Some time ago, I wrote about what happens during an emergency in the tower. But wait. There’s more. Of course, few pilots have declared an emergency, and even fewer have actually had an incident or accident. Crashing an airplane is on nobody’s bucket list (I hope), however the probability of surviving a plane crash varies with the type of crash. If your gear collapses, you’ll probably survive. If you hit something while VFR in IMC, well, you might make the news. For the most part, the FAA has developed some pretty good response actions to assist pilots in need, and not just during an actual no-guano emergency.

Who Ya Gonna Call?

The number of people who find out about your distress starts with the controller you tell. From there it spreads to the whole room, which then spreads to a couple other rooms of people. Depending on location, the resources ATC has in place to assist in an emergency are good. Of course, if you are out in the middle of nowhere and start to have problems it’s best to let ATC know well before hand so they can monitor and send help.

I spoke to a few pilots lately just to ask them questions like, “What would you do if X happens and Y fails?” It was a small crowd, but half the room didn’t even plan to tell ATC. Of that half, 90 percent of them said they would not be on flight following, “just squawking 1200.” They believed their chances were higher by concentrating on flying the airplane and trying to get down safe. Getting down safe is one thing, but what about when you’re on the ground with your airplane in pieces, in hostile weather far from … anything?

Whether pilots believe talking to ATC is important or not is a big deal when handling an emergency that could potentially turn from incident to accident. Altitude can buy you time, but ATC can increase your chances. When a pilot squawks 7700, 7600, or 7500, lots of things happen behind the scenes and people all the way up to DC could learn of your plight. Crash statistics show that someone on the ground knowing what’s happening increases your chance of survival by decreasing response time.

For this discussion, we can say that statistically, the probability that something catastrophic will happen is very low. Nonetheless, anything could happen at any time. Want proof? A wing fell off a Piper Arrow at Daytona Beach a couple years ago. So, yes, “stuff” happens. Despite that sad day, ATC and other aircraft provided a quick location for authorities.

First Response

The first thing ATC listens for is the magic words “declare” or “emergency,” or even an ELT in some cases. Of course, I’ve also heard expletive-laced exclamations that were sufficiently informative that I declared for them. The controller in charge (CIC) and other controllers in the room are generally notified by the controller shouting, “I’ve got an emergency!” This normally ceases non-relevant conversation. The controller working can’t just stop everyone in the air, so he or she starts to move everyone out of the way and continues working the emergency, asking for fuel and souls on board, etc. Any information a pilot could pass is useful.

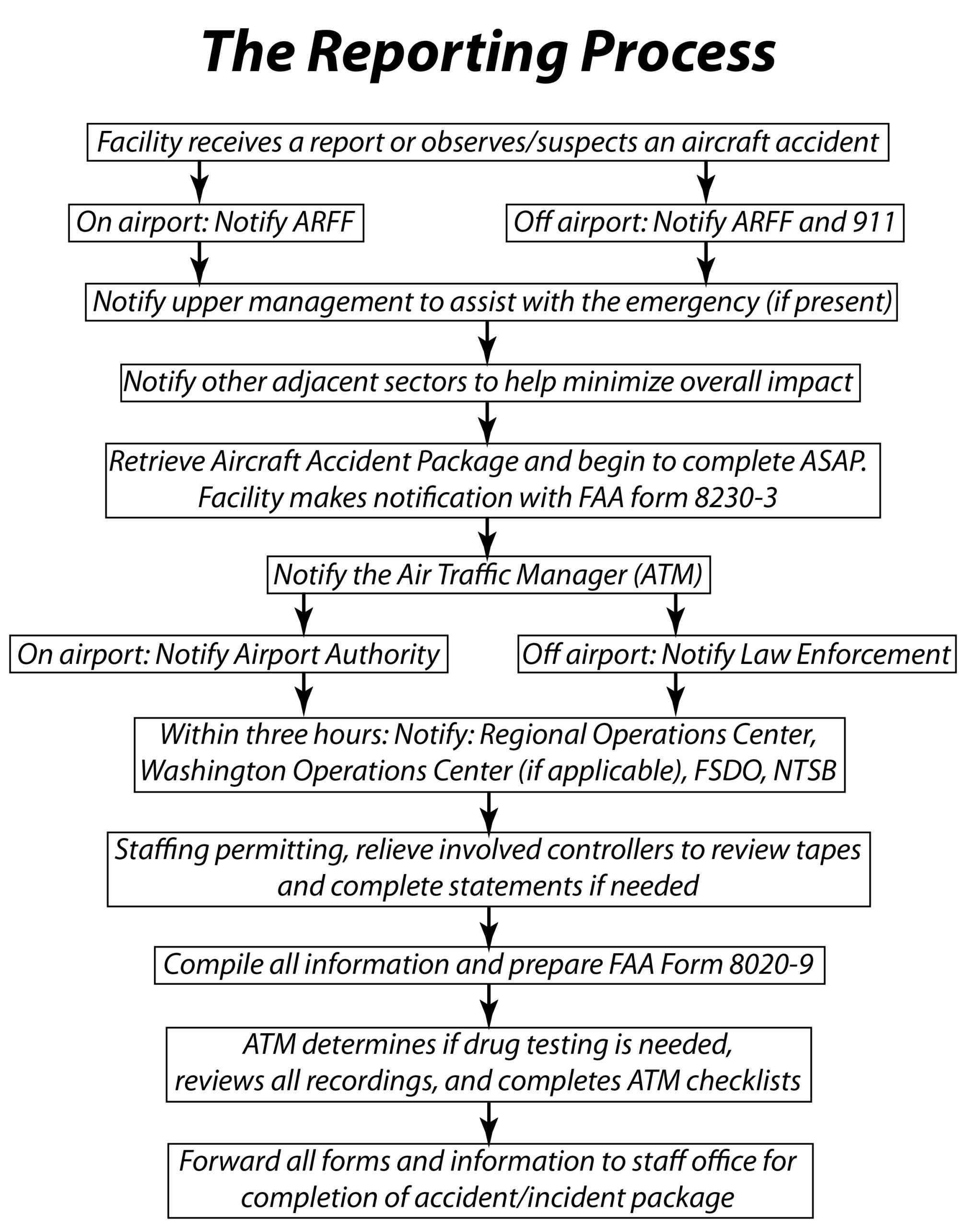

Someone in the facility is responsible for the crash phone and will gather information and “roll the trucks” as soon as practical. The CIC then notifies management, whether they are in the building or at home, and calls for any assistance needed from other controllers on break or otherwise occupied. Adjacent facilities (including approach control) are notified by the first controller to get to it. It’s a team effort, and emergencies are time-critical. Better that two people call than someone thinking “I thought the other controller called people.” The CIC then breaks out all the forms potentially needed and starts filling ’em out.

Now assuming all goes well and the aircraft lands safely, this process slows way down. A “non-event” is an emergency that has a good outcome (aircraft lands safely and no one is hurt and nothing is damaged). We still have paperwork to do, but not nearly as much as a worst-case scenario.

Once an emergency starts, the controllers working are generally not relieved until the event is over. However (if staffing permits) another controller will come to monitor the position. It’s great to have a second pair of eyes in a higher-workload, higher-stress environment. If an accident does occur, controllers can be held for drug testing and removed from their position for a certain time. This is not disciplinary; it’s just standard procedure.

There are between one and 20 forms that should be filled out. The number varies by facility type, airspace, what aircraft/vehicle is involved, etc. These are all incident forms that need to be filled out ASAP while fresh in everyone’s mind. They have all the details on them including weather observations, recent PIREPs, traffic workload, etc. It may seem like a lot of unnecessary info, but if bad goes to worse, these little details go into the investigations by NTSB and help determine what went wrong and the best way to move forward.

Secondary Crash Phone

All that initial flurry of activity is complete. Now what? We’re going to assume that you declared but didn’t make it to the airport. It varies by exactly where you declare, but if near an airport that has “Aircraft Rescue and Firefighting” (ARFF), the Tower is notified to ring the crash phone. If you are out in the middle of nowhere, the approach control or the ARTCC you’re talking to will run their checklist similar to above, and those will alert higher authorities. It starts with ARFF (if applicable) then moves out to the closest rescue station. If there are none, it goes to the ARTCC Ops desk and they get in touch with Search and Rescue (sometimes a Civil Air Patrol airplane) to dispatch immediately.

Keep in mind that safety comes first. If it’s bad weather, they won’t send another aircraft out to find a downed one; initial efforts would be ground-based only. After all is done with search and rescue, the Regional Operations Center (ROC) is notified. This adds exponential resources to assist if needed. The ROC works with many other entities such as NTSB and FSDO, who are at the top of the notification list immediately. After that, the original CIC or supervisor then notifies the Domestic Events Network (DEN).

The DEN is an interagency teleconferencing system that allows certain agencies to communicate and coordinate their response to violations of restricted airspace. It was established just after 9/11 in response to the attacks.

To break it down, it’s basically an open line that any ATC facility and a few other agencies can call and use to coordinate/communicate things happening across the country in real time. One thing that will put facilities on the line is if someone squawks 7500. Not only would my radar make a loud buzzing noise, they would hear it all the way up in DC. If ATC determines it’s real, the closest fighters will be airborne.

The DEN is also used for certain VIP movement. So, from beginning with one controller who heard the pilot say something, within 10-15 minutes, up to 50 people know about an emergency. If that emergency turns into an accident, that number goes up to the hundreds. FSDO and NTSB are at the top of that list because if the worst happens, they need to be first on scene right behind fire/rescue. Immediately after an accident or crash is when most critical evidence is present.

After the DEN is notified, the CIC, Supervisor, or Air Traffic Manager (ATM) continues along the list with law enforcement or a military authority if needed. Then the list goes to the ATM and supervisors of the facility if they weren’t in the building. Next, the local ATC union president is notified. It may seem redundant, but the first thing management does is notify up their chain of command, and sometimes repeat the calls that should have already been made by the CIC or first person in charge. It’s similar to when an accident happens and everyone calls 911 for the same thing.

If the crash happened on or near the airport, the airport operations supervisor is notified, who then notifies airport authority and manager. Finally, if needed, the ATM will notify the Washington Ops Center. That call typically isn’t made unless another 9/11 or anything involving Air Force 1 happens.

Final Outcome

As you can see, there are significant resources for not just emergencies, but accidents. Walking away alive is a variable highly determined by the actions of the pilot before the crash. Of course, I am a firm believer in aviate, navigate, communicate. However, I also believe that “communicate” part is a must and should be included as soon as possible. This is also why I highly encourage filing IFR whenever possible, or at least utilizing flight following—you’ll always have someone to talk to.

In addition to your standard required ELT, tying your GPS to your ELT (or having an ELT with embedded GPS) will greatly assist in locating you, whether it is a personal beacon or installed in the aircraft. Sure, those things can be pricey, but any pilot knows that flying is not cheap. You might spend $100K on an airplane; would you up that to $101K to increase your chances of being found if the worst happened? It’s clear that the sooner someone knows about your distress, the sooner help will arrive.

My goal here is to change the minds of some pilots who don’t talk to ATC at all or are not very helpful with exchanging information. Since most professional pilots are flying on IFR flight plans, talking to ATC is not an issue. Where does that leave the rest of us? You aren’t taught “aviate, navigate, communicate” just to throw the last part out. Help us help you. Talk to us. You might even find that most of us are friendly and helpful.

Response Failure?

In an emergency, they say that seconds could mean the difference between life and death. It doesn’t matter if it’s an airplane crash or just a bicycle crash. The logic is that the sooner help arrives, the higher are the chances of surviving any accident. Think of the Titanic for example…

I was talking to a buddy from a facility in Louisiana a while back, and we started talking about a Cessna that had crashed. He wasn’t working that day, but he told me what happened. A Cessna was on VFR Flight Following passing from west to east at 3500 feet. In most cases, Approach or ARTCC talks to airplanes just passing by, but in this limited scenario, they shipped the Cessna to a nearby tower (Class D below 2700). The pilot called the tower and told them he was just passing by, and they approved the transition. Minutes later, the Cessna starting having some kind of problem and went down.

The tower controllers never saw it as they were focused on their airspace. In this tower, all aircraft that call the tower have their call signs written down on paper to assist as a memory aid for the controllers. This controller wrote it down, but took several minutes to get back to it. By the time they did, the Cessna was down. They assumed he went back to Approach, but didn’t see anything on the radar, so nothing was thought of it. Then 15 minutes later, Approach called and asked if the Cessna had landed there. They responded, “Negative. We thought he went back to Approach and continued.” The approach controller responded, “He never came back and we don’t see him on radar.”

After another five minutes of scrambling to figure out where this airplane had gone, the tower supervisor looked up the call sign on FlightAware and saw its flight track descend to the ground near their airspace. With all the back and forth the emergency checklist was long delayed. It was a whopping 15 minutes after they realized the aircraft was missing.

The occupants of the Cessna did not survive to the time emergency responders arrived. They both made it out of the plane but perished. The facilities involved got a report from responders stating the pilots could have been saved if help had arrived earlier. All said and done, several facilities have been going through some audits to assess response time statistics and prevent this from happening again.

From the description I heard, I’d surmise there was a failure on several parts. In this case, the pilot never told ATC there was a problem and the controllers forgot about him. Why was this aircraft switched to a tower well below his altitude? Did Tower feel that since the airplane was not in their airspace, they were not responsible? Why did it take over 20 minutes to send out help? There are so many questions that arise here.

I’m very interested in reading the final NTSB report. Lives were lost due to lack of communication and positive control. If the pilot had simply made just one transmission to ATC saying, “Mayday,” or “Oh, crap,” or something, ATC definitely would have gotten the hint and those people might be alive today. —EH

This article originally appeared in the July 2021 issue of IFR magazine.

For more great content like this, subscribe to IFR!

I’ve declared emergency 3 times in my 20 years in the pt135 business. Twice as pic with smoke in cabin and once as sic with flap failure. Never once did I get asked to file a report even though the trucks were rolled. Of course my chief pilot handled reports to the POI. All three times the flight ended without bent metal or anyone getting hurt. I have even asked on two occasions to have the fire trucks stand by when refueling a medical flight due to the large medical O2 tanks in the airplane. I guess the moral to the story is don’t be afraid to ask for help, it could be a lifesaver.

There is actually even more going on if there is a crash. I’m not sure if it is still called FAA Airways Facilities, because I get weird looks when I say I worked there, but they are also notified in Washington, and the local technicians facilities were all recertification as operating correctly by a different tech than the one that originally certified the system (radar, ILS, VOR, runway lights, tapes were pulled, communication checked. Pretty much anything the pilot might have relied on for that operation where the plane crashed. (I did both the certification, then became the maintenance manager that did the call outs for recertification of the systems after a crash)

I had to leave that position once I figured out pilots were being blamed for crashes that I knew were actually caused by something else, and I was being ordered by my upper management to withhold the information from the NTSB. It was a case of me knowing too much. Having been a pilot, controller, and airway systems specialist in all areas (navigation, communication, radar, and weather equipment) I knew all aspects of what was going on in each area… and I didn’t like what I was seeing or reading in the NTSB reports.

Over the last 45 years I’ve had my share of fire trucks following me down the runway, for everything from gear, engine, and structural issues. (I flew a lot of old crummy planes) If you are out over the water the Coast Guard is put on alert. That was good to know on a few occasions.

I did find it a bit embarrassing, because I always felt like it was my fault. What didn’t I look at close enough before the flight. But, then again, how are you going to know when a brake line is going to start leaking fluid, or a gear indication micro switch will stop working, or an engine gasket will fail, or bearings will fail? I always would dig to find what went wrong, and and tried to figure out… could it be prevented from happening again?

That has always been my thought process in every aspect of my involvement in aviation, What happened and can this be prevented in the future.

As strange as it seems, some pilots hesitate to declare an emergency because they fear red tape and bureaucracy. As a controller for 40 years, I have worked my share of emergencies, from a rough-running engine to an off-field landing, and NONE required a pilot to fill out paperwork. The process is deliberately made simple in order to encourage pilots to declare when they have an issue, and not worry about paperwork. There may be a FSDO investigation later if there are injuries or substantial damage, but the local tower or radar room isn’t involved. Don’t hesitate, if you need resources, there is only one way to get them. Talk.

They are confused about priorities for life.

In the fall of ’78 I had picked up a CAP T-41 just out of overhaul at Montgomery AFB and was taking it back to Oklahoma City. As lead in a 2-ship with another CAP bird, we were cruising along at 8,500′ when mine swallowed an exhaust valve. I can attest to “oh crap” (or a close approximation thereof) as being approved language because ZMEM never blinked an eye. After chatting with the controller, it turned out that the nearest facility with equipment and hard surface was NAS Meridian, Ms. The engine tolerated 1,500 rpm well enough that landing was assured and the bird was towed off the runway to the ramp with no problems. The Navy rescue troops were disappointed, they had their Huey spun up but didn’t get to fly that day. Instead, we opened up the cowling, pulled a plug on each cylinder, confirmed #4 had no compression, and walked over to the flight line cafe. I was simply given a yellow pad, a pen, and asked to write up my debrief while I waited on #2 to find a mechanic and drive over from Meridian Regional airport in town. You would think that landing on an active military facility would spark all kinds of formalities (it probably does today), but there was a time in our world where outcome was more important than process. Of course, if I’d just shown up without talking to anyone, I’m sure things would have been different.

The moral of the story is to communicate with the folks that can help you. With more than one brain working the problem, you have a better chance for options that might be missed.

In over 50 years now, I don’t believe I’ve ever met or talked to any ATC people that weren’t kind, courteous, and glad to be of assistance. They’re great folks doing great jobs and are there to keep us all safe. They want to help and won’t throw you in jail for an occasional utterance of “Aw’ s@%t, Memphis I got a problem”.

Thank you for such a great article,

I spent some time with an FAA investigator. He told me to declare an emergency any time things are not normal which could include deviating to an alternate with a sick passenger. When things are not normal , the pilot has more distractions and possible stress and is more likely to make a mistake like descending to the wrong altitude. If the pilot has declared an emergency then most things that go wrong after that declaration: the pilot is off the hook for violations and the FAA examiner does not have to investigate the violation because the pilot was in an emergency event and that covers it. Basically he told me to please declare an emergency when things go wrong or are not normal. ATC was always my friend.

I remember one flight where I had fire warnings on both engines within a few minutes of each other. They were not on fire but we did have to land. I asked ATC to give me vectors to the nearest airport that could accommodate my plane with more than 6000 feet of runway. I didn’t even have to figure out which airport or where to go land. They made the decisions for me. I remember once being low on fuel on top of fog. I asked ATC for the best airport they had within 150 miles rather than me trying to figure it out while my fuel got lower. Basically every place had fog. ATC was always my friend.

Thank you to all the controllers that watched over my flights.

Two calls, one a Part 135 cargo flight with low oil pressure on the right, uneventful landing at destination. Cleared into busy Class B (then TCA), given runway choice, the tower asked for fuel, cargo, souls and as we touched down the fire brigade followed us up to the ramp. No paperwork.

The second, years later, in a single, which I had spent several hours practicing emergency procedures a week before, recently 40 hrs out of overhaul cracked an intake manifold at altitude. I was talking to APP(VFR-FF) when the engine ran rough, lost 15 kts and the engine stumbled as soon as I touched the throttle. I reported the problem, describing the engine roughness as a “uniform” roughness. They asked if I was declaring an emergency, and I said, not at the moment, but I might and I was going to land somewhere, soon; where’s the closest airport? They declared the emergency (didn’t tell me), offered some suggestions, one of which was my base, an unpaved short strip, and one much closer with a big long paved runway and a maintenance shop on field. The questions: able to hold altitude, fuel, full less 20 minutes at 7500 ft, souls on board and asked me to call them once I was on the ground. I landed uneventfully. The engine stopped on short final when I pulled the throttle, and we had just enough energy to roll out and up onto a parallel taxiway out of the way. I had to find the number for Approach and was calling them when everyone showed up lights flashing looking for the plane crash. I finished my ATC call let them know everything was fine, and the aircraft was secured, then addressed the sheriff, police and EMTs. It was described as a precautionary landing and I never heard another word from anyone. Didn’t even make the local papers. If there had been a crash I would have been very happy for their presence. Good landing: walk away. Better Landing: airplane flies again.

I replaced the 121.5 MHz elt with a 406 MHz. About a year after I put it in, after a heavy rainstorm the remote failed in the dampness. I got a call from SAR on my cell phone about that ELT. They knew exactly where on the ramp the airplane was within about 20 feet. The FBO was able to turn the ELT off and fix it. This stuff does work, and works well. I now carry a PLB when I’m in the back country…just in case.

Reminds me of the day circa 1980 when I was dozing off on a DC-8 YVR-YOW.

When I woke up passenger across the aisle said I missed the excitement.

Crew said they were diverting to YUL because of weather.

But passenger said they had shut down an engine, he flew the airplane frequently and knew its sounds.

Firetrucks were beside the runway on touchdown at YUL.

Deplaning down stairs at the front door I observed cowling of engine 2 open and an open case of cans of oil on the tarmac.

In the terminal, some pax had called their office in Ottawa, were told weather was fine there.

Obvious why the crew diverted to Montreal – more maintenance capability there.

Why do crews lie to pax?

While I was very familiar with airliners and maintenance, and the nearby passenger familiar with how the airplane sounds, I expect a few other pax got very suspicious – a well-known oil company’s name on box and cans, and engine open.

I have declared an emergency twice in 38 years of flying GA. Both times was met by crash trucks and both times they were not needed. A third emergency happened to me when I had an in-flight cockpit fire and I did not have time to declare an emergency – I was too busy trying to land before I died in a flaming ball of aluminum/magnesium alloy.

I managed to land on the runway at an uncontrolled airport and was met by another pilot with two large fire extinguishers who had seen me trailing black smoke. They had little effect (magnesium is extremely hard to extinguish once burning), but fortunately he had called the local fire department, who came with a pumper truck and extinguished what was left of the airplane. Note that an in-flight cockpit fire is fatal 50% of the time, and causes injuries another 25% of the time. The chances of escaping with no injuries is the other 25%. I had no serious injuries (smoke inhalation and singed hair on my arm). These stats courtesy of the NTSB reports at the time of my incident.

BTW, the two emergencies were while in IMC – a retractable gear failure when the electrical system failed (pumped the gear down, but had no gear indication lights), and a surging engine (carb ice that did not clear so I opted to land and check it out).