Research Shows Dangerous And Costly Turbulence Is On The Increase

Fasten your seat belts. According to the National Business Aviation Association (NBAA), changing weather patterns and shifting jet streams mean the next few decades are going to make flying bumpier….

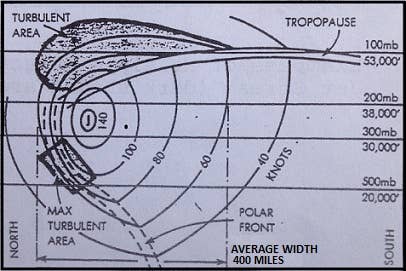

Image: National Weather Service

Fasten your seat belts. According to the National Business Aviation Association (NBAA), changing weather patterns and shifting jet streams mean the next few decades are going to make flying bumpier. Already much more prevalent than it was in the 1970s, turbulence is on the increase, and research shows it is likely to continue to get stronger.

The NBAA reports that “a June 2023 research project published by the University of Reading and the American Geophysical Union revealed significant increases in clear air turbulence (CAT) over the past 40 years, an ominous indication of what’s likely to come in the future.”

Study co-author Dr. Paul Williams noted the largest increases came over the United States and the North Atlantic, with a 55 percent increase in severe-or-greater CAT in 2020 compared to 1979. “Following a decade of research showing that climate change will increase clear-air turbulence in the future, we now have evidence suggesting that the increase has already begun,” he said.

And the discomfort is likely to extend past passengers’ and pilots’ backsides and on to their wallets. According to Williams, increased turbulence “not only poses added risk of physical injury to cabin crew and passengers, but also increased operational costs and more emissions as the aviation industry works to reduce its carbon footprint.” Williams cited a 2007 study that revealed “up to two-thirds of commercial flights [within the survey window] had deviated from the most fuel-efficient altitude because of turbulence, with an average duration of 41 minutes.”

He also cited the potential for costly increases in scheduled inspections due to airframe stress—and disincentives for paying customers. “Passengers already uneasy about flying may become more unnerved by even mild encounters with turbulence,” he said.

NBAA suggests that operators use improved turbulence-detection resources available through the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA) Aviation Weather Center (AWC) and the National Weather Service to help steer clear of the most serious turbulence. Jennifer Stroozas, warning-coordination meteorologist for NOAA’s AWC, told NBAA, “We’ve made tremendous advances over just the past few years, thanks to improved weather forecast models with more data going into [them] and better understanding of the science in these models. That results in better forecast information across the board, including when evaluating the potential for turbulent conditions.”