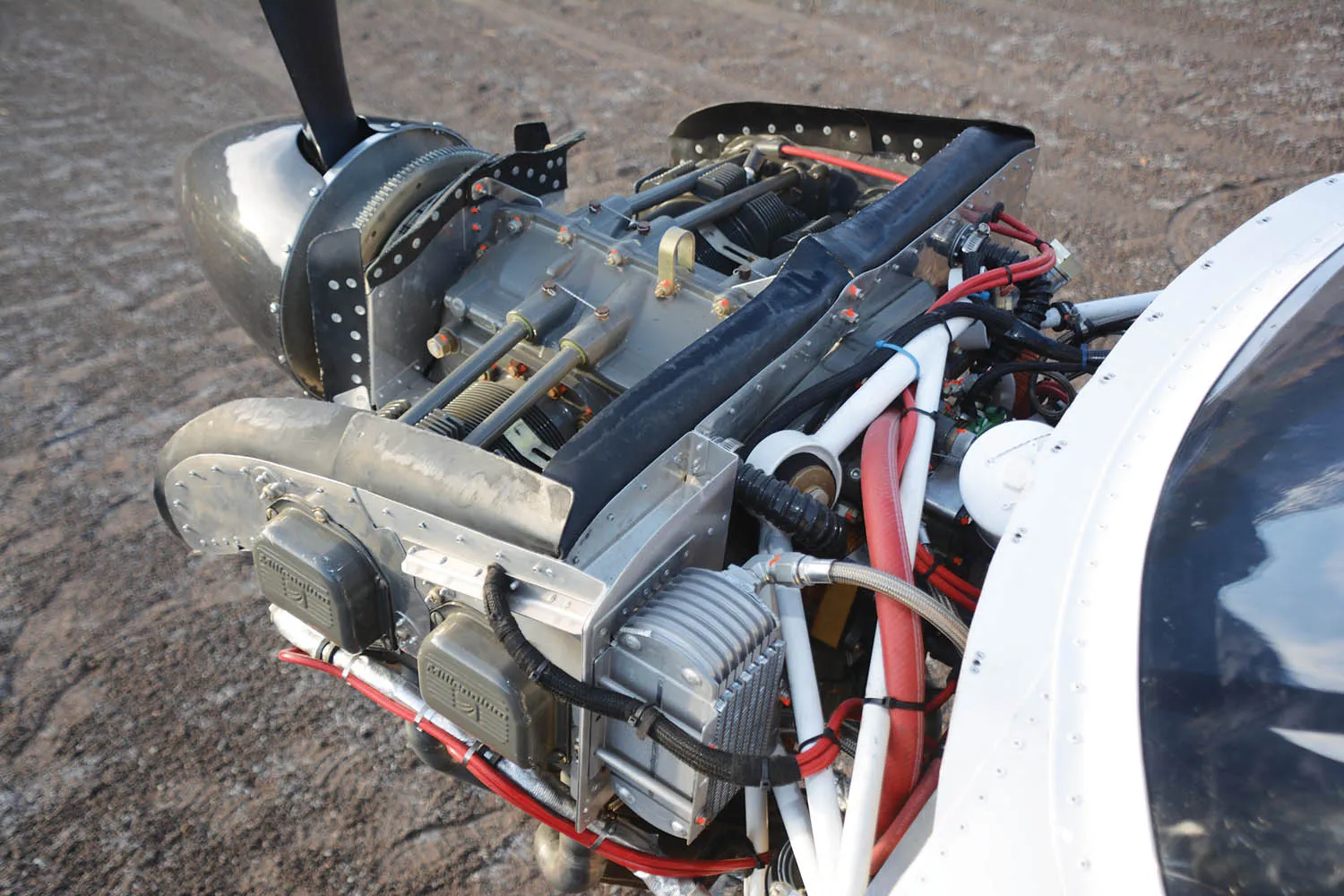

Fiberglass wing and stabilizer tips are standard, but the cowling to fit the standard O-360 Lycoming engine was just beginning development at our press time. It’s likely the Murphy cowl will use a nose bowl, with top and bottom halves made of a combination of aluminum and fiberglass, but this hasn’t been confirmed. In any case, Marco built the cowling seen in the photos by starting with a Rebel/Elite cowling, which shares the same size firewall. It splits horizontally, with the top aluminum and the bottom fiberglass.

Wheel Fun

Murphy has traditionally built its own wheels and brakes, saying this was less expensive than buying off-the-shelf units, but that philosophy is fading. A cost-benefit analysis was planned, so we might see familiar brand rolling stock when the Radical kit hits full production. Furthermore, while the supplied tire is a sizable 22×8.00, many Radical owners will step up to big Alaskan Bushwheels. Since the standard single-piston Murphy brake isn’t up to stopping the 31-inch Bushwheel tires and doesn’t mate with the required wheel, alternatives will have to be found.

While seating isn’t a hot topic in the typical kit build, Murphy has been positioning the Radical as a 2+2, meaning it’s designed to seat two adults comfortably in front and accommodate children or crowd short-term adults in the rear bench. Think of it as a plus-size two- seater. The kit’s front seats are simple one-piece fiberglass buckets as sold to the off-road truck market, mounted on sliding adjusters to aid ingress/egress, along with access to the rear seat or cargo area. Turns out the compact back seat of a Jeep Wrangler works fine for the Radical’s second row, so Murphy was mulling the possibilities of supplying that assembly or something similar.

Engine and propeller choices are left to the builder, but the Radical is designed around the parallel-valve 180-hp O-360 Lycoming, with the 220-hp Lycoming IO-390 the suggested optional, plus-power choice. Given that the cowls are likely to be different between the O-360 and the IO-390, we’d expect the smaller engine to be supported first.

Marco’s Prototype 1.5

Our first look at the Radical in 2017 was via the prototype airframe powered by an IO-370 Titan swinging a fixed-pitch Catto prop. The airplane sported a Garmin G3X Touch panel. It wore oval rear quarter windows, had no rear seat and used bungee landing gear taking up what the 22-inch Goodyears weren’t interested in. Since 2017, Murphy has sold five Radical kits—Marco’s all-white machine is the first customer-built example to take flight. However, you can also consider it prototype 1.5 as Murphy management is still finalizing the kit being updated for later 2023 release and is carefully eyeing the details Marco built into his plane. Conveniently, Marco lives over just a few gorgeous ridges of the Coast Range in Squamish, British Columbia, so both he and his plane are regulars at Murphy’s Chilliwack headquarters. While not a Murphy employee, Marco is definitely a good friend of the family and is contracted to help update the Radical build manual.

Wanting to build on the Radical’s low-frills personality, Marco gave his build the muscle and specialized hardware needed, but didn’t expend any weight or money on anything not required. That means carbureted O-360 power, a long, paddle-like Catto fixed-pitch prop, vortex generators on the wings, squared-off rear quarter windows, Acme Aero oleo gear (instead of bungees), floatation tires and a cargo door on the left side. Otherwise the airframe is stock Radical. Thanks to a modest equipment package and lack of interior upholstery and sound deadening, Marco’s Radical weighs just 1120 pounds empty.

Radical Flying

Walking up to the Radical it comes off as just a little larger than you thought. Much of that is the generous 36-foot wingspan propped up on 31-inch tires—tall guys appreciate the little extra height under the wing. Thanks to the large, single-piece, upward-hinged doors being completely out of the way when opened against the bottom of the wing, getting yourself or gear in the Radical is a wide-open task. Tall people need to slide the front seat all the way aft before entering or risk an awkwardly stiff moment getting their feet around the control stick. Once in, there is truly generous room for two big adults; there’s no need to rub shoulders, only to scoot the seat forward to reach the rudder pedals and assume a flying position. Legroom is unquestionably large and headroom is open as well. With no spar carry-through and a reasonably tall cabin there’s no sense of having your head up inside the wing roots.

Visibility is excellent for front seaters for other reasons, too. Above all, the four-cylinder engine means a short cowling, so even with the passenger seat mounted a little lower and more reclined than the pilot’s seat in Marco’s machine, at 6-foot-2 I could see over the cowling in the three-point when relaxed in the low seat. With a slight effort to sit up and out from the seatback—to mimic the pilot’s seat position—the view forward was panoramic. There’s no requirement for the low copilot’s seat in Marco’s airplane, he just has it that way—so builders can put the seats where it suits them best and have fine flying and taxiing visibility.

Light aircraft seating is always less than luxurious, but the Radical’s basic one-piece fiberglass buckets give decent support and should wear well for the long cross-country ahead. The three-point seat belts are basic, non-reeling triangles taking a minute to adjust the first time, but like the fixed, one-piece seats save both money and, most importantly, weight.

Enough Talk, Let’s Fly

Starting and run-up are normal carbureted Lycoming. The fuel gauges are coffee-urn sight tubes and the glass panel needs minimal adjustment so that’s all quick. If anything is different, the lack of rpm drop during the E-Mag check might get your attention. Taxiing is normal, even on the somewhat soft tires (Marco had plenty of air in his Bushwheels, 15 psi, the day we flew) and shock absorber gear. As with most eager-lifting airplanes, the takeoff is a cinch because the ground roll is over about as quickly as it starts given a notch of flaps. Start by feeding in the power and immediately adding forward stick. The tail comes up before the power is all the way in. Count one, two and pull back modestly as the Radical is already off the ground. It really wants to fly.

Climb can be steep if you want, for sure. There aren’t any FAA-spec 50-foot trees in Canada so we didn’t attempt any rocket launches from right off the deck. Besides, Marco had already demonstrated steep departures for the camera, so we already knew it gets out steeply enough.

Our test flight came at the end of the day, and what had started as full 44 gallon standard fuel tanks was down to a bit under half tanks after earlier cross-country and photo flights. But with the two of us we had around 450 pounds of humans on board, plus Marco’s seabag of survival gear, so we were at least 650 pounds—let’s say two-thirds of the way—into the Radical’s impressive useful load.

From sea level, 80 mph worked well for the initial climb, giving 1000 fpm. Passing through 3600 feet with cruise power we noted a stabilized 800 fpm at 75 mph indicated, all with normal deck angles. Leveling off you come across the Radical’s only performance quirk, a 100 mph-indicated cruise speed. Leisurely cross-country pace is something many serious STOL birds share, what with their big-tire dress code and fulsome high-lift wings. Factor in the Radical’s nice size—it’s no compact Kitfox or RANS—and there’s no getting around it’s draggy. Considering the numbers turned in by the larger but more powerful Moose, Marco guesstimates a pumped-up Radical with a 220-hp IO-390 running 65% power to a constant-speed prop and likely smaller tires could return as much as a 130-mph cruise. But in his practically equipped plane at real-world fuel burns 100 mph is it.

It is, at least, an enjoyable cruise. The Radical delivers rock-solid stability, pleasing and well-harmonized control forces and little need for attention in level flight. It really does just about fly itself, with only an occasional correcting pressure needed. Marco hasn’t bothered with an autopilot and none is needed as the point is to go flying anyway. You won’t be shooting an ILS as a matter of course and the piloting workload is inherently low, leaving plenty of brain cells to soak up the scenery or think about the big fish you’ll catch from the boat you’re carrying.

It’s worth emphasizing the Radical’s just-right control forces. If you’re used to the thumb-and-finger delicacy of the RV series you’ll find the Radical’s stick inputs a definite notch stiffer. If you’ve been herding a Cessna 180 lately you’ll think the Radical is a sports car. To us, the slight weight in the stick, coupled with the plane’s faithful tracking, were perfect for taking the workload out of getting there, while landing and maneuvering forces were pleasantly light and responsive. We liked it instantly.

Slow flight and landing are what really count in a STOL plane, of course, and here the Radical is perfectly at home. Slow flight hovers—now there’s a word for you—around 47 mph indicated given 1500 rpm and 16 inches of manifold pressure. Stick forces go up just enough to notice but are easily relieved by two nudges of the elevator trim switch atop the stick if you want. Marco never bothers with retrimming, saying the stick forces never get that heavy, and we agree unless you’re planning on dragging banners or something. Control response remains solid at sub-50-mph speeds, allowing moderately aggressive maneuvering if needed.

You’ll have to work at stalling the Radical. Clean and power-off, it starts hunting and mushing downward between 300 to 600 fpm—still with some roll control—beginning in the 40-mph range. You’d have to stand it up on the tail to get a power-off break. More practically, we got a distinct break at 43 mph when carrying 1600 rpm, 16 inches and no flaps, or a similarly callable but still benign break at 39 mph with full flaps. It dropped the left wing a few degrees each time but this was easily picked up by the rudder, or rudder and aileron as the latter stayed at least partially effective into the stall. Recovery was rapid, around 50 feet.

Marco’s airplane even had a built- in stall warning: The horizontal tail would give a single, audible clunk as a panel back there oil-canned right at the break. The takeaway was you’d have to really try to stall a Radical in any normal scenario and the recovery was as fast as letting off the stick.

Interestingly, the Radical doesn’t have huge, or even hugely effective, flaps because it doesn’t need them thanks to its native handling and good lift in the low speeds. Instead, the flaps give the expected pitch and speed effects rather than suddenly changing the plane’s personality. The short flap handle on the overhead is the one control with heft to it, coupled with a meaningful over-center effect as you swing it down or up. It would take a combination of technique and muscle to get an imperceptible flap actuation if you didn’t want the passengers to notice. But that’s not the point when swooping through the trees to a full stop on a sandbar and, like us, we noticed Marco didn’t bother finessing the flap actuation, either. Just give the handle a firm handshake squeeze to free the deep detent, then a quick swing through its short stroke. You’ll get an aerodynamic bump as the flaps rapidly go in or out, but you’re already on to other things.

By the time it comes to land you’re already expecting a cakewalk and you get it. Keeping speed up to 70 mph around the pattern saves time and works fine because the Radical sheds speed like a parachute. Steep descents or dragging it in both work well, visibility over the short cowling is good and the final approach is easily done at helicopter-like speeds as you aim for the touchdown point. Come over the fence at 50 mph, round out for a short beat, then it settles while you pull the stick back a surprisingly long way. You have the needed elevator authority and a nice long stick travel to easily gauge the pitch input. Keep pulling to hold the sight picture over the top of the cowl and the Radical keeps slowing before lightly plopping on the rocks and weeds.

Directional control on the deck is pleasantly on the job with quick little rudder inputs until you slow, and then you’ll stretch your jeans to reach all the rudder pedal travel. This is no short-pedal-travel airplane. It feels like your feet move a foot by the end. Hard braking works—the binders aren’t dangerously over-effective given the tall tires and slippery meadow surfaces—and it comes to a halt with little drama. I got it stopped 400 feet from the threshold on my first attempt using a normal approach and moderate braking on rocks and weeds. Practice would definitely help. At his best, Marco did the deed in 290 feet immediately prior to my landing. Fun!

Radical Building

If the Radical fills its niche handsomely, what remains is Murphy Aircraft delivering on the updated Radical kit this summer. Certainly their plans to deliver well-documented, completed-as-possible kits has Murphy pointed in the right direction. It’s worth remembering there is currently no fast-build alternative from Murphy (other than having them build the kit for you for non-U.S.-registered aircraft). Murphy is considering a fast-build kit option in the future, but that’s ahead of our story right now.

Today’s standard kit is close to a quickbuild thanks to its many formed parts and pulled-rivet construction. Thus, a complete firewall-back Radical kit is $44,516 in U.S. dollars (this might change after the kit updating is finalized) and using numbers Dave Thorpe was working up for a prospective customer during our visit we can estimate (also in U.S. dollars) $48,000 for an O-360. Add $800 for interior, lighting and rear seat, budget $20,000 for avionics and another $20,000 for exterior paint. That rounds out to $133,300 before you add a propeller.

The Takeaway

As the off-airport movement continues Murphy’s Radical certainly has its bona fides covered. The handling, carrying capacity, short-field performance and apparent durability of the airplane is certainly a draw, while the updated kit promises a low-angst, fast build and quality features. The Lycoming power is as mainstream as it gets and after 35 years, albeit with an ownership change, we think Murphy will be around for customer support. It comes down to STOL performance and how much you want to carry versus the builder’s cross-country expectations. And oh yeah, you can still get the underwing bicycle racks.

For more information: Call 604-792-5855 or visit www.murphyair.com.

Manufacturing Murphys

Murphy already has a well-established physical plant in Chilliwack, so their recent upgrades can’t be seen on the shop floor but will be apparent to future builders in the form of better build manuals and more completely finished kits. Another invisible improvement seems to be a willingness to pay ahead by having kits in stock awaiting orders. The Radical, for example, is expected to have a five-airplane batch built in late 2023.

The Hiscocks Connection

After sampling the Radical’s pleasant handling and high-lift personality we became curious about its airfoil. Which led to Murphy Aircraft’s earlier association with celebrated Canadian designer Richard Duncan Hiscocks. Born in 1914 in Toronto, Hiscocks quickly became a respected aeronautical engineer, moving to De Havilland Aircraft in England during WW-II, along with being sent to study German aviation engineering in the summer of 1945. Returning to Canada and De Havilland Canada, Hiscocks designed the wing of the immortal Beaver using an airfoil of his own calculation and rose to chief designer at DHC in 1949. He also contributed to the Otter, Caribou, Buffalo and Twin Otter while at DHC before working with Canada’s National Research Council.

Moving west to British Columbia, from 1990 to 1995 Hiscocks worked with Murphy Aircraft on aerodynamic design and stress analysis for the Rebel and Super Rebel/Yukon and his influence seems to be living on in the Moose and Radical.

Murphy Radical

- Kit Price: $44,500

- Estimated completed price $140,000

- Estimated build time 1000 hrs

- Number flying (at press time) 2

(4 others under construction) - Powerplant Lycoming O-360

- Propeller Catto 84×43 fixed-pitch

- Powerplant options IO-390, Titan 370

AIRFRAME

- Wingspan 36 ft

- Wing loading 11.66 lb/sq ft

- Fuel capacity 44 gal (59 opt)

- Maximum gross weight 2100 lb

- Typical empty weight 1120 lb

- Typical useful load 980 lb

- Full-fuel payload 716 lb

- Seating capacity 2+2

- Cabin width 44 in

- Baggage capacity 270 lb

PERFORMANCE

- Cruise speed 100 mph

- Maximum rate of climb (2100 lb) 1000 fpm @ 75 mph

- Stall speed (landing configuration) 39 mph

- Stall speed (clean) 43 mph

- Takeoff distance 400 ft

- Landing distance 300 ft

Specifications and pricing provided by the manufacturer.

This article originally appeared in the April 2023 issue of KITPLANES.

For more great content like this, subscribe to KITPLANES!

I stopped reading when I got to the “Chinese ownership”, part.

Yup. Are they buying companies to extract the IP and build their own cheap copy?

Same here.

“White Radical”? Hahaha!

I remember back in the day that building an experimental was a low-cost way into owing your own aircraft. Seems that today, “low-cost” is about $150,000…or more. The cost of reliable powerplants is outrageous, as is materials to build the thing. That relegates most folks without the necessary funds to Legacy LSA’s like C120’s or Ercoupes. Yes, you’re in the air, but in a rather limited way and can enjoy all the issues that come along with a 70 year old machine that leaves the ground. Flying has never been cheap, but in this modern day the costs of getting “up there” tend to dissuade all but the most dedicated pilots.